Review: Pale Rider

The Spanish Flu of 1918 and how it “fanned the flames of revolt”

Hannah Sell, Socialist Party general secretary

Laura Spinney’s book on the 1918 flu pandemic was first published in 2017. Now in the midst of a new global pandemic it is being widely read.

Spinney gives a global and vivid account of the huge effects of what was probably the biggest pandemic in history. Yet, as she explains, in popular history it is remembered mainly as an adjunct to the World War One.

It is estimated, however, that one-in-three people on the planet became ill and somewhere between 50 and 100 million people died, compared to 17 million who died in the carnage of World War One.

In Britain, the war was the bigger killer, but there was still a gigantic 224,000 who died from the flu, and between the two events almost a million lives were wiped out.

War and revolution

As Spinney makes clear, while the pandemic was a major event in world history in its own right, it cannot be separated from the war and revolution that surrounded it.

Even its name, ‘Spanish flu’, came about not as a result of its origin – which was certainly not Spain – but the fact that Spain’s neutrality meant that the pandemic was reported in the press there, unlike in the censored warring countries.

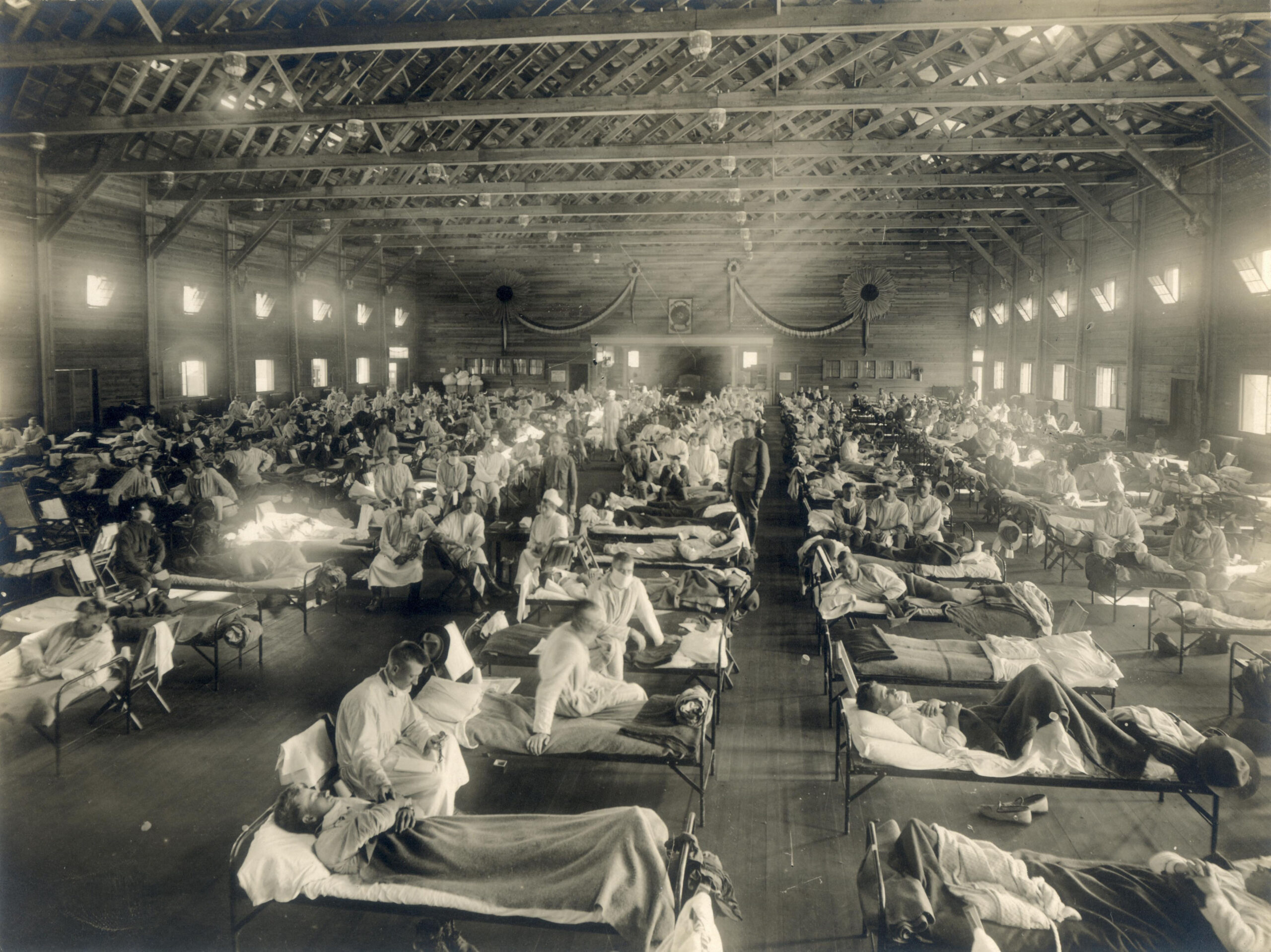

There is no certainty where the particularly lethal H1N1 strain of flu did originate from. Spinney identifies an army base camp in Kansas – a jump-off point for soldiers being sent to the front in Europe – as the most likely origin.

She also reports on the work of scientists who have successfully recreated the H1N1 virus and studied it, finding significant differences between the first wave of the virus and the second.

The second – and by far the most deadly – wave is known to have started on the Western Front, and viruses are thought to mutate more rapidly when inhabiting malnourished bodies. This, combined with the use of poison gas – some of which encourage mutation – were, Spinney surmises, likely causes of the lethal properties of the pandemic’s second wave.

And, of course, the global troop movements resulting from the war were the main transmission belt for the pandemic. In other words, while the existence of viruses might be natural, the development of the 1918 pandemic, like today’s, was driven by a capitalist system in crisis.

Viruses also lay bare the inequality created by the capitalist system, and its inability to care for the health and well-being of the population. Medicine was obviously far less advanced in 1918 than today. Scientists had not yet realised that the flu was a virus, never mind developed a vaccine. Nonetheless, it was understood that the flu was highly contagious and was spread via human proximity.

Like with Covid-19 today, it was understood that handwashing and social distancing were vital to stopping the spread of the disease. Social isolation to stop the spread of disease had already been well established over centuries. Nonetheless, in many countries, including Britain, no serious measures were taken.

In Britain, despite a propaganda campaign telling people to avoid crowds, no concrete measures were taken to shut workplaces or prevent overcrowding on public transport. 250,000 people died, but the cabinet never discussed the pandemic, and it was only discussed in parliament at the end of October 1918, weeks after the second – and most deadly- wave of the virus had hit the country.

This approach remains the default for British capitalism today, and was the Tories’ initial plan for dealing with Covid-19, relying on the development of ‘herd immunity’. As 1918 shows, that potentially meant accepting hundreds of thousands of deaths.

‘Asian flu’

The same approach was taken by the Macmillan Tory government in 1957, with the arrival of ‘Asian flu’. Tory Health Minister John Vaughan-Morgan predicted that 20% of the population would catch it, but also described it as no more than “a heaven-sent topic for the press during the ‘silly season’.”

Public events went ahead as normal, including the Tory party conference, at which Macmillan didn’t even mention the flu in his speech! That flu pandemic is estimated to have infected nine million Britons and killed 30,000.

This time, the strategy of waiting for herd immunity was looking like it might kill numbers closer to 1918 than 1957. Belatedly, it became clear to the Johnson government that its strategy of inaction would threaten a serious public revolt as the number of deaths spiralled. It therefore beat a hasty retreat to lockdown.

Now, however, the Tory cabinet is trying to lift it without having implemented the necessary testing and tracing, nor having secured other robust health and safety measures.

The effects of the 1918 pandemic were not just the immediate loss of life. Babies born in 1919 were an average of 1.3 millimetres shorter than those born in the surrounding years as a result of so many having been exposed to the virus in womb.

Spinney argues that Spanish flu “fanned the flames that had been smouldering since before the Russian revolutions of 1917” by “highlighting inequality” and “illuminating the injustice of colonialism and sometimes of capitalism too”.

She points, for example, to the horrific 18 million people who are estimated to have died in India from the flu, combined with the effects of a drought. Despite mass starvation, British imperialism did not halt the export of wheat until the crisis had already been at its peak for weeks.

She describes how “rivers became clogged with corpses because there wasn’t enough wood to cremate them”.

The relief effort was mainly led by organisations linked to the Indian independence movement, and Spinney argues, played an important role in fuelling that movement.

This is one of countless examples of the callous cruelty of British imperialism. Another was the malaria epidemic in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in 1935.

The report to the Royal Medical Society by the British officer responsible for dealing with the epidemic simply dismisses the measures which would have been necessary to destroy the mosquitos’ breeding grounds as “quite out of proportion to the benefit expected,” ie stopping around a quarter of the total population suffering from malaria, with around 50,000 dying!

The anger created by imperialism’s disregard for human life, combined with the role of socialist activists organising to fight the epidemic, were key to the founding of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party at the end of 1935, which became a mass Trotskyist party.

Revolutionary wave

In 1918, the direct effects of the pandemic can’t be separated from the revolutionary wave that swept large parts of the world in the wake of World War One and the Russian revolution.

Spinney argues that the flu was central to the 1918 general strike which engulfed “well-ordered” Switzerland, for example. No doubt it was one factor, but so were the fall in wages by a quarter and the revolution developing in neighbouring Germany.

Spinney also points to the role of the flu pandemic in convincing capitalism “that it was no longer reasonable to blame an individual for catching an infectious disease”. She argues this led to “many governments embracing the concepts of socialised medicine – healthcare for all, free at the point of delivery.”

There is no doubt it strengthened the fight to demand free healthcare by the workers’ movement in many countries. However, as she also explains, it was Russia in 1920 that “was the first to implement a centralised fully public healthcare system”.

Spinney adds that it wasn’t universal because it didn’t cover rural populations, “but it was a huge achievement nevertheless, and the driving force behind it was Vladimir Lenin”.

She points out that doctors feared persecution after the revolution but “Lenin surprised them by soliciting their involvement at every level of the new health administration, and in the early days, this placed particular emphasis on the prevention of epidemics and famine.”

In 1924, the Soviet government called for medical schools to produce doctors who had “the ability to study the occupational and social conditions which give rise to illness and not only to cure the illness but to suggest ways to prevent it.”

In Russia, in 1917, the working class succeeded in overthrowing capitalism and beginning to build a new society for the first time in history. Economically ruined and politically isolated after defeating imperialist wars of intervention, and after the defeat and failure of revolutions elsewhere, in particular in Germany in 1923, the revolution later degenerated under an emerging caste of state and party officials headed by Stalin. But what Spinney is describing is the attempt to create a democratic workers’ state, based on a planned economy, and the huge steps forward that led to for healthcare.

In passing, she also refers to the Soviet Union developing a flu vaccine before any other country on earth, and giving it free to all factory workers. In reality, it was the existence of the Soviet Union, and the fear of the capitalist classes of the world that workers in their own countries might follow Russia’s lead, that had the biggest effect in driving forward the development of public healthcare in other countries.

Prospects

In Britain, it took until 1948 for the National Health Service (NHS) to be established. Successive pro-capitalist governments – Tory but also New Labour – have privatised and cut huge swathes from it.

The current pandemic has forcefully driven home why we have to fight for the rebuilding of the NHS, dramatic pay increases for its workforce, and the throwing out of the privateers who are making fat profits from it.

Movements in defence of the NHS will be an important feature of the coming months and years. So too will movements against the gross inequality created by capitalism which – just as in 1918 – is being laid bare by the pandemic and will, as Spinney puts it about the events of a century ago, “fan the flames of revolt.”

- Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World is published by Cape.