Urgently prepare a general strike as the next step

Lukas Zöbelein Sozialistische Organisation Solidarität (CWI Germany) and Robert Bechert International Secretariat, CWI

Events are moving rapidly in Iran.

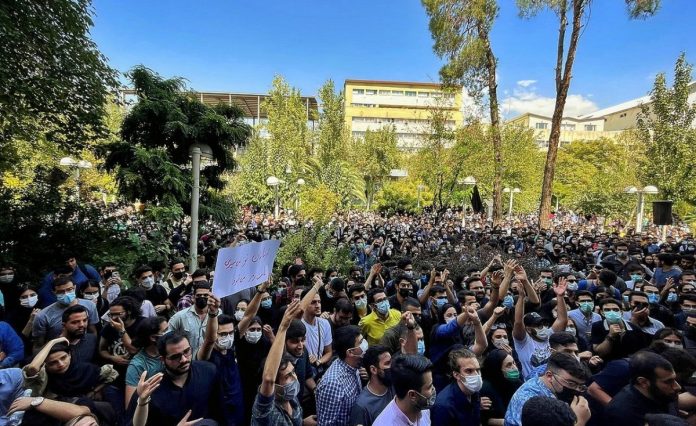

Despite massive repression – with over 200 murdered and thousands of demonstrators, and now strikers, being arrested – increasingly revolutionary protests continue to grip Iran. These have lasted for more than four weeks and have now widened in scope, especially as strikes in support of the protests have begun. All this underlines the new quality of the movement that broke out after Jina Mahsa Amini’s death at the hands of the so-called ‘morality’ police.

Initially the protests were led by young people, especially women and teenagers. The deputy commander of the so-called Islamic ‘Revolutionary’ Guards (in reality the counter-revolutionary guards) has said that the average age of those arrested is 15 years old. Now protest strikes have spread in the oil sector, a key resource as Iran has roughly 10% of the world’s proven oil reserves.

Repeatedly, the streets have echoed to the call: “Death to the dictator”. In response there has often been brutal repression and, in a few areas, exchanges of gunfire between security forces and protesters. But the military and security forces do not exist in isolation; revolutionary movements can affect them. While most have so far stood by the regime, significantly, one video has shown riot police in southern Tehran walking, without their helmets, alongside the demonstrators rather than attacking them.

Despite its Kurdish origin, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (Woman, Life, Freedom) has become a main slogan of the movement as it spreads throughout the whole country. This illustrates how Iran’s ethnic divisions can be overcome on the basis of common struggles. Significantly, the regime has met the protests in areas populated by ethnic or religious minorities, like the Kurds and Baloch, with greater repression. To prevent the regime using divide-and-rule tactics, the movement needs a concrete programme on the national question, which advocates equality and includes the right to self-determination of the oppressed nationalities, while calling for joint struggle against the regime.

The explosive spread of the movement throughout Iran can be traced back to decades of fermenting anger over social injustices, regular repression of opposition, rigging of elections by blocking candidates and, in particular, the regime’s brutal oppression of women.

The regime has also been undermined by economic crisis. Partly under the impact of western sanctions, the economy is between 4% and 8% smaller than it was in 2010. At the same time it is ravaged by inflation. Food prices are up 70% compared with a year ago, in the last 15 years real household consumption has fallen by 29% in cities and almost 50% in rural areas. The government itself estimates that a third of Iran’s nearly 89 million population live in poverty. The economic crisis has particularly hit women, the number of women working has dropped by 20% in four years and the unemployment rate among women graduates is double that of men, when 60% of Iran’s university students are women.

It is against this background that Jina Mahsa Amini’s death sparked off this mighty movement, which has so far been mainly carried forward by teenagers and young adults.

Currently there are regular street battles with police and units of the volunteer Basji militia, who are part of the ‘Revolutionary’ Guards. This shows how deep the rejection of the regime is. Many will have seen some of the videos circulating of schoolgirls removing their hijabs at school and clashing with Basji and police spies loyal to the regime, who monitor religious rules in schools. The Coordinating Council of Iranian Teachers’ Unions has called on students to turn classrooms into spaces for democratic discussion and to expel all forces loyal to the regime from classrooms. This Coordinating Council statement was issued the day before its third day of strike action during the ongoing movement.

The strikes in Kurdish areas, of teachers nationally and of sections of petrochemical workers are important. These can be the spark to wider action that could show the strength of the movement and the weakness of the regime’s base. Some actions are developing through local initiatives. That is very positive but it is increasingly urgent for the protests to go to a higher level. The regime will not be brought down just by riots and demonstrations – which it hopes to sit out. A combination of a 24 or 48-hour general strike with mass demonstrations would be an extremely important next step in giving a shape to the movement. The formation of local bodies of representatives of workplaces, communities and educational institutes to organise such a strike would be an important step towards organising the movement and beginning to establish an alternative power to the regime’s structures.

Since 2017-18, there has been a general rise in workers’ struggles and the growth of semi-legal independent workers’ organisations in some workplaces. On May Day, 2021, a joint statement was issued by 15 Iranian working-class organisations which listed a series of demands and also called for the creation of “a coalition council among all the workers, teachers, employees, retirees, women, students, and the unemployed… This is not just a demand among others, but the urgent platform for aiming at a new organisation of work in our society”. This statement ended with the declaration that “the emancipation of the workers is brought only by the workers’ themselves!”

Now the militant Haft Tappeh sugarcane refinery workers have issued an appeal for a “nationwide strike”. This call needs to be urgently taken up. Likewise the idea of a “coalition council” mentioned in the joint May Day statement needs to become a reality. This may require, as the next step, coordinated strikes from all semi-legal trade unions that can set an example and be rapidly further developed into a 24 or 48-hour general strike.

A campaign that prepares for a general strike is more necessary than ever. This needs to include a programme that links the immediate issues with the need for regime and system change. Immediate issues like the release of all detained protestors – trade union and worker activists, and political prisoners are starting points. So too the freedom of women to wear the clothing of their choice and to work where they want, and the abolishment of the ‘morality’ police, the so-called ‘Guidance Patrols’.

But these demands are just the beginning. The right to freely organise, in the workplace and politically, as well as the abolition of all oppressive structures, laws, and organisations (like the Basji), are essential. Economic demands such as the reduction of the working week and an inflation-proof minimum wage are immediately important.

The teachers’ Coordinating Council call for classrooms to become spaces for discussion can also help stimulate the necessary debate on the question of what comes after the current regime, something that also needs to develop in workplaces and communities. Schools could become one of the venues in which such wider bodies could meet. Discussions in which the questions of how to secure democratic rights, what sort of society should be created, and whether Iran should remain capitalist or carry through a socialist break can be debated. But alongside discussions on programme, these bodies can begin to coordinate the struggle, including organising the defence of protesters and strikers from attack.

Splits in the elite

Ex-president Kathami has called on the repressive organs to take the side of the protesters, and it appears that parts of the military have already referred positively to his statement.

Likewise, the now detained former prime minister Mir-Hossein Mousavi sent out a message urging the security forces to end the repression, saying: “Armed forces! The powers vested in you are for defence of the people, not their repression; for protection of the oppressed, not service to the powerful and mighty. The hope is that you will stand on the side of truth and the nation. Your duty is secure the peace for the millions and especially the downtrodden, and not to consolidate the power of oblivious officials.”

These are examples of divisions widening within the elite. While significant, it also needs to be kept in mind that members of the so-called reformist wing of the regime, like Kathami and Mousavi, are essentially concerned with saving the Islamic Republic’s basis. To do so they may, for example, abolish the ‘morality’ police and the strict clothing regulations for women, but otherwise leave much of the regime intact. Even if elements like this want to remove large parts of the Islamic Republic’s structures, it is clear that they would want to build a more ‘normal’ capitalist state, something which would leave the economic and social demands of working people and youth unanswered.

But the more conservative elements in the ruling class have not given up, they try both to divide and crush the movement. The speaker of the parliament, a former ‘Revolutionary’ Guard commander, has urged protesters not to allow the demonstrations to become “destabilising” while promising to “amend the structures” of the country’s morality police.

Faced with the growing strength of the protests, President Raisi tried to appease the movement. On 15 October, the official Irna news agency circulated a statement by Raisi saying that the regime would “review, revise, update” some of the laws in force in the country. He added that a social dialogue is needed to dispel “doubts” within society and that “we should also see if we have achieved the goals set and if not, where the problems lie.”

The regime is undermined by its own divisions, and faces possible overthrow. But that immediately poses the question of what next?

The current movement has a cross-class makeup, it encompasses different elements opposing the current rulers. However, once the regime is overthrown or even severely weakened, the question will be posed: who takes over the power?

Inevitability in every revolution this question is posed. There can be powerful calls for unity, or at least unity against the forces of the old regime, which are made in arguments for the formation of a ‘temporary’, ‘provisional’, ‘unity’ government to ‘secure’ the revolution, organise elections etc. Certainly there can be unity of action against counter-revolution, but that is very different from the question of workers’ organisations collaborating with pro-capitalist forces in a government maintaining the capitalist system.

The workers’ movement needs to set its own agenda, a socialist agenda which combines together the immediate demands with the need to break with capitalism, so that the working class can begin the socialist reconstruction of society. Today the revolution needs to seize the opportunity to do this and not limit itself to ending the decades-long repression by the counter-revolution that pushed the working masses aside and seized power after the mass revolt that ended the shah’s dictatorial rule.

Within the current opposition, liberal capitalists opposing the current leadership or even the entire regime, will want a more ‘normal’ capitalist system without the constraints of the top religious leaders and apparatchiks of the Islamic state bureaucracies. But the continuation of capitalism means that the fundamental issues facing Iran will not be answered, meaning that inevitably class struggles will break out as interests of the capitalists and the working class come into conflict. If the capitalist power is not broken this would pose the danger of counter-revolution, probably not on the same lines as 1979-80, but possibly like in Egypt in 2013.

It is also necessary for the Iranian working class and youth to have no illusions in the role of western imperialism. Aware of the potential strength of the Iranian working class they have long attempted to cultivate links with Iranian oppositionists and workers’ leaders with a view to drawing them into a pro-capitalist orbit.

The alternative that the workers’ movement needs to stand for is the replacement of the present regime by a provisional government made up of representatives of the working class, youth and poor which immediately takes action to implement the revolution’s basic demands. At the same time, it needs to encourage the development of local democratic bodies which can become the foundation of a new regime. Such bodies could be the basis for the election of a revolutionary constituent assembly to decide the country’s future.

But to achieve this there needs to be a socialist force, a revolutionary party, which can argue for these ideas. This was the case in Russia in 1917 when Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, refused to join the pro-capitalist provisional government and instead campaigned to win majority support among the working class for socialist revolution. That is the example which needs to be followed.

The unfolding new Iranian revolution is a tremendous development; it is already starting to inspire youth and workers in other countries. If successful, it will have an electrifying effect in the Middle East and beyond. The energy and bravery of the young people are an example to all. What is needed now is the widening of the movement and a clarification of the concrete steps necessary to both defeat repression and to open the way to real liberation from oppression and all the ills of capitalism.