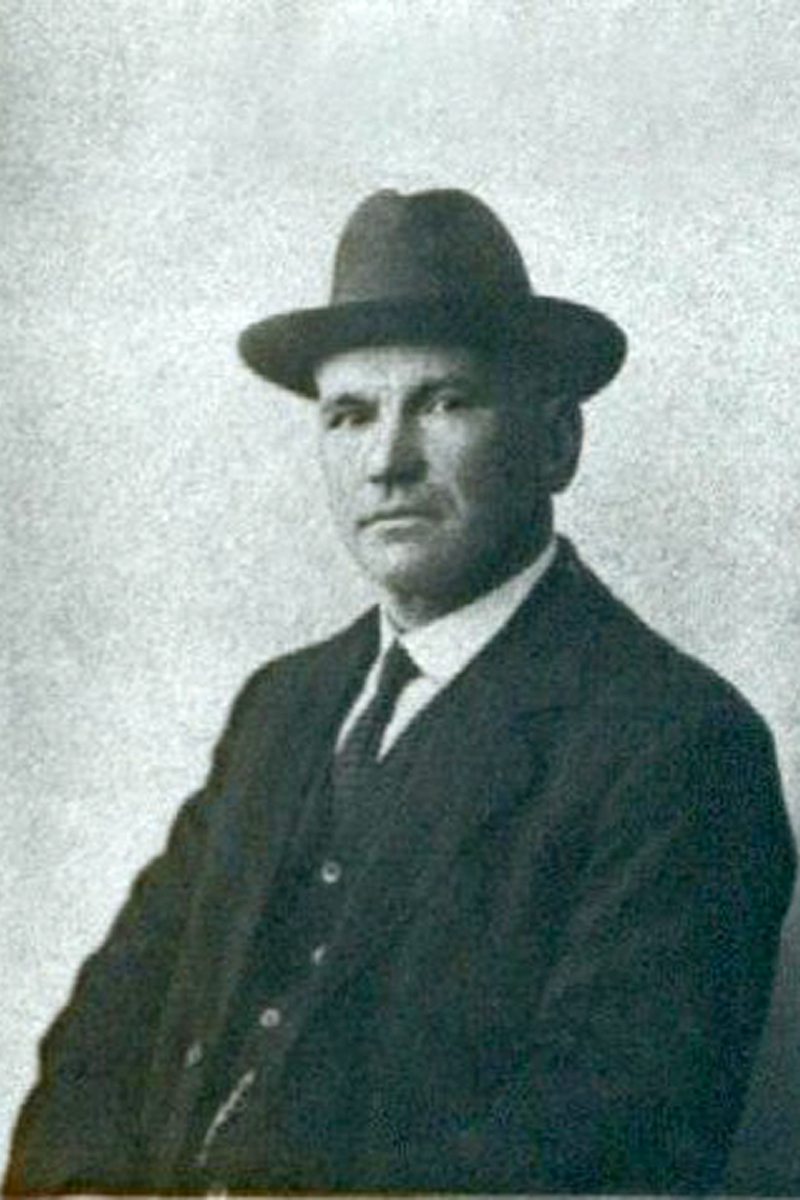

On the recent 95th anniversary of the death of Scottish Marxist John Maclean, Philip Stott, Socialist Party Scotland, looks at Maclean’s contribution to the socialist and working-class movement.

A leader of ‘Red Clydeside’, John MacLean was an outstanding orator, a peerless educator in Marxist ideas.

He emerged as a leader of the anti-war struggle during World War One and as an implacable fighter against capitalism and in defence of the rights of the working class.

His name and contribution is rightly mentioned among the other great Marxists of his generation; Lenin, Trotsky, James Connolly, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

It was a period when the ideas of socialism and Marxism were taken up as a weapon by millions in the struggle against capitalism and blood-soaked imperialism.

Above all, it was a time when the collective experience of the working class internationally drove them towards the conclusion of the socialist revolution.

Mass poverty

John Maclean’s parents had been victims of the brutal Highland clearances and forced to migrate to Glasgow, a city that was an ‘urban inferno’ of explosive industrial capitalism.

One million people – 20% of the Scottish population – lived in or within eight miles of the city. Yet the conditions facing those workers and their families were utterly horrendous. Cholera, typhoid, smallpox and tuberculosis were rife.

It was upon this fertile ground that the ideas of independent working-class politics, socialism and Marxism began to take root.

The Independent Labour Party had been formed in 1892, the Scottish Labour Party was launched in 1888 by Keir Hardie and the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) Conference in 1900 led to the creation of the Labour Party.

The Marxist Social Democratic Federation (SDF) had significant roots in Glasgow, a regular newspaper and effective public spokespeople in the 1880s and 1890s The SDF later became the British Socialist Party (BSP), within which MacLean was also active.

Teacher

John Maclean was already a Marxist when he began work as a teacher in 1900. He organised regular education classes to explain the ideas of economics and capitalist exploitation.

The main textbook was Marx’s ‘Capital’. Shop stewards from the engineering factories and shipyards from across Glasgow were schooled by Maclean.

In 1915, at the height of the rent strikes, the fight against conscription and other mass movements, hundreds attended Maclean’s weekly Glasgow class, including all the leading shop stewards from the major workplaces.

But he was not merely an educator. Maclean wrote and campaigned for municipal public housing, for public control of food and hygiene safety and common ownership of land and agriculture.

The sectarianism and opportunism of the leaders of the SDF led to clashes. The SDF had walked out of the LRC in 1900 because it would not accept socialism as its aim.

Maclean, who joined the SDF in 1903, wrote that he had regarded this as a mistake, while remorselessly criticising the pro-capitalist policies of Labour leaders and a majority of its MPs.

He fought for the idea that Marxists should not be apart from where the working class was but should instead fight alongside these workers looking towards the Labour Party and the Independent Labour Party.

An even bigger clash was to emerge with the leaders of the British Socialist Party on the outbreak of the war in 1914.

The Second International, including the SDP in Germany and the Labour Party in Britain, supported their ‘own’ capitalist class when war began.

Maclean heroically refused to go along with the leaders of his own party like H M Hyndman, who adopted a chauvinist, apologist approach towards British imperialism.

Maclean, alongside Lenin, Trotsky, Connolly, Luxemburg and Liebknecht, came out against the war with an internationalist appeal to the working class.

He threw himself into anti-war activity. In Glasgow the BSP with 500 members split, although a majority backed Maclean.

Undeterred, they organised regular street meetings, sent speakers to the engineering and munitions workplaces, not an easy task given the jingoism that existed at the start of the war. As the anti-war mood deepened thousands came to hear Maclean and others speak.

By February 1915, rumblings of discontent had broken out on Clydeside. A labour shortage gave the workers confidence that they should act and strike action began.

It was a major problem for bosses and profiteers who wanted to use the war as an opportunity to drive down wages and conditions.

This was unofficial action as the Trade Union Congress (TUC) had agreed a policy of ‘industrial peace’ for the war effort. Moreover, strikes were illegal under the Defence of the Realm Act.

To get round this obstacle a strike committee was elected. After the strike ended, this body became the Clyde Workers’ Committee (CWC), with delegates covering all the shipyards and engineering factories. The CWC would go on to play a leading role in the revolutionary events to follow.

The next four years would bring mass working class struggles on the Clyde, the 1917 Bolshevik revolution and imprisonment for Maclean.

Militancy

Pressure on housing was immense. The landlords and their factors (landlords’ agents) saw an opportunity to squeeze more money from tenants and started to raise rents.

Most immediately impacted were working-class women. Mass anger ignited into a campaign of non-payment of the rent increases.

Women, including Mary Barbour, became leaders of the “we are not paying increased rent” campaign. This was a Glasgow-wide movement with marches across the city.

The biggest was in October 1915 when 25,000 marched. Moreover the involvement of Maclean and other BSP members meant that the campaign was taken to the shipyards and engineering factories.

Under mass pressure the government was forced to set up a Committee of Enquiry, but it proposed rent rises, including areas unaffected by rent rises previously.

Maclean called for a mass non-payment campaign of all of the rent, not just the increased amount.

Faced with being unable to collect the rents and being unable to evict tenants, the government and factors went for wage deductions instead. 18 shipyard workers were summonsed to the court on 18 November 1915 to have their wages arrested for non-payment of rent.

A general strike had been called for across Clydeside on 22 November unless the government agreed to a rent restriction act for the duration of the war. A rent restriction act was introduced immediately!

This massive victory reflected the enormous power of the working class and a growing revolutionary socialist outlook among its most advanced layer.

The ruling class also understood the threat, hence the concessions over rents. But this was combined with brutal repression, particularly against its most prominent leader, John Maclean.

Maclean was jailed in November 1915 for five days, after being found guilty of charges under the Defence of the Realm Act for his anti-war activity.

Conscription was introduced in early 1916 and Maclean and the leaders of the CWC mobilised against it. This, of course, was in opposition to the official policy of the TUC and the trade union leaders.

Maclean was found guilty of sedition and sentenced to three years’ hard labour in Peterhead prison. In response, a huge campaign demanding Maclean’s release was launched.

His imprisonment lasted 14 months, until June 1917. By then the February Russian revolution had already electrified the working class across Europe.

The 1917 May Day demonstration in Glasgow saw 80,000 marching in solidarity with the Russian workers, against war and demanding the freedom of John Maclean.

The All-Russian Congress of Workers’ and Soldiers’ delegates sent “greetings to the brave fighter for the International, comrade Maclean.”

The British capitalist class were alarmed at the growing revolutionary upsurge and Maclean was released at the end of June.

His freedom did not last long. The rising revolutionary tide, boosted further by the Bolshevik revolution of October 1917, drove the ruling class to strike again.

In April 1918, Maclean was again found guilty and sentenced to five years imprisonment. But not before he had delivered possibly one of the most famous speeches ever.

Maclean defended himself and his 75 minute address to the jury was a master class in exposing capitalism and war while making the case for socialism.

“I am not here, then, as the accused; I am here as the accuser of capitalism dripping with blood from head to foot,” he told them.

Despite a draconian sentence he was released within seven months. As his daughter Nan Milton wrote: “Demonstrations were being held all over the country.

“When the red banners with slogans ‘Hands off Russia!’ and ‘Release Maclean’, were unfurled at the huge Albert Hall rally in London, the audience went wild….

On 3 December, after his freedom from prison Maclean was met by thousands of workers celebrating his release.

He was carried via a carriage by workers, red flag flying, down Jamaica Street and towards the Clyde.

Russian revolution

The Bolshevik revolution set alight the Clyde as news filtered through of the victory of Lenin and Trotsky.

Lenin himself, as early as 1916, declared: “In all the countries during the war there has been observed a trend of revolutionary socialism…

“To this trend belongs the Bolsheviks of Russia… who are persecuted for the same crimes for which Maclean and Karl Liebknecht are being persecuted.”

In recognition of his outstanding role in the struggle against the war and his support for the Russian revolution, Maclean was elected as Honorary President of the first All-Russian Congress of Soviets in 1918.

Demands for real improvements after the war, the impact of the Russian revolution and rising industrial unrest combined to pose a real threat to British capitalism. The demands for a shorter working week resulted in a mass strike wave.

A general strike was also called for 24 January. On that day all the main yards and engineering shops in Glasgow came out on strike.

The role of the official union leaders, who reflected the interests of the capitalist class as opposed to the shop stewards committees, was to limit the action.

Apart from Glasgow, Edinburgh and Belfast the strikes in other areas of Britain were not organised.

The then secretary of state for Scotland Robert Munro said: “It is a misnomer to call the situation in Glasgow a strike – this is a Bolshevist uprising.”

The ruling class responded to this threat with savage repression. Thousands of police had been mobilised and when the workers assembled in George Square on 31 January they baton charged.

Huge battles took place with workers trying to defend themselves, indeed again and again the police were driven back.

Unfortunately, there were no attempts to fraternise with the troops. Willie Gallacher, a Red Clydeside, leader admitted that: “there should have been a march to Maryhill barracks to enlist the support of the troops… we could easily have persuaded the soldiers to come out and Glasgow would have been in our hands.”

Instead, an agreement was made for a reduction of the working week from a typical 54 hours to 47 hours and the strike ended.

Given the seismic events that erupted on the Clyde, why were there not attempts to form soviets – workers’ councils – and a preparation for power?

A key factor was the relative isolation of the mass strike wave but, crucially, the lack of a Bolshevik-type party in Scotland and Britain at the time.

A period of preparing the ground and building the forces of a disciplined Marxist party among the working class was necessary. But this was not done.

Revolutionary party

John Maclean represented the ideas around which such a revolutionary party could have been built.

Yet, in reality, there was not a distinct revolutionary Marxist party in Scotland or Britain at the time.

The BSP had many outstanding revolutionaries in its ranks, not least Maclean himself. But it was very far from being a disciplined and coherent revolutionary party.

No matter how outstanding an individual may be, and Maclean was an outstanding Marxist, without a revolutionary party to allow for such discussion and clarification mistakes are inevitable.

He mistakenly refused to join the Communist Party of Great Britain, which largely drew together the BSP, parts of the Socialist Labour Party and others when it was founded in 1920.

The key task was to strive to build a genuine revolutionary party in Britain at that time.

Tragedy

The death of Lenin, the isolation of the Russian revolution, and the coming to power of Stalin impacted decisively on the Communist Inter-national and its national sections.

From being an instrument of world revolution, within a decade or so, the International became its opposite: a tool to defend the Stalinist bureaucracy.

Tragically, John Maclean died in November 1923 at the age of 44. At his funeral thousands of workers turned out to say goodbye to their “Dominie” (teacher).

John Maclean’s contribution rightly places him in the front rank of the greatest Marxists of all time.

Today, as capitalism staggers from one crisis to another, the ideas of revolutionary socialism are more necessary and relevant than ever.

- Full article on socialistworld.net

Left Books

Revolt on the Clyde William Gallacher £11.99

John Maclean: Hero of Red Clydeside Henry Bell £14.99

Not Our War: Writings Against the First World War (including John Maclean and Lenin) £12.95

- Please add 10% postage on orders

- Visit leftbooks.co.uk for many other titles 020 8988 8789

- Left Books, PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD