Claire Doyle, Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI)

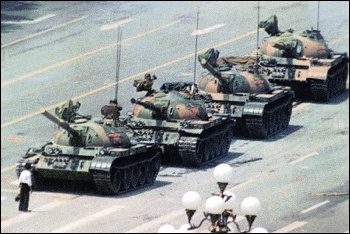

Days before the 30th anniversary of the 3-4 June 1989 massacre of hundreds, possibly thousands, of unarmed demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China’s defence minister, general Wei Fenghe maintained that the crackdown was absolutely justified!

“That incident”, he said, “was a political turbulence and the central government took measures to stop the turbulence which is a correct policy.”

The events of May-June 1989 in China constitute a dramatic and horrific illustration of the lengths to which a ruling clique will go to maintain its rule and privileges.

It was 40 years since Mao Zedong at the head of the People’s Army had presided over the wiping out of capitalism and landlordism from that vast country in what Marxists describe as the ‘second greatest event in world history’ after the October 1917 Russian revolution.

But by 1989 a mass movement was developing from below and beginning to take the form of a political revolution against the Maoist dictatorship.

From the beginning, China had been a ‘deformed workers’ state’ (a military-police dictatorship resting upon a nationalised economy), with no elements of workers’ control or workers’ democracy which provide the vital ‘oxygen’ for developing the elements of a democratic workers’ state.

Without it, as in the Soviet Union after the rise of Stalin, the ruling clique would zig-zag from one way of running the economy to another – centralisation, decentralisation and back.

This included the ‘Great Leap Forward’ begun in 1958 (which failed to industrialise and led to widespread famine) and the infamous ‘cultural revolution’ of Mao in 1966 (a bloody factional struggle within the regime) in which hundreds of thousands of talented youth and workers perished.

By the spring of 1989 – 13 years after Mao’s death – students, some inspired by the ‘reformer’ Hu Yaobang, began to challenge the ruling elite under Deng Xiaoping.

Their demands were simple and modest such as freedom of the press, freedom of speech, free elections, freedom of organisation and so forth. But they challenged the control and privileges of the so-called Communist Party that ran the ‘People’s Republic of China’.

Aims

There were, and still are, varying opinions as to whether the aims of the protests were to move towards market capitalism and the so-called democracy of the US and other major capitalist countries, or to try and take control of the economy and the state into the hands of democratically elected representatives of the working people – a ‘political revolution’.

Before the end of 1989, that very same question was posed across the whole of the Soviet Union and eastern Europe.

As in all revolutionary movements, in China in April and May of that historic year, there was a profusion of ideas and theories as to what was needed, including a political revolution.

What was lacking was any party, even in embryo, with leaders who had a clear idea of how workers and young people could channel that revolutionary energy into overthrowing the old regime.

As in Hungary 1956 or elsewhere, a revolution can begin without a revolutionary party, and go nine-tenths of the way towards victory. Workers and young people were prepared to fight to the end – to the extent of sacrificing their lives.

In these conditions a revolutionary party can be rapidly built. But without it, and without elected fighting bodies like the soviets, the most favourable situations can turn into their opposite and a whole period of reaction can ensue.

Whatever the aims of the participants were in 1989, it is clear that the eruption of a mass movement in the capital city and in towns and cities across China was threatening the dictatorial rule of the Communist Party bureaucrats in Beijing.

A sure sign of the revolutionary nature of the upheaval was the participation of school students as well as university students. The wind of revolution was blowing the tops of the trees first. The Guardian says millions “including police, judges and naval officers” were drawn in, “prompted by anger at corruption and inflation, but also the hunger for reform and liberty” (1 June 2019).

Once workers began to lend support to the student protests and take action, and the forces of the state began to refuse orders, the murderous suppression of the uprising began.

Strikes

Both before and after the massacre in Tiananmen Square, there were mass protests in hundreds of cities across the country. According to leaked government documents collected together in the ‘Tiananmen Papers’, protests were reported in 341 Chinese cities between April and June 1989.

According to Wikipedia: “After order was restored in Beijing on 4 June, protests of varying scales continued in some 80 other Chinese cities… In Shanghai, students marched on the streets on 5 June and erected roadblocks on major thoroughfares. Factory workers went on a general strike and took to the streets as well; railway traffic was also blocked. Public transport was suspended and prevented people from getting to work.” The protests in Shanghai continued for more than a week.

The authorities carried out mass arrests. They saw the threat from workers taking action as more of a threat to their future than students; many were reported to have been summarily tried and executed.

Students and university staff involved were permanently politically stigmatised and many were never employed again.

Many Asian countries’ political leaders remained silent throughout the protests. The government of India did not want to jeopardise a thaw in relations with China.

The Stalinist governments of Cuba, Czechoslovakia and East Germany, fearing similar uprisings at home, denounced the protests. Chinese students demonstrated in many cities in Europe, America, the Middle East and Asia.

After these events, the bureaucracy moved in a more pro-capitalist restoration direction. This led to a hybrid, state capitalism. It is this regime which has moved again to clamp-down on all protest and exert mass repression.

China today

So what of the situation today? The Chinese economy is more than 30 times larger than it was in 1989. The Economist points out that in the late 1980s, in nominal terms, Soviet-American trade was $2 billion a year. Now, trade between America and China is more than $2 billion a day!

In June 1989, the US President, George H W Bush wrote to Deng Xiaoping urging joint efforts to ensure the “tragic recent events” would not harm relations.

Today, notwithstanding Trump’s tariff hikes, US/Chinese trade is booming. More cars are sold by US car giant General Motors in China than in the US. China vies with the US in terms of economic and military superiority but the Economist points to the dilemma of trade relations not being quarantined from “hard questions about whether countries are partners, rivals or foes”.

Philip Stevens in the Financial Times commented on 17 May that China is seen in the US “not just as a dangerous economic competitor but a looming existential threat. Beijing may not have the same ideological ambitions as the Soviet Union, but it does threaten US primacy.”

Ma Jian, the author of a book called ‘Beijing Coma’ and a democracy activist in 1989 writes: “Within months of the Tiananmen massacre, world leaders were rushing back to Beijing to do deals, claiming that collaboration would help bring about change.” And, “as the terror of Tiananmen is being re-enacted in the gulags of Tibet and Xinjiang, western leaders shake hands with President Xi and look the other way” (Guardian Review 1 June 2019).

A Guardian editorial says: “The silence which began at home is spreading, as shown by the muted reaction to another crime against human rights unfolding in China today. An estimated one million Uighurs and other Muslims are incarcerated in detention camps in Xinjiang and forced to undergo political indoctrination…”

Despairingly, it further comments: “The build-up of the mammoth domestic security apparatus makes a mass movement in the manner of 1989 impossible”. But even this journal of the liberal bourgeoisie adds: “The unexpected and implausible does happen”!

Capitalism

Living standards in China have undoubtedly improved and huge modern industries have developed rapidly. But the regime under Xi Jinping is, if anything, more monolithic than previous ones.

Inside China there has been no straight line development towards the establishment of fully capitalist relations. The collapse of Stalinism and the capitalist ‘shock therapy’ treatment that plunged the economies of the former Soviet Union into crisis in the early 1990s stayed the hands of the Chinese bureaucracy.

So too, probably, did the news of the fate of the ‘communist’ generals in Russia who tried to recover their power in the August 1991 coup (which lasted less than three days!).

Today, there still is a very large element of state ownership and state control in the now massive Chinese economy. The proportions zig-zag. For example, telecom giant Huawei is 99% owned by its ‘trade union’ which, of course, is controlled by the state bureaucracy. Consequently, the CWI describes the Chinese economy as a ‘special form of state capitalism’.

The Financial Times quotes analysts who argue that the ‘Communist’ party “controls levers Trump can only dream of”.

The Economist bemoans the fact that any US-China trade deal will do little “to shift China’s model away from state capitalism. Its vast subsidies for producers will survive.”

Xi Jinping is a dictator and part of a very rich elite. But he still uses Marxist and Maoist phraseology as a cover for autocracy, while viciously repressing opposition and all democratic rights.

At a time when the world’s economic and political relations are in turmoil, and capitalist austerity and super-exploitation reach new depths, explosions of anger from below can break out in almost any country and take on unexpected dimensions.

The Chinese regime knows only too well that lessons drawn from the past can lead on to more successful challenges to their power in the future. This is what lies behind their pervasive censorship of all media and a total ban on any mention of 3-4 June.

The CWI will strive to reach ever wider layers of workers and young people in China and throughout Asia in order to build the forces necessary to win real and lasting victories on the way to establishing a socialist world.