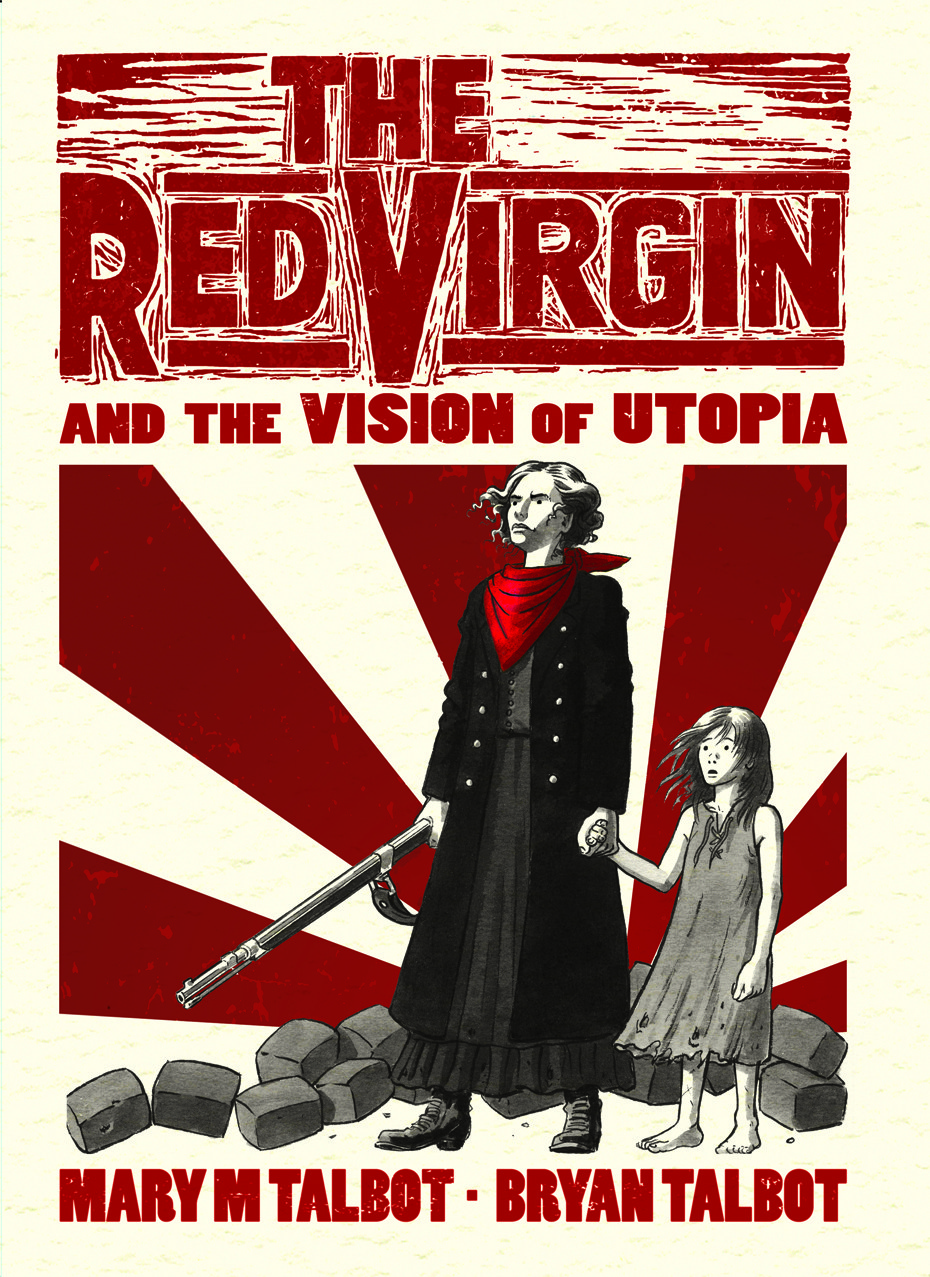

Graphic novel review: ‘The Red Virgin and the Vision of Utopia’

Vivid visual account of the Paris Commune

Iain Dalton, Leeds Socialist Party

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, there are a number of other revolutionary movements that Marxists hold as important events, which, have helped us develop our ideas. For Marx himself, none was more important than the Paris Commune of 1871, the first time workers took power.

This graphic novel strays across different periods of time, but its focus is on the commune and its aftermath. The title refers to the ‘Red Virgin of Montmartre’, Louise Michel, a revolutionary anarchist who the bulk of the story is told around.

Shortly into the story we pick up Louise among the starving masses in Montmartre, a suburb of Paris. Food shortages due to Napoleon III’s disastrous war with Prussia were fermenting mass revolt.

This exploded during peace negotiations in March 1871, when the royalist National Assembly, which replaced Napoleon, attempted to disarm the mainly working class and anti-monarchist National Guard. The Parisian masses and the National Guard revolted against this abandonment.

Within days, a commune of deputies from the districts of Paris had been elected. This took radical measures, including providing schooling for free, pawnshop amnesties, cancellation of rent arrears, and public ownership of industry.

But with the revolution confined to Paris, the capitalist counter-revolution was left free to gather its forces in Versailles, and crush the Commune in bloody fashion.

A significant portion of the tale tells of Louise’s capture, imprisonment and exile in the French Pacific colony of New Caledonia.

This section more than others illuminates her solidarity with the oppressed: Arabs deported for rising in Algeria around the same time as the Commune. And the native population, the Kanaka, which unsuccessfully rose against the French occupying authorities.

A thread running through the book is Louise’s interest in utopian fiction, which is used to illustrate the possibilities of a society freed from the domination of capitalism. It also serves as the reader’s introduction to her through the eyes of American writer Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who discusses her life with a survivor of the Commune.

Graphic novels dealing with revolutionary events and revolutionaries are becoming increasingly common, including Kate Evans’s ‘Red Rosa’ in 2015.

The combination of vivid artwork, detailed notes which give background, and narration and dialogue drawn from the subjects’ own writings and speeches, can bring to life these events, and make them accessible to a wider audience. ‘The Red Virgin’ is yet another welcome addition to this growing genre.