History of the workers’ movement

The 1979 ‘Winter of Discontent’

On 22 January 1979 public sector workers staged a one-day strike calling for an end to low pay and for a shorter working week.

It was the biggest stoppage in Britain since the 1926 general strike. In London, 80,000 workers from the NHS, schools and local authorities marched to parliament to demand the Callaghan Labour government drop its detested policy of pay restraint.

Roger Bannister of Liverpool Socialist Party – an activist in the strike movement – looks back on the ‘Winter of Discontent’ 40 years ago.

History is full of ironies, one such being that, in 1969, James Callaghan MP led a successful cabinet revolt against the document ‘In Place of Strife’, an attempt by Harold Wilson’s Labour government to put legal shackles on the trade unions and their right to take industrial action.

The proposals, put forward by the then employment minister Barbara Castle, were consequently abandoned. Had they become law, many of the strikes which, a little under ten years later, became known as the ‘Winter of Discontent’, would have been illegal, and by then prime minister James Callaghan would have had stronger powers to deal with the crisis!

Formed at the turn of the 20th century, the Labour Party was brought into being by the trade union movement in order to give concrete political expression to the needs and aspirations of working-class people.

However, almost every Labour government since then has lost the support of workers as a result of abandoning this historic mission.

Instead, Labour in office has sought to manage capitalism on behalf of the capitalist class, rather than replacing profit-driven capitalism with a socialist economic system. So it was with the Callaghan government of 1976-1979.

The term Winter of Discontent comes from Shakespeare’s play Richard III, but it was used in an interview by Callaghan, and was seized upon by the capitalist news media to attack the trade unions, both then and ever since.

Background

The 1970s was a period of economic stagnation – after years of capitalist underinvestment – and of high inflation, the failure of Keynesian pump-priming government policies, exacerbated by massive increases in global oil prices.

However, the Tories and their media outlets, and unfortunately right-wing Labour MPs, consistently laid the blame for inflation on the working class, and any pay rises they were able to obtain.

In the year preceding August 1975 inflation had risen by 26.9%! UK governments tended to see their first priority as ‘dealing with’, ie reducing, inflation.

Callaghan tried to ride two bicycles at once, maintaining the confidence in his government of the financiers by acting ‘responsibly’, while keeping the working class on his side by initially avoiding policies such as cutting public expenditure, which would increase unemployment.

Callaghan therefore approached the leaders of the Trade Union Congress (TUC) in order to secure agreement to “voluntary” pay restraint as a key part of the government’s pro-capitalist economic strategy.

The Labour Party leadership were not the only ones at that time to abandon its role of advancing the interests of the working class, because the TUC leaders agreed to this deal with Callaghan!

This was heralded as a historic Social Contract, (soon to be dubbed “Social Con-Trick” by many workers!), under which pay rises were to be held down to levels determined by the government. This commenced in July 1975, and was initially set to last until August 1977.

The Social Contract was never universally accepted within the TUC, and an attempt to abandon it was raised at the 1976 TUC conference – with a call to restore free collective bargaining – but was at that time defeated.

In 1975, pay rises were to be no more than £6 a week, the following year this was reduced to 4.5% with a £4 a week maximum rise, and in 1977 rises were to be held at 10%, as part of what was described by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Dennis Healey, as a “phased return without a free for all” to free collective bargaining. This too was agreed by the TUC.

The government wanted to enforce this policy by applying economic sanctions to any employers that broke it.

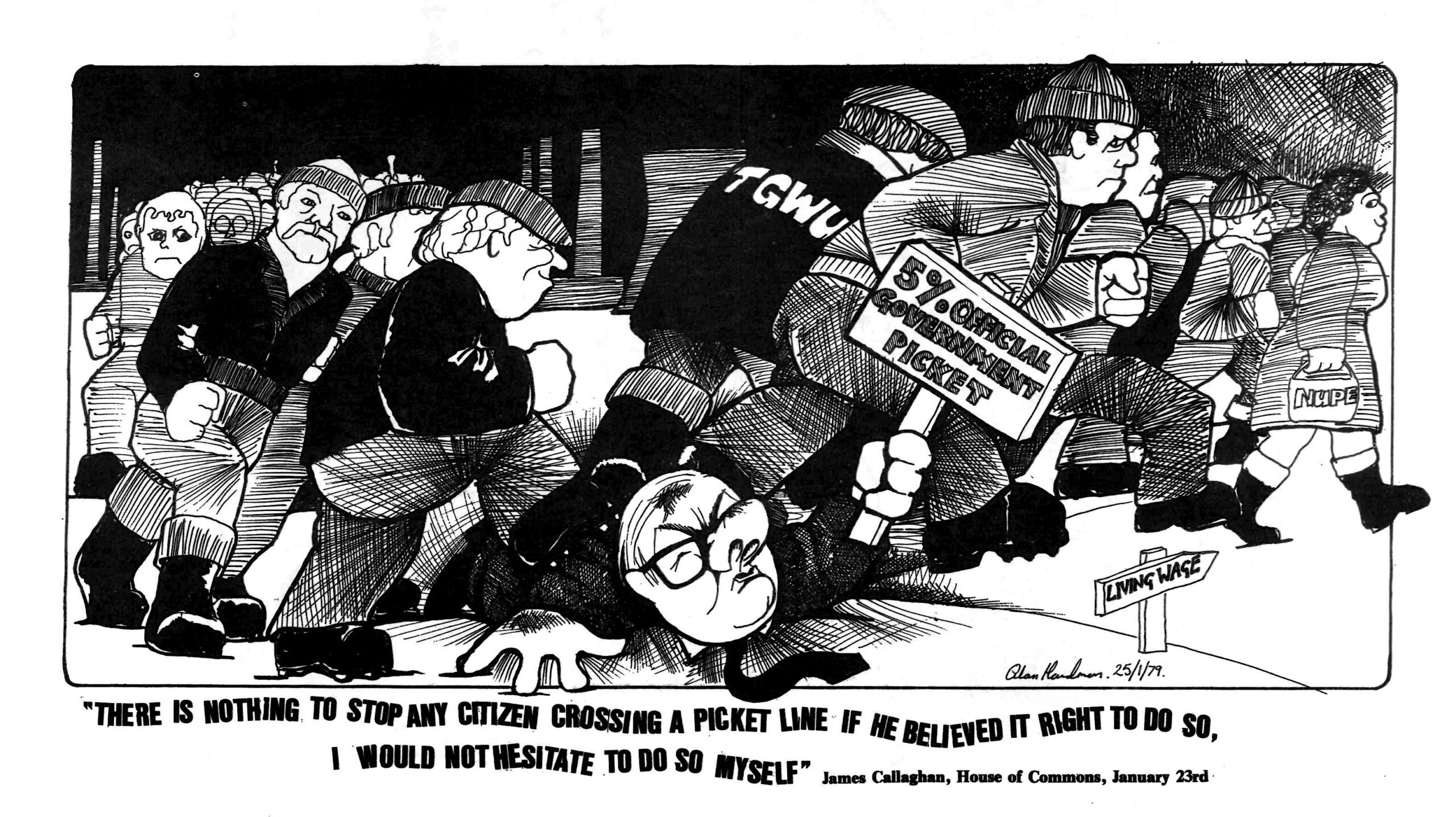

But Callaghan stepped outside of the Contract by maintaining the 5% limit beyond 1977, and by this time workers’ anger about their pay was mounting.

In 1978, Ford motor company offered a 5% rise to their workers, who responded with an unofficial walkout of 15,000 TGWU (forerunner of Unite) members. Within a few weeks this strike was made official, by which time it was 57,000 strong!

Political opposition

Industrial opposition to the Social Contract was giving rise to political opposition. Around the same time as the Ford’s strike was starting, the Labour Party conference was taking place in Blackpool.

A Labour Party Young Socialist member, Terry Duffy, delegate from Liverpool Wavertree constituency and a supporter of the Militant Tendency, (forerunner of the Socialist Party), proposed a motion calling for an end to government interference in wage negotiations.

Terry had proposed this motion at his Young Socialist branch, moved it on their behalf at the Constituency Labour Party, and was now moving it at Labour’s annual conference.

The conference was then a more democratic, policy-determining body – a far cry from the structures and operation of the Labour Party introduced in the Blair years and still, unfortunately, largely in place today.

The motion was carried by 4,017,000 votes to 1,924,000 votes, an impressive majority, the significance of which was not lost on Ford’s management.

Car workers at Vauxhall Motors had already accepted 8.5%, Ford increased its offer to 17%, which the workers accepted!

Broader political support was also ebbing away from the Callaghan government, when a string of by-elections in Labour seats were lost, forcing him into temporary parliamentary pacts with the Liberals in 1977 and even the Ulster Unionists! These deals enabled the government to survive a number of no-confidence votes.

With the Social Contract in tatters the government tried to impose sanctions on Ford and 220 other employers.But this move was defeated in the Commons.

The government survived another confidence vote, but was incapable of enforcing its pay policy.

Understandably a wave of pay demands were submitted including lorry drivers and tanker drivers, forcing Callaghan to put the army on alert.

Early in January 1979 an unofficial lorry drivers’ strike began, and although tanker drivers were not involved, they told the lorry drivers their destinations, so that flying pickets prevented petrol deliveries. Filling stations closed, and pickets were mounted at the main ports.

At the end of January, lorry drivers in the South West accepted an arbitrated rise of 20%, only marginally less than their demands. This became the standard for settlements after that.

What crisis?

Callaghan was at a four-nation summit in Guadeloupe, and held a press conference at Heathrow airport on his return.

In response to a question, he denied that there was “mounting chaos”, and the next day the Sun newspaper ran the headline: “Crisis? What Crisis”, which although a complete fabrication by that archetypal example of the gutter press, this phrase has now passed into common recollection.

The baton of fighting pay caps was passed from the private to the public sector trade unions, as rail unions ASLEF and NUR (now the RMT), on the then state-run British Rail went on strike.

Ambulance drivers soon joined them, with emergencies being taken to hospitals by army ambulances. Half the hospitals in the country were taking only emergency operations as a result of the actions of the ambulance drivers and ancillary workers. Civil servants joined in, successfully securing an above-inflation pay award.

One headline-grabbing incident was when grave diggers in Liverpool and Tameside (Greater Manchester)also went on strike.

Refuse collectors struck up and down the country, creating huge mounds of rubbish in public parks.

On 21 February local authority workers were awarded 11% plus £1 a week, with the promise of more in a comparability study which was to be conducted.

Camden council in north London paid the claim of their workers in full, and the District Auditor deemed them to be in breach of their fiduciary duty! However, unlike their socialist councillor counterparts in Liverpool six years later, no punitive surcharges were imposed on them!

Eventually the government and the TUC were able to fudge an agreement, but it was meaningless in the face of the events described above.

The strikes demonstrated a movement beyond the control of the TUC, which saw its role to defend the Labour government at all costs, despite what TUC members wanted or thought.

In March the government finally lost a confidence vote in the commons, and the Tories, led by Margaret Thatcher, capitalised on workers’ widespread disillusionment with right-wing Labour and won the subsequent general election in May 1979.

The organised workers’ movement had demonstrated its industrial power in the Winter of Discontent. But the right-wing leadership of the TUC and the Labour Party had attempted to place the working class in a political straightjacket.

This contradiction was fought out between left and right with intensity inside Labour and the unions in the 1980s, and it still casts a long shadow down to today’s class struggles.

Roger Bannister led an all-out strike of social workers during the Winter of Discontent, from November 1978 to April 1979, against the right-wing Labour council in Knowsley, Merseyside.