Britain 1911-1914: The great unrest – lessons for today

100 years ago the working class responded to the terrible conditions imposed on them by taking mass industrial action in what became known as the ‘great unrest’.

The Liberal Party in government… Militant workers disillusioned with the Labour Party… A decade of growing divide between rich and poor… And the biggest strike wave for more than 20 years, shattering the arrogance of the government and employers, and shaking the complacency of the majority of trade union leaders.

Jim Horton

This could read as a perspective for 2011, particularly given the pressing need for workers to take decisive industrial action against the current government’s savage cuts package. In fact it describes the situation 100 years ago, when throughout 1911 mass strikes of miners, seamen, dockers, carters, tramwaymen and railway workers ushered in a period of industrial unrest on a scale not previously experienced, and which was only cut across by the onset of World War One.

Of course there are many differences. The Liberals were in government, having been re-elected in 1910 following their victory in 1906 on a pledge of opposition to ‘landlords, brewers, peers and monopolists’.

After many years in power the Conservatives were the main opposition party. The recently formed Labour Party was still a minor party electorally.

In contrast to today the economy was experiencing growth, although Britain was struggling to manage the economic challenge from America and Germany. There were signs that economic growth was coming to an end before the outbreak of war in 1914.

In stark contrast to Clegg’s embrace of Tory policies, the Liberal government had initially enacted new progressive, although limited, welfare measures and legislation giving unions immunity from being sued when taking industrial action.

Yet it will be the striking parallels with today that will be of most interest to workers looking for a way to resist the Con-Dem assault on public services and jobs.

The period from 1901, which has been described by many historians as the Edwardian summer, was in fact a bonanza for the rich. Like the first decade of this century, the divide between rich and poor widened.

By 1910, citing financial constraints, Liberal reforms were coming to an end. Even prior to 1910 grievances had accumulated over poor working conditions, discipline at work, and the failure of wages to keep pace with rising prices. After increasing for many years, real wages had ceased to grow from the turn of the century, and had declined by 10% by 1910. In the following years retail prices rose while wage rates stagnated or fell as the rich wallowed in their new-found luxuries.

Like today, the close ties between many union leaders and the right wing of the Labour Party, and the refusal of both to mount a challenge to capitalism, meant they were reluctant to sanction industrial action. This forced workers to take unofficial action, which was then denounced as irresponsible by Labour’s hierarchy.

100 years ago the working class responded to the terrible conditions imposed on them by taking mass industrial action in what became known as the ‘great unrest’. The Liberal government was already beset with a political and social crisis, including looming civil war in Ireland and mutiny at the top of the armed forces over Home Rule.

The civil unrest of the women’s suffrage movement added to the government’s woes. But it was the inspiring strike action of the organised working class, in many cases in defiance of their national leaders, that had the potential to transform political and social relations in Britain.

It was the breadth and spontaneity of the action throughout 1911 and 1912 that shook the political establishment to the core, and took the trade union leaders unawares. Combining concession with coercion, the government was forced to intervene directly in negotiations while deploying troops against striking workers. The union leaders struggled to regain authority and control over unofficial action as workers rejected their attempts to reach shoddy agreements with the employers.

School students

There were 872 different strikes in 1911. There were 18 separate disputes in Lancashire alone. Even school students were affected by the militancy of the times. On 5 September school students in Llanelli, Wales, protested against the caning of a boy. Within days pupils in more than 60 towns across Britain took to the streets to express their grievances. One boy told a Daily Mirror reporter: “our fathers strike – why shouldn’t we?”

The longest running strike action in 1911 took place in South Wales. It was triggered in September 1910 by 70 miners in a dispute over tonnage rates to be paid on a new difficult seam at the Ely pit owned by the Cambrian Combine.

From November, after rejecting a compromise deal agreed by their union leaders, 12,000 miners working for the Combine were engaged in a protracted battle. It eventually ended in defeat in October 1911 after the Miners Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) refused to call a national strike.

It was a bitter dispute with pitched battles between strikers and troops and imported police from London, who were assisting scab [strike-breaker] labour. In Tonypandy in November 1910 one striker was killed and some 500 injured.

The strike was run by an unofficial joint lodge committee, reflecting opposition to the conciliatory policy of the union leadership throughout the coalfield. Militants leading the committee were elected to all the vacant places on the union’s South Wales executive in January 1911.

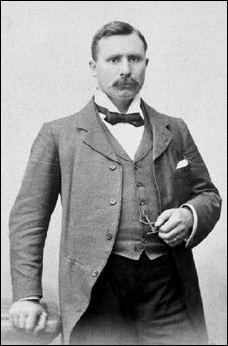

Tom Mann (1856–1941) was elected President of the newly-formed Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union. Ben Tillett was General Secretary

In 1910 the Transport Workers Federation (TWF) had been formed, bringing together the unions of seamen, dockers and carters under the leadership of syndicalists Tom Mann and Ben Tillet. A vigorous recruiting campaign was launched. In a dispute over wages seamen went on strike from 14 June 1911, starting in Southampton and quickly spreading to other ports.

They were soon joined by dockers and carters, taking their own union leaders unawares. Strike action even affected unorganised ports, such as Hull. A 15,000 strong meeting of Hull dockers rejected a proposed settlement with cries of: “Let’s fire the docks”.

In Liverpool the strike movement spread to the railways in a dispute over pay. The district committee of the TWF declared a general transport strike throughout Liverpool, which resulted in magnificent solidarity action across the city.

The government’s Board of Trade conciliator toured the affected areas, simultaneously negotiating with 18 different unions in an attempt to broker a solution. One historian commented that the longer settlements were delayed the more the strikes took on the character of a social war.

Troops were already being deployed to assist the employers and their scabs. Salford was subject to a virtual military occupation. In Liverpool, with a gunboat standing by on the Mersey, the army shot dead two strikers following three days of guerrilla warfare in the streets of the city centre. With thousands of troops stationed, London was a city under virtual martial law.

However, with 120,000 workers closing almost every provincial port in the country the employers’ strikebreaking organisation was exposed as ineffectual. Eventually the shipping industry bosses went down to defeat, forced to concede wage increases.

The London docks had not initially been part of the national action, as union leaders believed a settlement could be reached without a strike. 80,000 dockers and other transport workers rejected a union-backed deal and took unofficial strike action.

Forced into line, the union leaders declared the strike official, and within two weeks sufficient gains were made to call off the action. Some of the poorest sections of other workers were also drawn into this magnificent movement, including 15,000 women in the sweated workshops of Bermondsey, London and cleaners working for London County Council.

Meanwhile, the Liverpool railway strike had spontaneously widened across the country. The Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants leaders had initially rejected calls for a national strike. But, unable to stem the wave of unofficial strikes, they were compelled to officially endorse the national stoppage as 250,000 railway workers took action over terms and conditions and union recognition.

In Liverpool, mass pickets were mounted and the strike committee issued permits for the movement of essential supplies of milk and bread, and overseas mail. In some areas of the country miners came out in sympathy with the railwaymen. The government placed the army at the disposal of the railway companies. Troops stood by to overawe disorder in more than 30 places, including 600 in Llanelli where soldiers killed two strikers. However, within two days, alarmed at the widespread support for the strikers, the government backed down.

Liberal home secretary Winston Churchill declared in the House of Commons on 22 August that, had the railway strike not ended quickly, industrial England would have been hurled into “an abyss of horror”.

Using the pretext of the ‘Agadir’ crisis (the threat of war over German ambitions in Morocco), chancellor David Lloyd George persuaded the employers to accept conciliation. Eager to regain control over recalcitrant militants, the union leaders readily called off the strike.

The settlement did go some way towards achieving union recognition, but failed to address grievances over long hours, low wages and iron discipline. However, the strike did boost the confidence of railway workers and led to an increase in union membership. Further unofficial strikes on the railways broke out during 1913.

The labour unrest continued beyond 1911. The Times warned that: “The public must be prepared for a conflict between Labour and Capital, or between employers and employed, upon a scale as has never occurred before”.

During 1912, hundreds of thousands of workers engaged in industrial action, including Lancashire cotton weavers, Dundee jute workers, London dockers and carters, and most notably coalminers.

Miners go into battle

Despite losing their dispute, the action of the Cambrian miners had served to force the leaders of the Miners Federation of Great Britain to conduct a national ballot on establishing a minimum level of earnings for all underground workers. In January 1912 miners voted four to one for a national strike.

Unimpressed with the government’s response, nearly a million miners participated in the first ever national miners’ strike from 1 March 1912. The Times declared the strike: “The greatest catastrophe that has threatened the country since the Spanish Armada”. One Tory MP advocated siege rations and martial law to defeat “socialist trade unionism”. In Conservative circles there was talk of revolvers being stockpiled to be used against working class revolt.

Fearing widespread civil unrest, the government abandoned its stance of non-intervention. Within a month the government had rushed a minimum wage bill through Parliament. A week later prime minister Asquith broke down in the Commons under the strain.

The bill provided for arbitration to settle the level of minimum wages, district by district. This was rejected by miners in a second ballot, but citing the smaller majority for continuing the strike action, and fear for the unity of the federation, the executive called off the strike.

Not all the district settlements gave miners the increases they had sought, but the union had been strengthened and it had demonstrated that action could force concessions.

Lenin, one of the leaders of the successful Russian revolution, recognised the broader significance of the coal dispute when he wrote in 1913: “Since the miners’ strike the British proletariat is no longer the same. The workers have learned to fight… In Britain a change has taken place in the balance of social forces”.

In 1913 the number of strikes peaked at 1,459. In January, London cab drivers struck against a cut in their earnings. By 20 March the employers’ federation had capitulated. In the autumn the taxi drivers’ union also led London’s busmen in a successful strike for union recognition.

The mass strike action of seaman, dockers and railway workers of 1911-12 led to a general upsurge of unorganised or badly organised workers in a wide range of other industries. This boosted the membership of the general unions, particularly the recently founded Workers’ Union, which saw its membership grow from 23,000 at the end of 1912 to 91,000 by December 1913.

This phenomenal growth was greatly assisted by the Workers’ Union’s role in the industrial action that spread across mainly unorganised metal industry workplaces in the Midlands. From November 1912 through to July 1913, 50,000 workers, including large numbers of women workers were involved. Faced with such action, and widespread public sympathy, the employers were reluctantly forced to meet with the Workers’ Union and to grant a minimum wage.

In Dublin in 1913 the transport workers were engaged in a bitter eight-month strike against a determined attempt by the employers to destroy their union with armed force. The dispute ended in a draw, following the failure of Britain’s trade union leaders to organise solidarity action.

In early 1914 the London master builders locked out their workers in response to a rash of unofficial strikes during 1912-13 over opposition to the deployment of non-trade unionists. After three months the employers withdrew their document requiring workers to work with non-union labour. The strikers refused to return to work until further concessions were granted. They held out until the outbreak of war in August.

Stewards’ movement

While the number of strikes ebbed during the war, tension between the classes, and union members’ dissatisfaction with their leaders did not disappear. Major strikes in the engineering sector resulted in industrial militants creating the first national shop stewards’ movement.

From 1910 until the onset of war the best union activists had correctly concluded that the lack of a lead from the tops of the unions would not prevent them from organising necessary industrial action from below. However, it was not until during World War One that union stewards set up local workers’ committees in towns and cities across Britain. These workers’ committees were born out of industrial struggle and led to the establishment of the first national shop stewards’ movement in Britain.

The militants who led the industrial action from 1911 were generally socialists, but also greatly influenced by the ideas of syndicalism and industrial unionism. The shop stewards’ movement adopted a position of supporting the union officials as long as they represented their members, but acting independently where members’ interests were misrepresented. Their weakness was not having a strategy to transform the unions.

The strike leaders also had political shortcomings. They correctly criticised the reformist leadership of the Labour Party, but they mistakenly stood apart from the Labour Party at a time when it was establishing itself as the mass party of the working class. The politics of syndicalism could never provide a realistic alternative to capitalism or offer a viable means of changing the system. However, industrial militants did learn from the rich experience of the shop stewards’ movement, and its leaders played a key role in the formation of the Communist Party in 1921.

Lessons for today

Today, as we face the most savage cuts in a generation, union members desperately need fighting trade unions to protect jobs and services. The National Shop Stewards Network (NSSN) can play a key role in galvanising workers’ opposition to all cuts in jobs and services. It will be from mass industrial action that the potential of the NSSN can be realised.

In contrast to 1911, vicious anti-union laws now prohibit unofficial action, but where the union tops refuse to organise strikes in defence of jobs and services, workers will have no choice but to defy the law and take unofficial action.

Politically, with New Labour an avowed party of big business, committed to drastic public sector cuts and opposed to unions taking strike action, workers will need to establish a new mass party which supports workers’ struggles and fights for a socialist solution to the misery of capitalism.

Working days lost through strike action

1911-1914 average – 18 million (70 million in total)

1912 – 40 million+

1921 – 85 million

1926 – 162 million

1979 – 30 million

1984 – 27 million

Lloyd George looks at the workers’ movement – with trepidation

In his memoirs, David Lloyd George accurately outlined the situation confronting his class on the eve of World War One: “In the summer of 1914 there was every sign that the autumn would witness a series of industrial disturbances without precedent.

“Trouble was threatening in the railways, mining, engineering, and building industries, disagreements were active not only between employers and employed, but in the internal organisation of the workers.

“A strong ‘rank and file’ movement, keenly critical of the policies and methods of the official leaders of trade unionism had sprung up and was gaining steadily in strength.

“Such was the state of the home front when the nation was plunged into war.”