Lessons from history

Class collaboration and worker militancy in World War Two Britain

In the second of a series of articles on ‘war, global crises and working class struggle’, Alec Thraves – Socialist Party national committee – explains how workers’ militancy broke the shackles of the World War Two coalition government in Britain

The horrific coronavirus crisis has seen international capitalist leaders, like US president Donald Trump and Prime Minister Boris Johnson, comparing this unprecedented modern-day disaster to wartime conditions – which therefore require exceptional emergency measures and enormous personal sacrifices, especially from the working class!

But as in past wartime conditions, the primary role of these political bag carriers of big business is to protect and preserve their capitalist system, by any means necessary, so that when conditions return to some kind of normality their grotesque profits can continue to roll in.

The experience of World War Two exemplifies the methods and measures capitalism adopts during serious crises.

Typically, the full resources of the capitalist state to control society are utilised. These include integrating and cooperating with traditional political adversaries in the leadership of the labour and trade union movement, and crucially, concealing from the working class the responsibility of their system for such devastation.

The capitalist class successfully portrayed World War Two as a ‘peoples war’ against fascism, concealing the underlying imperialist struggle for world market domination.

In 1940, when Tory Prime Minister Winston Churchill invited Labour to participate as a full partner in his wartime coalition government, it represented the start of a period of class collaboration with the Tories that lasted five long years.

Churchill recognised that in order to dampen any opposition and retain working-class support for the draconian measures necessary to pursue the ‘war effort’, he needed to attract the endorsement of the trade union movement from the very outset.

Ernest Bevin, right-wing, anti-communist general secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers Union (T&G, now Unite) fitted the role perfectly, and he was given the job as Minister of Labour and National Service (1940-45).

With Bevin on board the coalition pushed through the ‘Emergency Powers Act and Defence Regulations’ (the Act was finally repealed in 1959!) giving it the right to direct and control all labour. This was followed by ‘Essential Work’ legislation in 1941 allowing the ‘dilution’ of labour (ie using unskilled or semi-skilled workers in traditionally skilled occupations), and the direction of skilled workers to wherever they were most needed. Strikes and lockouts were also banned.

However, Churchill’s political coup of bringing Bevin into government didn’t prevent industrial action from taking place.

In fact, there were numerous disputes and strikes in defence of wages, conditions, health and safety, and opposition to unscrupulous employers who were taking advantage of government legislation to further boost their profits.

Even in Bevin’s own T&G backyard, and much to his embarrassment, two major disputes erupted in 1943. One involved 12,000 bus workers, and the other was on the Liverpool Docks.

Despite the legal ban on strikes, and Bevin’s renowned conciliatory approach, there were over 900 illegal strikes in the first few months of the war, and the number of strikes increased each year until 1944.

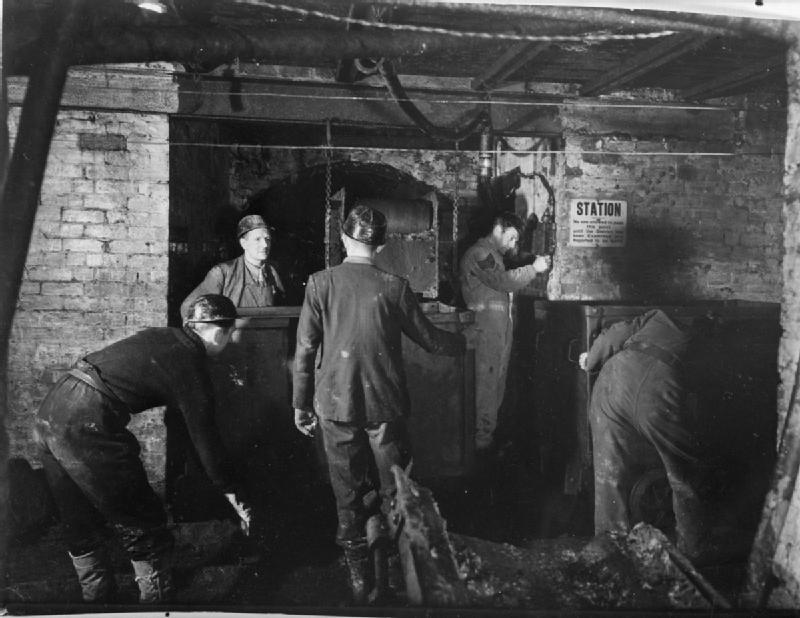

The Minister of Labour introduced conscription for the mines to help increase coal production, and 48,000 ‘Bevin Boys’ (young workers drawn from other industries*), as they became known, joined the half a million miners who, despite their crucial role, were seeing their wages falling behind other workers during the war.

Not only were miners prepared to strike for better pay, against the wishes of their Miners’ Federation leaders, but they were also demanding nationalisation of the pits and no return of the coal owners after the war!

It took unofficial, illegal strike action to win their wage demands.

120,000 miners on strike in Yorkshire, 100,000 in Wales, several thousand across Lancashire, Staffordshire, Durham and Scotland, achieved in militant action what their ‘leaders’ failed to achieve through negotiations.

Trade union membership increased by three million during the war to around seven and a half million by 1946, alongside a big growth in the number of shop stewards committees established to fight local battles, and to counteract the dead weight of the full-time trade union officialdom.

State exposed

The role of the capitalist state in using emergency legislation to attack democratic rights and curb trade union action was even more exposed in 1944.

At the peak of wartime strike action, legislation was introduced, supported by the Trade Union Congress (the umbrella organisation of the trade unions), that made ‘incitement’ to strike unlawful. But in that year there were over 2,000 stoppages and the loss of nearly 4 million days of production.

The attempt to stop ‘outside agitators’ inciting workers to strike was allegedly aimed at Communists, and particularly Trotskyists, but was treated with the contempt it deserved. This was especially the case among industrial militants in the essential services of coal mining, docks and wartime manufacturing who had more than enough of their own agitators!

Those commentators who applauded Labour’s class collaboration with the Tories, and particularly Bevin’s role as a minister, ignore the vital importance of the trade unions being independent and separate from the state.

Any concessions made by Churchill during Bevin’s ministerial portfolio weren’t due to Bevin’s belligerent character or his trade union negotiating skills. They were because of the fear of the ruling class that rank-and-file trade unionists, and the working class generally, would start to recognise the real reasons for the war, and start searching for an alternative – ultimately a socialist alternative.

Yes, the roots of the first majority Labour government 1945-1951 were to be found during World War Two and the foundations of the welfare state stemmed from that period. But it was the desire of the returning troops and their families at home for a better life, a true ‘land fit for heroes’, and the potential for revolutionary struggle to achieve those aims, that dragged those reforms out of the ruling class.

The superiority of centralised planning of the economy and services instead of the chaos of the neoliberal market; public ownership and nationalisation instead of private ownership and greed; democratic rights and equality instead of draconian laws and oppression; that was the real fear of the ruling classes.

But those alternatives are only possible in the long term if the means of production and distribution are owned and controlled democratically by the working class.

If not, then temporary gains, such as those that were made after World War Two will, as we have witnessed, be privatised on the altar of privilege and profit yet again.

Nye Bevan, the left-wing Labour MP – a thorn in the side of Ernest Bevin – challenged the minister towards the end of the war to explain how his public commitment to full employment could be solved without the ‘transfer of economic power’. Bevan received no reply from Churchill’s minister!

There was no ‘going back to normal’ for the working class after World War Two. And with the collaboration of the Labour and trade union leaders, economic concessions from the ruling class and the absence of genuine, mass revolutionary parties internationally, then imperialism and Stalinism derailed a potentially historic movement.

For a new generation of socialists many lessons will be learnt from this period so that mistakes are not repeated and socialism becomes the future to end all wars and capitalist crisis!

- It was more dangerous working in the coal mines than being in the armed forces. One-third of Bevin Boys were either maimed or killed during the first year! In 1944, with the assistance of Trotskyists (forerunners of the Socialist Party) and rank-and-file Communists (Communist Party leaders were collaborating with the government), apprentices organised and took successful strike action, especially in the North West, North East, and Yorkshire, against conscription into the mines.