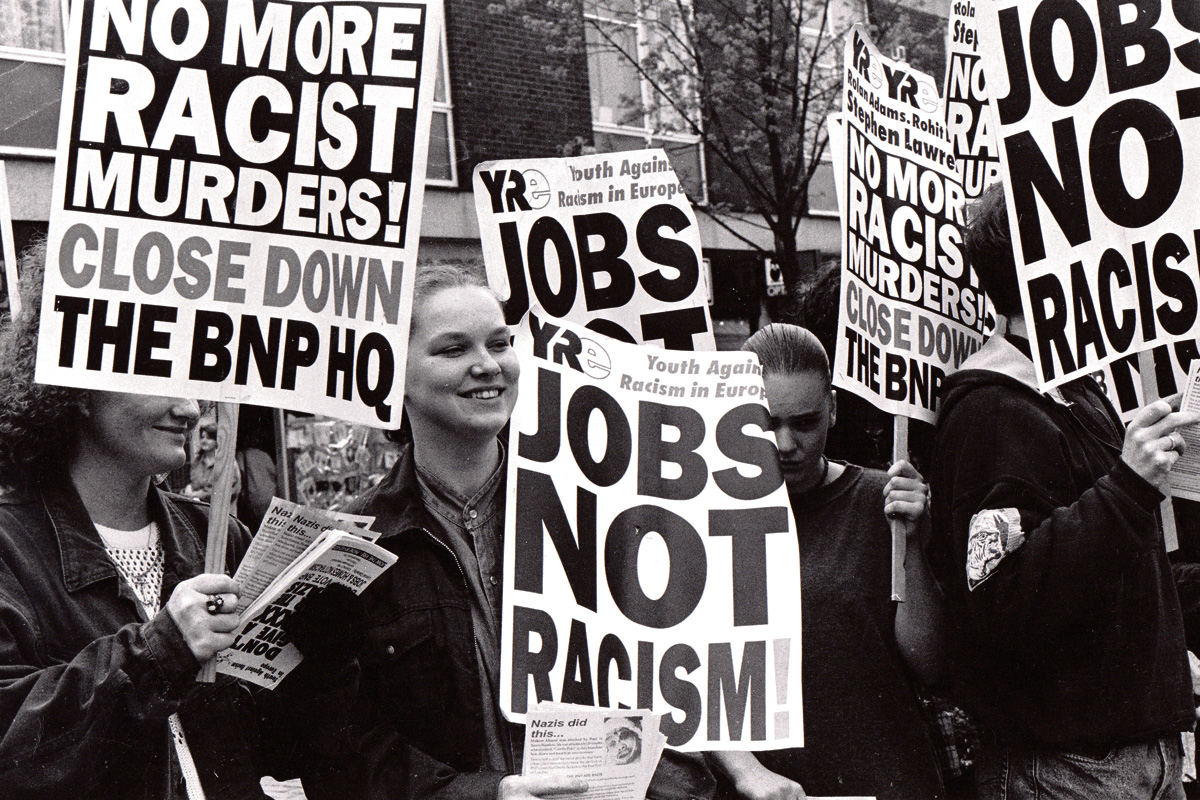

On 16 October 1993, over 50,000 people took part in a mass protest demanding that the headquarters of the far-right British National Party (BNP), then based in Welling, be shut down. Youth against Racism in Europe (YRE), which was led by supporters of Militant – the Socialist Party’s predecessor – played a central role in these events. To mark the anniversary, here we carry edited extracts from chapter 51 of ‘The Rise of Millitant‘ by Peter Taaffe, outlining the history of the struggle against the BNP in this year. It is a history which is rich in lessons for fighting the far right today.

The murder of Stephen Lawrence in April 1993 in south-east London was the fourth such racist murder in the area in three years. This was the area where the fascist BNP had its headquarters.

Stephen’s murder in Eltham – he was stabbed twice: once through the shoulder and then through the heart – was completely unprovoked.

In 1992, 16-year-old Rohit Duggal was stabbed to death by a gang of white youths in the same road where Stephen Lawrence was killed. Between August 1990, and May 1991, 863 incidents of racist attacks and harassment were reported to the Greenwich Action Committee against Racist Attacks. YRE demanded the closure of the BNP’s ‘bookshop’ – effectively its headquarters.

This demand was aimed in particular at the Tory Bexley council which had refused to accede to the pressure that had been exerted against it prior to Stephen Lawrence’s murder. YRE initiated the call for a mass demonstration on 8 May.

The 8 May demonstration was the largest anti-racist mobilisation for a decade – more than 8,000 marched. Significantly, it mobilised a wide layer of black youth who marched together with white workers and youth. The police assaulted the demonstrators, attempting to create the impression of a riotous, uncontrolled ‘mob’.

The demonstration was, however, very well disciplined and effectively stewarded by the YRE. It was this which prevented serious injuries, possibly including death, being inflicted by the police.

The Anti-Racist Alliance (ARA) refused to participate in a joint demonstration in Welling, preferring to march on the same day, totally ineffectively, through central London. The Anti-Nazi League, controlled by the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP), also refused to join in a united non-sectarian demonstration.

They held a demonstration one week after the massive and successful 8 May demonstration. It attracted no more than 2,000 people.

An unprecedented degree of pressure had been exerted on councillors, but Bexley’s Tory council remained unmoved. To discuss the next steps, all the anti-racist organisations – the YRE, ARA, the ANL, together with organisations like the Indian Workers’ Association (IWA) – had been brought together under the banner of the Stephen Lawrence family to discuss the next stage of the campaign.

At the first meeting of this committee, the YRE representatives proposed a national unity demo to pass the BNP headquarters on 16 October. In response to this ARA representatives proposed a march through central London instead, which was later supported by the ANL representative.

The YRE had no intention of organising a demo in competition to one organised by the ARA and Stephen Lawrence’s family. In the interests of unity, the YRE proposed organising a Bexley demo at a later date to avoid conflict with ARA’s central London initiative. This was despite the fact that the YRE believed that a demonstration through central London would be seen as missing the target. However, at the campaign’s next meeting, the ANL did a complete somersault.

Without any discussion or consultation, their representatives announced they would be marching to the BNP HQ on 16 October. Leaflets and posters had been produced and transport already booked. The YRE argued for unity. They asked ARA to reconsider, and met with the ANL and tried to persuade them to change the date of their demo. Both groups refused to change their minds. We declared:

“Faced with the flat refusal to reorganise their demo on a later date and given that the key task is to close down the BNP, Militant Labour believes anti-racists and anti-fascists should mobilise for a mass turnout on the Bexley demo.”

In September, the BNP secured a by-election victory in the Millwall ward in Tower Hamlets. This acted like a crack of thunder to waken youth and workers into action.

The victory of the BNP resulted from years of neglect by right-wing Labour in the area.

Racism had then been fuelled by the scandalous actions of the Liberal-dominated Tower Hamlets council, which had blatantly issued racist leaflets as a means of holding on to control in the area.

Council workers immediately walked out when the BNP victory was announced. Two hundred out of a total staff of 600 attended an emergency meeting convened by stewards the day after the election result.

Brick Lane

Phil Maxwell, a Tower Hamlets Labour councillor, called for a complete boycott of Derek Beackon, the new BNP councillor. The election results also galvanised the YRE into organising the youth against BNP paper sellers in Brick Lane. On Sunday 19 September, 100 YRE members occupied the space in Bethnal Green Road where the BNP usually sold. At about 9am some six or seven fascists turned up and started baiting the anti-fascists. They waved a Union Jack and shouted fascist chants.

The police protected the Nazis, letting them take photos of anti-Nazis. The fascists attempted to provoke a confrontation. After about an hour 200-300 anti-fascists from the YRE, the ANL and other local people assembled. Then the so-called ‘toughs’ of fascist group Combat 18 ran for their lives as the anti-fascists and anti-racists tore through the police lines to get at them.

The victory in Brick Lane gave a further spur to the campaign against the BNP. Over 1,000 demonstrators turned up on 26 September and the BNP never arrived in Brick Lane for their usual paper sale.

It was subsequently revealed that 50 Nazis were arrested on the way to the sale. The fact that the police intervened in this way was itself a reflection of the highly successful campaign launched by the anti-racists and anti-fascists.

Further demos

On 3 October, a 3,000 strong anti-racist anti-fascist demonstration, with a large and very vocal contingent from the local Asian community, marched through London’s East End. The demonstration had been initiated by Youth Connection, representing Asian young people.

All of this culminated, on 16 October, in the magnificent anti-racist demonstration of 50,000 which streamed through the streets of Welling in a determined attempt to shut down the Nazi headquarters. This action ranks alongside some of the great anti-fascist, anti-racist demonstrations of the past such as Cable Street, the march through Deptford in the 1970s and the earlier 8 May demonstration.

The demonstration was called under the banner of ‘unity’, symbolising unified action by the main anti-racist, anti-fascist organisations. But as the 50,000 demonstrators were assembling, the outline of future trouble was symbolised by the horses and riot police who lined the hills.

There had been intense discussion about the route between the organisers of the demonstration and the police in the days leading up to the demo. The YRE members in the meetings of stewards and the organising committee beforehand had warned that the police were likely to wade in. Therefore, measures had to be taken to safeguard the demonstration.

The YRE argued for proper stewarding, with organised and identifiable stewards and for a system of communications so that stewards could be in radio contact. The ANL and SWP leaders ridiculed this idea as a “Dad’s Army” tactic. Incredibly, they even argued that the stewards’ bibs and walkie-talkies looked militaristic and “intimidating”.

Police

In opposition to police armed to the teeth, with riot shields and on horses, they argued for a sit-down protest! But for the enormous courage of the stewards, led by the YRE and joined by ordinary demonstrators and some courageous rank-and-file members of the SWP and ANL, disaster could have followed the predictable police attack.

The police’s tactics in the run-up to the demonstration were quite simple: ‘Predict trouble in advance and we’ll get away with anything on the day.’

As the march continued to the junction of Upper Wickham Lane and Lodge Hill, the marchers were confronted with an amazing situation. Every road was blocked by police, riot police with shields and batons.

No attempt was made to direct the march up Lodge Hill (the police’s preferred route). Instead, horses and police lined up facing the demo across the entrance to Lodge Hill. The road to the BNP bunker was full of riot police but unlike every other road there were no barriers.

It was clear that this was because the riot police on horseback would be able to charge the demonstrators without having to move steel barriers. As the demonstration halted, riot police charged into the crowd. One steward from Glasgow commented:

“I came face to face with the police and many of them had ripped off the identification numbers on their arms. I soon saw why. The police charged the demonstration and many people were crushed up against the railings. People were running in panic away from the blows of the police.

“They just waded in. We were pulling people out and passing them on to safety. Some of them were really close to asphyxiation – our stewards saved lives. While all this was going on, the police were still charging, batoning people, climbing over bodies to get to the people behind us.”

It was clear the police were following the script written by their Tory masters whose aim was to simply portray the march as “violent left-wing fascists”.

Eventually, YRE chief stewards managed to negotiate with the chief of the riot police to withdraw his troops 30-40 yards away to stop any more conflict.

All the stewards then linked arms to ensure the demo was defended. Many ANL members worked hand in hand with YRE stewards. Julie Waterson, the demo’s chief steward, was on the front line with YRE stewards until she got batoned by the police. But there were no ANL leaders to be seen after this.

Only the heroism of the stewards, with the YRE giving the main lead, women as well as men, made it possible through tight organisational discipline to stop the police from going on a full-scale rampage. At the end of the demonstration, when the marchers were dispersed, the police, particularly the riot police, attacked in a cowardly fashion from behind.

Lessons

Many lessons were learnt on that day. It was clear that Militant and YRE members were the only ones who had any serious idea of how to steward such demos.

Nevertheless in the wake of the demonstration Militant called for a “united front of all anti-racist organisations with the trade union and labour movement involved.” At the same time we argued that anti-fascist activity needed to be linked with a programme on jobs, homes, education, and so on.

The 16 October demonstration represented a turning point. It brought out into the public domain the real character of the BNP and prepared the ground for the discrediting and subsequent defeat of Beackon in 1994 and the successful closure of the BNP’s HQ in July 1995.

However, none of this would have been possible without the determined action and leadership provided by organisations like the YRE which, avoiding the sectarian pitfalls of the ANL and SWP, sought to build the widest possible movement of youth and workers against the racist and fascist threat.