Cathryn Gathercole

As we left this engrossing exhibition at the British Library my friend said: “there is nothing new under the sun”.

The things which were not new in this case – patterns of political influence, exercise of power, the language of diplomacy and the impact of dominant narratives – are repeated throughout history and across continents.

This exhibition charts the period from the 5th century when groups of Saxons, Angles and Jutes came over the North Sea and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms emerged, up to 1066, by which stage the now united and wealthy kingdom of England was conquered by Duke William in the Norman conquest.

Impressive texts

Unsurprisingly (it is the British Library after all!) these stories are told through an impressive collection of original texts.

The manuscripts highlight the dominant influences: Celtic patterns from Ireland and Iona, illuminated gospel-books reflecting Roman connections and the spread of Latin literacy alongside Christianity.

It was King Alfred and his successors from the 800s who set in motion the political unification of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons.

Alfred was an advocate of the English language and during his reign he sought to achieve parity between written English and Latin, apparently out of a desire to make knowledge accessible to a wider population.

It isn’t too big a leap to see in these exhortations the early idea of nationhood and Englishness which has continued to this day, serving different political masters and different political ends.

It also occurred to me that giving a layer of the population access to knowledge, and valuing the language they spoke, would have won him valuable allies in the unification process, enabling him to become the first king and ruler of all the Anglo-Saxons.

Inevitably, the artefacts which remain are those of the elite. History is written by the victors after all, and the victors are usually male and rich.

There are some clues as to the role of women, including examples of powerful women owning property and wielding significant influence in their own right. It was more often the lot of noble women to be married off to cement political alliances.

Emma of Normandy was married to two kings, and was mother to two more. She commissioned a biography called ‘In praise of Queen Emma’ which unsurprisingly portrayed her in a flattering light. This would be more impressive if a second copy hadn’t been discovered recently giving a different ending.

The idea of changing and editing texts came up surprisingly often in the exhibits. Translating from one language to another led to changes in nuance, reflecting changing morals and contemporary thinking.

Highlights

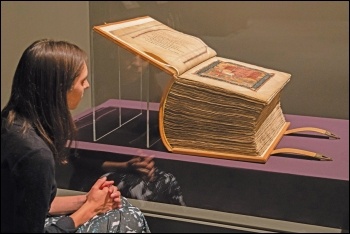

One of the highlights of the exhibition is the Codex Amiatinus – the only remaining copy of three huge bibles made.

The story goes that one copy was being taken from Wearmouth-Jarrow to Rome as a gift, but unfortunately Ceolfrith who was taking it, died en route.

The dedication page was scraped and Ceolfrith’s name was replaced by another – a forgery not discovered until 1888. It seems not even the victors have their own way all the time.

- Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War is open at the British Library in London until 19 February. See bl.uk/events/anglo-saxon-kingdoms for details