World economy

Bosses’ crisis, workers pay

Build a socialist alternative

|

|

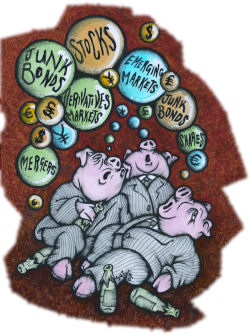

Bubbles: Socialism Today, May 2007, cartoon, photo Suz |

The global economy is in deep trouble. When the subprime mortgage crisis hit financial markets in August, it was dismissed by city pundits as a mere hiccup that would be quickly overcome. But the long queues outside Northern Rock building society were a symptom of worse things to come.

Lynn Walsh

The president of the speculative, private equity firm, Blackstone, recently said: “The subprime black hole is appearing deeper, darker and scarier than they thought.” The credit crunch is biting more and more on the wider economy, threatening the United States, Britain, Europe and elsewhere with economic recession.

Some of the world’s biggest banks and finance houses have been hit by massive losses, the result of their reckless speculation in the US high-risk mortgage market, the so-called subprime sector. Reported losses already total around $60 billion. But that is peanuts compared to the estimate of the Royal Bank of Scotland: “This credit crisis, when all is out, will see $250 billion to $500 billion of losses”.

‘So what?’ some may say. ‘Some of the super-rich speculators are getting their comeuppance. They deserve to have their fingers burned.’ And it’s true, the banks and hedge funds which speculated in risky mortgage bonds deserve all they get. But after all their losses, the bank chiefs and hedge fund managers are still going to be super-rich.

For instance, the mighty Citibank has recently announced subprime losses of $11 billion. Yet the chief executive, ‘Chuck’ Prince, has walked away with a $40 million (£19 million) pay-off, together with perks like a personal assistant, a chauffeur, etc, etc. Stan O’Neal, chief of investment bank Merrill Lynch, has just received a pay-off of $161 million after presiding over subprime losses of $8.4 billion!

The problem is that the banks’ huge losses will, as time goes on, impact on working people. Through the investment banks, many pension funds and insurance companies have invested in toxic subprime mortgages. When the losses work through, they will inevitably cut the value of workers’ pensions. Some funds could go bust.

The situation was summed up well in the London Evening Standard (9 November). Under the headline “Joe public will pick up tab for subprime”, Anthony Hilton wrote: “It is pretty much the golden rule of financial markets that when there are losses to be borne, they should fall on the public, not on the professionals”.

When Northern Rock began to sink, for instance, the Bank of England and the government stepped in with £35 billion of taxpayers’ money to rescue the directors from their greedy, short-sighted policies. But it is not only the risky, subprime loans that are causing problems.

Because of the house-price bubble and the huge burden of mortgage debt this has created, the number of repossessions in England and Wales is escalating. Around 14,000 homes were repossessed in the first half of 2007, compared with 10,800 in the first half of 2006.

Banks and other money lenders have pushed people to take on more and more debt to boost their spending power. This is becoming unsustainable for increasing numbers of people.

The president of the debt collectors’ association, currently pursuing over £21 billion of bad debt, recently said: “The debt collection industry has been growing rapidly in the past year. It is being driven by the underlying credit boom, but the crisis in financial markets has made the situation worse.” (Financial Times, 13 November)

As the warnings now in the financial pages of the main newspapers are borne out, the majority of people in society – rather than the super-rich minority – will increasingly be forced to bear the consequences. Working people must fight against this system, capitalism, that periodically off loads its crises onto their backs, and build a socialist alternative.