The Socialist’s series on the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution

April 1917: how the Bolsheviks reorientated

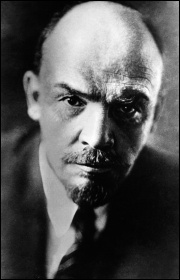

Vladimir Lenin, one of the central leaders of the 1917 Russian revolution, photo German Federal Archive (Creative Commons) (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

Paula Mitchell, Socialist Party executive committee

On 3 April 1917, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin returned to Russia from exile. Lenin’s arrival turned the Bolshevik party upside down and changed the course of history.

Just weeks earlier, demanding an end to the bloody slaughter of World War One, the masses of working class and poor in Russia had risen up in a revolution and driven out the Tsar and government.

But they were not yet conscious of their own power or of what to do. While Bolshevik members were in the workplaces and streets alongside their fellow workers making the revolution, the leaders of the party were still, by necessity, in exile.

Within days of the euphoria of sweeping aside the old regime, instead of the working class and poor taking power themselves, a situation of ‘dual power’ arose.

Capitalist parties stepped into the vacuum to establish a provisional government – not in order to take the revolution forward in the interests of the majority of the population, but in order to look after their own interests.

Workers’ councils – soviets – had arisen in the revolution, and the two main parties that won the leadership were the Mensheviks (the original minority of the workers’ movement in Russia) and Social Revolutionaries (a party based on the middle class in the towns and peasants in the countryside).

Even though the Soviets had majority support, the Menshevik and Social Revolutionary soviet leaders voluntarily handed power over to the capitalist provisional government. This included support for the government’s continued prosecution of the World War, on the grounds that it was now, they said, a war in defence of the revolution.

Ordinary working class Bolsheviks instinctively knew this was wrong. They thought that the class which had won the victory in February should be the one that took power. But when some of the Bolshevik leaders, including Stalin, returned from exile in March, they took the Bolshevik party sharply to the right and similarly declared support for the provisional government.

Meanwhile, still in exile, desperately seeking ways to return, Lenin was urgently sending telegrams saying what needed to be done: “absolute lack of confidence; no support to the new government”.

Lenin calls for socialism

On his arrival in Russia, Lenin was greeted at the train station in Petrograd by dignitaries from the Soviets, expressing the hope that he would join them in their support for the provisional government – one naval officer even suggested he join it.

But Lenin turned away from them. Instead he addressed the thousands of workers, soldiers and sailors who had assembled to greet him. To the horror of the worthies behind him, he declared: “The Russian Revolution achieved by you has opened a new epoch. Long live the world socialist revolution!”

The next day he presented his ‘April Theses’ to the Bolshevik central committee. This short, terse document, little more than a list of bullet-points, was one of the most important of the revolution.

In it, Lenin argued that the provisional government was a capitalist government and the war was an imperialist war. The working class, leading the peasantry, should take power and begin to carry out a socialist transformation of society.

This threw the Bolshevik party into crisis and at first Lenin was in a minority of one or two.

Up till then, the view of most Marxists, following the model of the capitalist revolutions that had happened in western Europe, was that capitalist democracy needed to be established before socialism. Since there were still substantial feudal elements in Russia, they argued that the revolution had to be a capitalist democratic revolution. To the Mensheviks this meant supporting capitalist parties. Socialism was for the distant future.

After the defeat of the 1905 Russian Revolution, Trotsky had written his theory of ‘permanent revolution’. Building on the Marxist understanding of uneven and combined development, he realised that the growth of capitalism and imperialism in the west inevitably impacted on economic and social progress in other parts of the world.

The Russian capitalist class was tiny, frightened by defeat in 1905, and tied to the big landlords and imperialist powers. Most industrial development had actually been driven from the top by the Tsar in order to build up his massive military state power, was reliant on western investment and mostly foreign-owned.

This meant that it would fall to the working class and poor to carry out the tasks that the capitalists had done elsewhere – to distribute land to the peasants, bring about capitalist democracy, and establish a stable nation state.

The Bolshevik party had drawn the same conclusion, and put forward the idea that a government of ‘workers and peasants’ would be necessary to carry out the capitalist democratic revolution.

But Trotsky drew further conclusions. The peasantry – though the majority in society and the poor sections of it were extremely oppressed – was a disparate, scattered class without a collective outlook.

The working class on the other hand, though numerically smaller, had been thrown together into massive factories and had the ability to organise with a more collective consciousness. It would take a strong lead by the working class to convince the poor peasants that their interests lay with the working class, otherwise they could be pulled behind the ruling class.

Trotsky’s permanent revolution theory argued that inevitably the working class wouldn’t stop at distributing land to the peasants and democratic measures. In order to satisfy their own interests – a shorter working day, decent wages, etc – the working class would need to press on to socialist tasks, including taking over the factories and the banks. Vitally, the revolution would then have to spread internationally.

Relevant today

Egyptian revolution: Lenin said of revolutions that they demonstrate two things: that the people cannot go on being ruled in the old way. And that the rulers cannot go on ruling in the old way (Guardian Editorial, 4 February 2011)

These ideas are as relevant today as ever. The brutal, exploitative system of capitalism has created a nightmare that destroys the lives of masses of people in Syria, Iraq, Libya – killing hundreds of thousands and displacing millions, who then face an additional horrific ordeal as refugees. Starvation again ravages East Africa.

The capitalist classes in the neocolonial world are as weak and as tied to landlordism and imperialism as ever. Capitalism’s inability to improve the lives of the masses is stark.

In April 1917 Lenin came to this same position. He said the old formula of the Bolsheviks was obsolete. He argued it was dangerous to create illusions that the capitalist provisional government would end the war, or meet the demands of the peasants for land or the needs of the workers.

Instead, an independent working class position was essential. It was necessary to wage a struggle to convince the soviets to take power.

By the end of April Lenin had successfully convinced the party. Worker Bolshevik members found Lenin’s arguments made sense of their experience of the previous few months and of events as they developed every day. The truth of this was shown in the growth of the party just in those few weeks.

Lenin understood that at that stage the Bolsheviks were in a minority in the working class. They had only 1-2% of support in the soviets in February and about 4% in April.

Just as Socialist Party members do today, although of course in much more heightened circumstances in 1917, the job of the Bolsheviks was to live and fight alongside the best layers of the working class and the masses and “patiently explain”.

They developed a programme to appeal to workers, peasants and soldiers with demands and slogans – ‘bread, peace and land’.

The masses of working and poor people would learn through experience that the provisional government could give them neither peace nor land.

No dogma, living theory

None of what Lenin and Trotsky were arguing was abstract theory but was a result of real living forces and developments. There was an upsurge of workers and peasants in the next few weeks and months. Workers were struggling on their own demands – to end the war, for shorter working hours, for better pay, for bread.

Under the provisional government, very little was changing. The war continued, workers were still being sent to die. In fact, in April, foreign minister Miliukov ordered an offensive by Russian troops.

Soldiers refused to comply and masses of people demonstrated. The factories remained in the hands of the capitalist bosses, the land remained in the hands of the big landlords. Workers struck, peasants seized the land.

On the demonstrations, workers demanded “Down with Miliukov!” Some also chanted “Down with the provisional government!” While the strongest proponent of the idea that the provisional government needed to be overthrown, Lenin also understood that this was premature.

While sections of the working class were starting to draw this conclusion, the majority still had illusions in the provisional government. It was necessary to still “patiently explain”.

This serious approach, in tune with the level of understanding of the masses, working to win people over rather than issuing empty phrases, was a key reason why the Bolshevik party was able to grow, and is an essential lesson for socialists to learn today.

The truth was, as Lenin warned in April, that to attempt to stick to the Menshevik position of support for the provisional government would have meant undermining the working class. In practice it would have led to bloody counter-revolution.

The most important lesson of April 1917 is the role of a revolutionary party and of leadership. The main feature of a revolution is that the masses of the working class move centre stage and make their own history. In 1917 it was the masses that drove events. But it was the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, and the Bolshevik party, that ensured victory in October. In the course of 1917 the Bolshevik Party became a mass party, the most democratic in history.

A revolutionary party is necessary to organise, generalise, point the way forward, say what needs to be done. The working class is made up of all different kinds of people: different genders, ethnic origins, ages, levels of understanding and experience, etc. The ruling class tries to exploit these divisions – the role of a revolutionary party is to unite workers. And in that party, a leadership with authority, experience and determination is needed.

The next few months saw huge twists and turns. But by the autumn the Bolsheviks had won a majority in soviet after soviet.

The re-arming of the party in April was fundamental to the ability of the working class and poor to take power into their own hands in October 1917, to end Russia’s involvement in the murderous world war, and begin to build towards a new, socialist society.

The world today is not the same as 1917. But the gap between rich and poor around the world is greater than ever before. Even in wealthy Europe, Tory austerity, passed on by right-wing Labour councils, kills and inflicts poverty in Britain, while EU-enforced austerity drags Greek people in particular through the dirt.

A rebellion against the establishment, austerity and the rich, has begun – expressed in the Brexit vote, the rejection of the ‘lesser evil’ Hilary Clinton, the rise of left (and right) populist organisations such as Podemos in Spain, and the support for anti-austerity policies when they were espoused by Jeremy Corbyn’s election campaigns.

The lessons of the Russian Revolution are essential today. In Britain we see an attempt by liberal pro-capitalist forces to lead and shape the first shoots of rebellion against austerity by trying to bring people together behind right-wing Labour, Lib Dem and even Tory ‘leaders’.

Meanwhile in the Labour Party, instead of making a stand against Blairite pro-capitalist MPs and councillors and putting forward a clear socialist programme, the people around Jeremy Corbyn conciliate in the vain hope of achieving ‘unity’.

A clear independent working class position, boldly but “patiently” arguing a socialist alternative, is essential.

The April Theses

by VI Lenin

£2.50 including postage – cheques to ‘Socialist Books’

For more titles on the Russian Revolution and Marxist classics go to leftbooks.co.uk

PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD

020 8988 8789