Nick Fray, Newcastle Socialist Party

One hundred years ago the ‘beautiful game’ came to be dominated by women.

World War One saw a generation of male footballers conscripted and sent to fight and die on the Western front and around the world. Women suddenly found themselves in great demand at munitions factories around the country. Over 900,000 women worked in them.

Munitionettes worked with very hazardous chemicals on a daily basis without adequate protection. Many worked with TNT.

Prolonged exposure to nitric acid turned their skin a yellow colour. These women were popularly called canary girls.

The chemicals also created serious health risks for the munitionettes, including severe harm to the immune system, liver failure, fertility problems, and many other very serious side effects.

Another hazard was the risk of explosion. One explosion at a munitions factory in Chilwell near Nottingham in 1918 killed over 134 workers and injured hundreds more.

Most factories employed a welfare officer to monitor the health and behaviour of their new female workforce, and actively encouraged them into recreation in what little spare time they had. Between long, heavy and very dangerous shifts, the women workers began playing various sports.

Football became the game to play. The informal kickabouts at their breaks became popular for the women. An activity that was previously considered unsuitable for the ‘delicate female frame’ was now encouraged as good for health, well-being and morale.

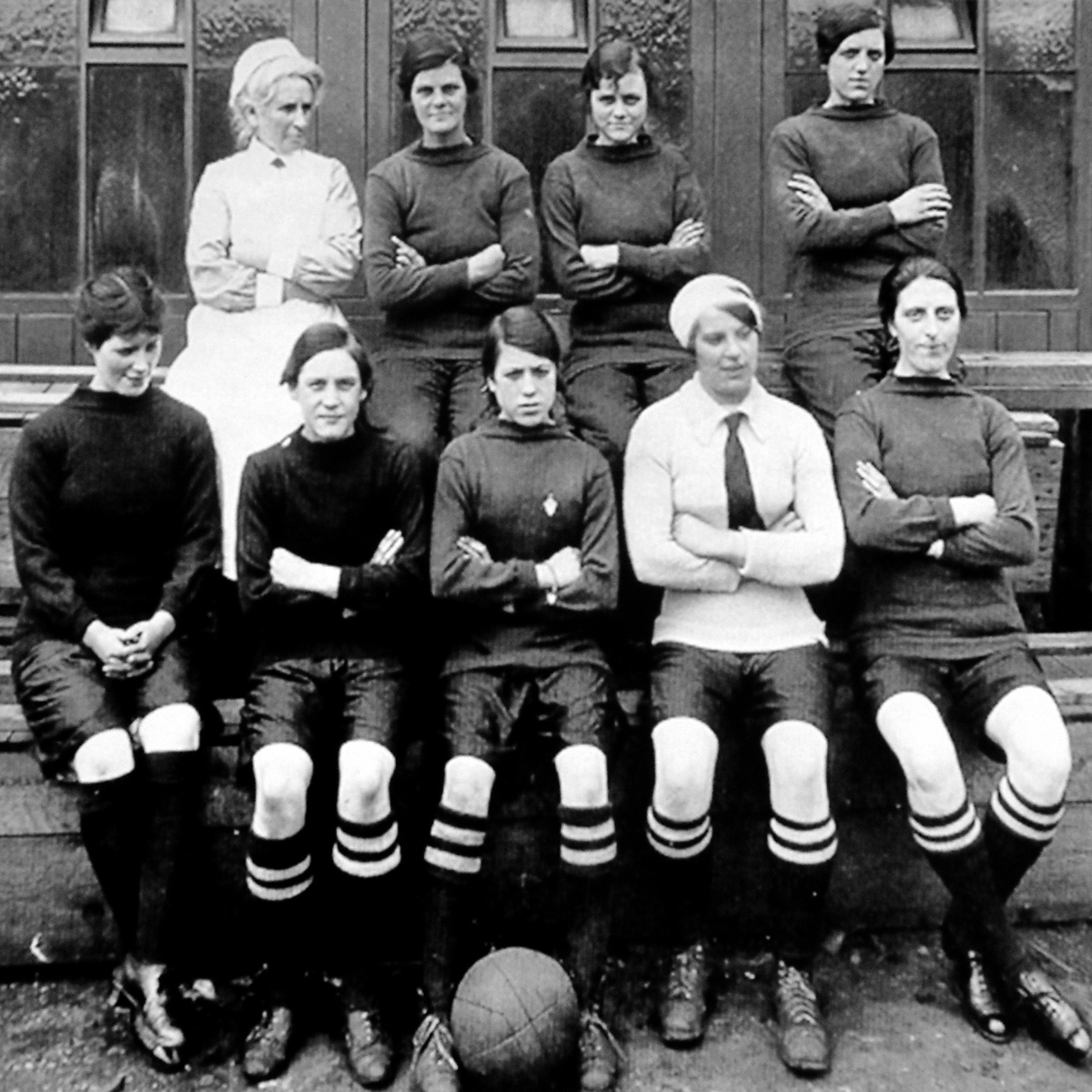

As the war progressed, the women’s game became more formalised, with football teams emerging from the munitions factories. The teams which sprang up – usually named after the factories they worked in – filled a vacuum. They represented, for a brief moment on a Saturday afternoon, an important means of escape for both players and spectators from the war’s horrors and factory monotony.

Killed off

Women’s football was already established, but until the war it hadn’t been well received. Initially women footballers played in skirts, were regarded as a novelty and were frequently ridiculed, but their skills, talent and enthusiasm soon saw them being taken seriously, with large crowds watching them play.

Bella Reay played for Blyth Spartans, the biggest and most successful of the women’s teams in the north east of England. Bella Reay scored a colossal 133 goals in one season.

Once the war ended the munitions factories closed and women were forced back into domestic servitude. On 5 December 1921 the Football Association governing body voiced strong opinions about football’s unsuitability for women, and effectively killed off the rise of women’s football, banning clubs from allowing women’s games to be played at their grounds.

Blyth Spartans Ladies folded in 1919, but Bella, among others, was to go on and play for other teams on unofficial grounds. Some women’s football matches were organised in 1921 to raise funds for miners and their families during a three-month coal strike.

It was a period when miners and other workers struggled to stop savage wage cuts imposed by the Tory-Liberal government and mine-owning industrialists (see ‘Black Friday’).

Golden era

The best women’s football team around this time was arguably Dick Kerr Ladies in Preston.

Their renowned striker Lily Parr is recognised as the greatest goal scorer in English history, male or female, since she reputedly scored more than a thousand goals during her 31-year career between 1920 and 1951.

One Dick Kerr game attracted 53,000 spectators at Goodison Park, with another 14,000 trying to get in! A bigger crowd than most teams in the top-tier Premier League can attract today. It’s possible, if the ban in 1921 hadn’t been imposed, that women’s football would already be equal in popularity to the men’s game.

With the war now over, devastated communities attempted to put themselves back together. Factories closed and women who had been galvanised and liberated during wartime found themselves being quietly shunted back into domestic life.

A golden era of women’s football was to be short lived. Despite this, a small number of female teams continued for a while, Dick Kerr Ladies being one. But the women’s game became increasingly overshadowed by the return and growth of the men’s game.

It wasn’t until a full 50 years later that women were accepted back onto grounds to play. The game has continued to grow from there. The legacy of the forgotten women’s footballers deserves to be recognised.

These pioneering women not only managed to achieve phenomenal success, they were inspirational, and football owes them for their considerable legacy. Who knows what other achievements and records may have been broken had it not been for the repressive actions of the footballing authorities.