Lessons of struggle: If you fight, you can win!

Young people face enormous attacks on their right to a future – unemployment, low pay, ever-increasing university fees and slashed public services.

But, as the Youth Fight for Jobs campaign says, none of this is inevitable. The question of how to stop these attacks is central to building a fightback.

Here, Socialist Party activists provide a small taste of some of the past battles they have been involved in where victories were won by working and young people.

These are rich in lessons for the battles faced by this generation. Crucial is the conviction of socialists that working class people can act in their own interests and that if you fight you can win, but if you don’t you’re likely to lose.

Liverpool Council 1983 – 1987

‘Jobs for all’ is the language of socialism

Liverpool City Council rally November 1983, photo Paul Traynor

In 1984 Liverpool City council, led mainly by Militant (the Socialist Party’s predecessor), won a sensational victory over the ruthless Tory government of Margaret Thatcher.

Tony Mulhearn, one of the 47 Liverpool Labour councillors subsequently victimised by the state and witch-hunted by the Labour Party leadership, describes the achievements of that struggle 25 years ago.

The current magnificent campaign for jobs and education opportunities for youth should be welcomed enthusiastically by all sections of the labour movement. The achievements of the socialist 47 councillors in Liverpool between 1983 and 1987 stands as a concrete example of what can be gained with a fighting socialist programme.

Liverpool City Councillors hold press conference at House of Lords 26 Jan 1987, photo Dave Sinclair

On being elected in 1983, against a background of high youth unemployment, Liverpool council declared its intention of offering a future for young people. By 1985, for example, students in Liverpool had won a number of measures that would not even be dreamed of in other education authorities and now. This included funding for three full-time student union officials; increased funding for student unions; time allowed for Youth Training Scheme trainees to meet with trade union representatives during college hours; free meals, books, paper and travel tokens for the unemployed and those under 18; increases in grants and free nursery facilities in every college.

In the teeth of Liberal Democratic opposition locally and Tory opposition nationally, the following programme was carried through: 2,873 tenement flats and 1,315 walk-up flats were demolished; 4,800 houses and bungalows were built; 25 new Housing Action Areas were developed; £10 million was spent on school improvements; and five new sports centres were built. Two thousand additional jobs were provided for in the Liverpool City Council budget. As a result of these initiatives by the Liverpool 47, a total of at least ten thousand people per year were employed on the council’s capital programme.

These achievements were lauded, not only by friends of socialism, but also by Wimpey, the big building monopoly and no friend of labour or the construction trade unions. That company declared: “The contracts (initiated by the city council) have had the effect of stabilising our workforce and giving us the opportunity to offer more permanent appointments. We have been steadily increasing our level of staff over the last 18 months, the first time in many years, and also have been able to increase our intake of apprentices. It is therefore essential, having reached the level of staff and apprentices, that work is still released to enable us to carry this forward” (quoted in Liverpool City Council’s magazine Success against the Odds).

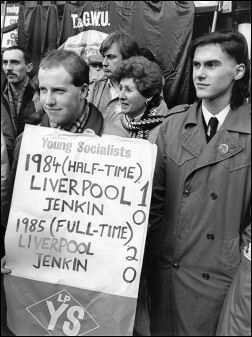

Liverpool City Council: Celebrating the climb down of government minister Patrick Jenkin, granting Liverpool City Council more money, photo John Smith

In addition, the council had introduced nomination rights which allowed local authority trade unions to nominate job applications for council vacancies. This guaranteed fairness in the interview process and enabled unemployed youth to be targeted. Naturally this was attacked by the Liberal Democratic/Tory alliance as being ‘jobs for the boys’. This charge came from a party who later employed a Liberal party official as an adviser to the Liberal leader, at council taxpayers’ expense,

A worker commented in an article in the Liverpool Echo that under the previous Liberal-Tory council “security men were working 100-120 hours a week for 50 pence an hour. I think Derek Hatton [deputy leader of the Militant-led council] and his colleagues should be praised not attacked… this council has given us dignity and self respect by changing our name to static security and giving us uniforms, giving us a 39-hour week and doubling the labour force.”

The 47 also increased the numbers employed in education: from 16,317 in June 1982 to 16,836 in June 1986 – an increase of 519. Liverpool exceeded the statutory limits laid down by Tory education ministers for the numbers employed in education.

To the charge that the money isn’t available to implement such an ambitious programme, the 47 answered: the capitalists have the wealth locked up in the banks and financial institutions. Let them pay. Today, we argue the same, but more emphatically.

If all councils nationally had replicated the actions of the Liverpool 47, unemployment, particularly youth unemployment, and its related social problems would have been dealt a massive blow.

The Liverpool City Council of the 1980s is a beacon that can inspire the Youth Fight for Jobs campaign to even greater heights.

See Liverpool – A city that dared to fight by Peter Taaffe and Tony Mulhearn

Organising mass action against the Poll Tax

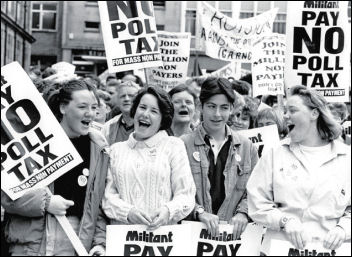

The battle against the poll tax in 1990-91 was one of the biggest mass movements in Britain of recent decades. Steve Score, an anti-poll tax activist, describes how 14 million people defied the law and the Tory government by refusing to pay and how this movement forced the scrapping of the tax within four years, and ultimately brought the downfall of its chief architect – Margaret Thatcher.

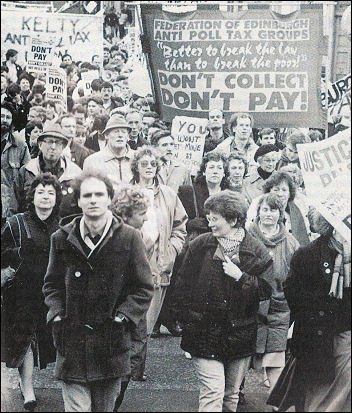

Thatcher was defeated on the issue of the poll tax, photo Militant

The poll tax was a standard charge on rich and poor alike and was levied on each individual over the age of 18 including the unemployed, students and those with no personal income at all who had been exempt from the poll tax’s precursors, the rates. In fact a rich person living in a rural area could end up paying far less that a poor family in a city.

Led by Militant, mass non-payment was built by community based anti-poll tax unions in cities, towns and villages across the country, including on many housing estates and in many workplaces. These were linked up locally and nationally into the Anti-Poll Tax Federation and actively involved huge numbers of people.

Militant predicted the anger the tax would cause, and saw that, because it hit everyone together, there was huge potential to build a mass movement. The trades union leaders and the Labour Party leadership opposed it verbally, but did nothing to fight it, actively opposing the non-payment campaign. Labour councils, despite calls for them not to collect it or comply with it, ultimately went the whole way and sent bailiffs into working-class people’s homes to impound their property and jailed people for not being able to pay.

It was introduced in Scotland a year earlier than in England and Wales; perhaps because the Tories had so little support there that they felt free to experiment! But it ignited the anger of Scottish workers, and the method of mass non-payment was tested out.

Militant supporters had to argue against those who said mass non-payment wouldn’t work, or would only get working-class people in debt. Some advocated non-payment only for a few prominent individuals who ‘could afford it’. On the contrary, only a mass movement would work. In fact millions would not be able to afford it and we planned to unite the ‘can’t payers’ with the ‘won’t payers’. That way an organised campaign could defend people from the threatened sanctions of wage and benefit deductions, property seizures and jailing.

Mass non-payment

The Battle to defeat the poll tax, photo Steve Gardiner

Mass demonstrations developed around the rate-setting council meetings. On 31 March 1990, the day before the poll tax was introduced in England and Wales, massive demonstrations were held simultaneously in London and Glasgow involving a quarter of a million people. When the London demonstration reached Trafalgar Square, police actions provoked a big battle which became known as the ‘poll tax riots’.

Some claim it was these big demos which beat the poll tax. They were important, but it was organised mass non-payment over years which was the real reason for its demise. We worked out a detailed strategy, keeping the confidence of the movement up by discussing and answering every question on the strategy in meetings and in millions of leaflets.

We clogged up the courts by mobilising non-payers to attend their hearings and assisted people by asking questions in court. Court rooms were unable to cope.

We mobilised to stop the bailiffs from seizing property. In Scotland, where powers were different, communities organised to blockade estates where ‘warrant sales’ were threatened. In England and Wales we also organised on estates against the bailiffs. Above all we made people aware that, despite attempted intimidation, the bailiffs do not have the power to force their way into homes if they are not let in.

We also organised to stop poll tax jailings – the ultimate sanction. Hundreds of people were sent to jail, including many Militant supporters. Terry Fields, a Liverpool MP and Militant supporter, was sent down for standing in solidarity with his constituents. However, the number of jailings compares to the millions who refused to pay and is far fewer than would have been the case if there was no organised campaign.

Finally the government announced in March 1991 that they would be scrapping the tax by 1993. We continued to support people who were threatened and campaigned for the writing off of the debts. Many were actually secretly dropped by councils at a later date.

This movement, which united young and old, showed that working-class people can win battles. It also showed the critical role that a party with the right ideas can play in the struggle.

See The Rise of Militant – Militant’s 30 years by Peter Taaffe

Available from Socialist Books.

Anti-war movement 2002-2003

Young people take action

In 2002 and 2003, before the US and UK invasion of Iraq, a mass anti-war movement sprang up across the world. At its height, in February 2003 there was a demonstration of two million people in London, Britain’s biggest ever demonstration. The Socialist Party and the youth group International Socialist Resistance (ISR) played an integral role in this movement.

Tom Baldwin, an ISR activist at the time describes how, by taking action in their millions, young people shattered the myth that they are apathetic and lazy.

Huge anti-war demonstration in London in 2003, photo Paul Mattsson

One of the most important aspects of the movement was the school student strikes. These showed, not just the strength of feeling among young people, but also their willingness and ability to take action. It was the ISR-initiated demand for a walkout on whichever day the war started – referred to as ‘Day X’, that really captured young people’s imagination (Day X turned out to be 20 March 2003, with a rehearsal on 7 March). To build support for it ISR members handed out 60,000 leaflets on the massive 15 February anti-war demonstration.

Students took the leaflets into their schools and colleges and showed them to friends. The demand spread from school to school and town to town and preparations were made. The schools and authorities were beginning to prepare too. They tried to intimidate students, sending letters home to parents, even locking school gates. On some demonstrations police confronted young people with dogs and horses. As a campaigner in Bristol, I received a phone call from the local education authority threatening legal action for ‘encouraging students to truant’.

But as the students showed, these strikes had nothing to do with truancy. They were a democratic protest. Thousands of students up and down the country walked out that day and joined town centre demonstrations, often staying several hours until they were joined by workers. Young people responded to ISR’s call because ISR made it clear that school and college students have a mind of their own and their voice matters.

Appeal to workers

An important part of our approach was calling on the youth to appeal to the workers’ movement. Approaches to staff trade unions in the schools were key to overcoming opposition from the school and college authorities. We campaigned for the next step to be a 24-hour strike of workers.

A call for this from the trade union leaders could have had a huge effect and a strike on this scale would have threatened the interests of the British ruling class and could have forced the government back. Another important aspect of our approach was the need for a political alternative to the big business parties, all of which supported the war in some way.

While the anti-war movement did not ultimately prevent the war on Iraq, it did have a huge effect. It was the first step in the radicalisation of a whole generation of young people, some of whom are now active in Youth Fight for Jobs and the Socialist Party.

See www.socialistparty.org.uk/html_article/2003-293-p7 for reports of school student action internationally.