Scott Jones, Tower Hamlets Socialist Party

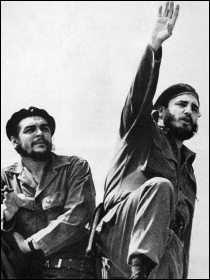

Sixty years ago in January 1959, the Cuban capital Havana erupted in celebration. Crowds greeted the victory march from Santa Clara of revolutionaries led by Che Guevara and the brothers Fidel and Raúl Castro.

The Battle of Santa Clara and the march to Havana marked the end of heroic years of struggle by the ’26th of July Movement’, with the support of Cuban workers and peasants, against US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista. His government had ruled the country with an iron fist – facilitating exploitation by US capitalism and smashing opposition and workers’ movements.

The Cuban revolution is one of the great, historic hammer blows to capitalism. It ushered in widespread nationalisation of private industry, property and land, as well as huge advances in the day-to-day lives of the Cuban people – gains which largely last to this very day.

These social gains include free healthcare and education. In both fields the achievements are impressive. A literacy campaign was undertaken, raising the national literacy rate from 60% in 1959 to 96% in 1961. Life expectancy is now almost two decades longer than in 1959 and infant mortality is lower than the United States.

There are now fifteen times more doctors since the revolution, with the best doctor to patient ratio in the world. Tens of thousands of Cuban doctors and nurses have also worked overseas in over 40 countries.

In an admirable display of internationalism, Cuba sent thousands of troops to Angola and Namibia to fight a South African apartheid army and free the countries from its rule.

Cuba rightly has the support and sympathy of workers and young people around the world. These gains and actions, and the many more that have been achieved, give an idea of what is possible by breaking with capitalism. They hint at what could be achieved under a socialist planned economy under democratic workers’ control.

The working class

Four decades prior to the Cuban revolution the greatest event in human history to date took place in Russia as the workers, under the leadership of the Bolshevik party, took power. The revolution in Cuba took a different route.

The leader of the revolution and future leader of Cuba, Fidel Castro, while exiled in Mexico following the defeat of an earlier uprising on 26 July 1953, gathered a small force of 82 men who landed in Cuba aboard a boat called Granma in 1956.

The group gradually built up their forces and waged a guerrilla war against the government with the support of peasants and workers, successfully defeating Batista and forcing him to flee the country in 1959.

Unlike Russia in 1917, the working class did not play a central role in the revolution, forming democratic bodies like soviets. The central role of the working class in a revolution is vital. Also, unlike Russia, there was an absence of a revolutionary party like the Bolsheviks.

In Cuba, the Communist Party was formed after the revolution and the Cuban workers and peasants had no direct say in the programme and policy of the new Cuban state.

Through a combination of the pressure of the Cuban masses and hostility from US imperialism, terrified as it was of ‘socialism on its doorstep’, the new Cuban government nationalised most of the economy. This included all the major industries and much of the private property owned by US capitalists and, in some cases, organised crime. The hostility went as far as supporting armed intervention in 1961, in the Bay of Pigs invasion, as well as subsequent terrorist attacks carried out by the CIA and right-wing Cuban exiles.

It was through this process that Cuba established a planned economy which made all the economic and social gains possible.

But the opposition of the United States and its ruthless economic embargo (still in place today and estimated to have cost Cuba $1 trillion) led Cuba towards the other world power of the time – the Soviet Union which had, under Stalin and his successors, deteriorated into a bureaucratic regime. Its influence, combined with the absence of genuine workers’ democracy, meant the planned economy developed into a top-down bureaucratic model similar to the deformed workers’ states in eastern Europe and the Soviet Union itself.

The programme of the Socialist Party and the Committee for a Workers’ International is one of nationally, regionally and locally – at every level – elected representatives being accountable and subject to instant recall. We call for these elected representatives to receive only the average wage of the workers.

Leon Trotsky, one of the leaders of the Russian Revolution and whose writings much of our programme is based on, explained that a “nationalised planned economy needs democracy as the human body needs oxygen”.

In Cuba, Che Guevara, always principled and self-sacrificing, refused to take a wage at all. Most other officials took average wages and refused any perks. And Cuba hasn’t ever taken on the same horrific character of Stalin’s Russia.

In fact, on one occasion Che described the regime in Russia as “horse shit”! But without the key workplace and political democracy outlined, there developed a top-down society where, despite regular referendums being held, everything starts and ends with the government. It is this which has held Cuba back from making even more gains for workers. Particularly since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990, this has left it open to attack and exploitation again by capitalism.

‘The sun goes out’

Fidel Castro described the collapse of the Soviet Union in early 90s as the “sun going out” and it forced Cuba into what became known as the ‘special period’, which in reality meant austerity measures, as the vast resources and funds channelled to Cuba from Russia dried up.

It is testament to the support for Cuba’s revolutionary gains, and the determination to keep them, that Cuba’s planned economy survived this period.

As we have written in the Socialist previously, Cuba defied the laws of political gravity, despite the tidal wave of free-market capitalism which dominated the world economy. The regime was also able to sustain itself through links with Hugo Chavez and his left government in Venezuela, which provided Cuba with cheap oil.

In fact the revolutionary movements that swept Latin America throughout 2000s – like in Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador – offered Cuba an opportunity to break out of its isolation and to also build a socialist federation in the region, which genuine workers’ democracies would have done. But these movements and governments didn’t break with capitalism or go as far as the Cuban revolution. They failed to learn any of its lessons.

The fate of these governments also shows that the lessons of the Russian revolution – the participation of the working class, the need for workers’ democracy and the role of a revolutionary party – are as vital as ever.

Despite all the colossal outside influences which have buffeted Cuba, change in the country itself has been slow. Fidel Castro, effectively Cuban leader since 1959, stepped down in 2008 (passing away in 2016), to be succeeded by his brother Raúl who himself stepped down in 2018.

In the economy, the regime has introduced incremental steps towards capitalist restoration, opening up certain sectors to private ownership – especially small and medium-sized businesses. 500,000 licenses have been issued to ‘cuentapropistas’.

Tourism has continued to grow for years and other foreign investment has taken place, such as plans to open one of the largest docks in Latin America in the west of Cuba – all funded and owned by Chinese capital for the purpose of profit.

Another $3 billion a year has come into the island from abroad, sent to relatives by Cuban émigrés.

And cracks are showing in some of the state-owned sectors, particularly transport, which has been hit hard by the collapse of the Venezuelan economy and the turning off of the oil taps.

New Cuban president Miguel Díaz-Canel has replaced Cuba’s transport and finance ministers and its national airline suffered a deadly crash as 112 were killed at Havana’s José Martí International Airport on a plane operated on behalf of Cubana de Aviación on 18 May 2018.

While the US embargo remains in place there were historic moves made by the Obama presidency to reopen diplomatic and travel links with Cuba in 2014, representing a seismic shift in US policy, however some of these moves have been scaled back under Donald Trump who has returned to hostile rhetoric of the past. Recent US policy towards Cuba reflects how the transition to capitalism in Cuba will not be a straightforward, uninterrupted process.

Support for the gains of revolution in Cuba remains high and the dismal failure of capitalism in Latin America, the US and the Caribbean itself – particularly the horrendous example of US-controlled Puerto Rico – will have an effect.

But it’s also true many younger Cubans are desperate to have the right to travel, as well as access to the internet and other goods. But while it might give Cubans access to cheaper consumer goods on the one hand, capitalist restoration will take away the gains of the revolution on the other.

For socialists and working-class people a restoration of capitalism would be a backwards step. It would be a disaster for the living standards of the Cuban masses. And it would be used internationally by the capitalist system and its defenders to discredit the Cuban revolution and socialism in general.

Crossroads

Cuba is a country at a crossroads. Both the pride in the remarkable revolutionary past and the problems and threats of the present can be seen when visiting the country.

The need to oppose and build an alternative to the increasing threat of capitalist restoration, and to fight for genuine workers’ democracy and a socialist planned economy in Cuba, is more urgent that ever.

This movement, defending the gains and winning new ones, fighting alongside the working class and youth who are increasingly moving into action in Latin America and internationally, could build a real socialist alternative to capitalism. And this movement, taking inspiration from the Cuban revolution, while learning its lessons, can win.