For a 48-hour general strike, as the next step towards overthrowing the regime

Lukas Zöbelein, Sozialistische Organisation Solidarität (CWI Germany)

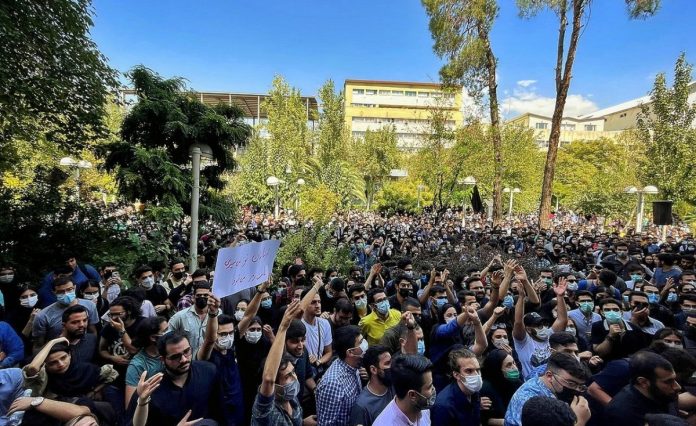

The 40-day mourning period after Jina (Mahsa) Amini’s death ended with protests taking place in 30 Iranian cities. The largest was in Saqez, her hometown in the Kurdish part of Iran, attended by people from all over Iran and especially from Kurdistan. About 100,000 people took part and, despite the security forces attempting to seal off the entire city, many were able to make their way to her grave.

Three days later the commander of the so-called Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, Hossein Salami, issued a threat that “demonstrators should not overstretch the patience of the system. Today is the last day of the riots.” It was significant that he also vaguely mentioned making some concessions, reflecting the strength of the opposition.

So far, however, the regime has not been able to stop the protests despite the continuing brutality of its repression. The very next day there were more large protests, especially in the Iranian part of Kurdistan, and at almost all of the country’s universities.

Even before, revolutionary youth had founded councils in Sanandaj, the capital of the province of Kurdistan, and also in other cities. So far, the largest are said to be in Sanandaj and in Tehran. This is an important development in itself, and a significant step forward.

Recent appeals issued by both a few of the semi-legal independent workers’ organisations and some of the youth councils are attempts to propose the next steps for the developing movement. This is crucial as the regime is trying to use a mixture of repression on the streets and in the courts to hold back the movement, while hoping that the protests will exhaust themselves. Only a strategy based upon organising the movement, adopting a revolutionary programme and stepping up the struggle can defeat the regime’s strategy.

The Women and Youth Committee of Sanandaj Neighbourhoods’ initial appeal called for the formation of popular councils throughout the country:

“Now is the time to turn our networks of communication and our links, which are the achievements of our struggles in this period, into a more evolved organisation. Now is the time to think about creating neighbourhood committees and councils, and student councils in universities and in schools. Our call to other parts of the society is to form workplace and neighbourhood committees and councils. Whether these forms of organisation are clandestine or open is up to the balance of power, which can be determined by revolutionary youth and freedom-loving people locally.”

If this appeal is seriously followed up, not just by the youth, but by the working class and poor, it could be a decisive development. In particular the establishment of such structures in factories and workplaces is central, since they can be key to the preparation and execution of the working class both fighting for its own demands and also spearheading the movement for democratic rights, against the repressive regime and the capitalist system which is incapable of taking society forward.

Such organisations could be decisive in organising mass protests, synchronised actions and a general strike which, as with the 1978-79 revolution, could topple the regime.

No illusions

It is significant that the Sanandaj committee has no rosy illusions about the regime, something which is understandable given its long history of repression, which has been added to recently, with over 300 killed on the streets and thousands arrested. In another statement they wrote:

“The creation of these councils will help the scattered struggles of the youth to become more coordinated, to develop a programme, to develop plans and to choose certain tactics. These immediate and effective measures, in addition to providing the youth movement with order, direction and planning, will also prevent individual mistakes, and will also increase the confidence of those fighting on the streets and prevent wasted efforts.

“In addition, taking a lead in this manner, increasing the level of organisation and developing a distinct leadership, will increase the confidence of different social strata in the youth and provide the basis and possibility for them to join the movement. We insist that all young people unite and coordinate in a single movement, with a single organisation, leadership and plan in neighbourhoods, universities and high schools, and form a single front.”

All this shows that the ‘Women and Youth Committee’ in Sanandaj aims to unite the revolutionary youth movement in a nationwide organisation and to give it a united programme. In a similar development, the Isfahan and Tabriz Student Coalition listed a number of demands that clearly flow from their own experience and the events that have taken place:

- Protest the killing in Sistan-Baluchistan

- Protest the bloody massacre of Evin

- Protest the brutal attack on the children of Shahid Ardabil School, the killing and wounding of female student prisoners, and other arrests of children;

- Protest the militarisation of the cities in Kurdistan

- Protest the repeated arrests of political activists, teachers, youth and even schoolchildren

- Protest threats, warnings, arrests and attacks on university students

Such demands can have a mobilising effect at the moment, especially on the youth of Iran. But in order to be able to mobilise all parts of the working class, a wider programme is needed that unites economic, social and democratic demands, and consciously appeals to workers and others across Iran.

Sanandaj itself is the second largest Kurdish city in Iran and capital of the Kurdish province, but it is only the twenty-third largest city in Iran. The regime would love to play the nationality card of ‘divide and rule’, trying to isolate the militant opposition in ethnic and religious minority areas like those of the Kurds, Balochs and Arabs.

A conscious approach is needed to prevent this happening. Consistently clear demands against the repression across the whole of Iran, clear calls for democratic rights, the demand for a minimum wage on which one can live, action against unemployment, as well as the democratic control and management of the economy by the workers and the population itself need to be put forward. These should also include a reduction of the working week to 30 hours, so that the work can also be distributed to those who currently have no work.

Democratic demands

The democratic demands must include full equal rights for women, including the right for women to wear what they want, to be allowed to choose where they work and travel. This is a key question as this revolutionary youth movement was sparked off precisely against the repression of women, and women, especially young women, are heavily involved in the struggle.

The call for fully democratic elections at all levels of society is central alongside the call for a revolutionary assembly which can decide the future character of Iran, unlike in 1979, when the Khomeini clique only allowed a formal ‘yes/no’ vote on the new constitution they themselves had written.

The women and youth bodies that have already sprung up correctly recognise that to organise and defend the movement the development of councils rooted amongst the active layers, workplaces and communities can be a key step. The widespread formation of such bodies would be a direct challenge to the undemocratic and bureaucratised structures of the regime. Through the activity of such councils, a leadership can also emerge organically to represent them at local, provincial and national level. Particular attention needs to be paid to ensuring that any leadership represents and is accountable to its base, while also including women and people from the ethnically, religiously, and culturally oppressed sections of the population.

It is clear that since these youth bodies developed in October, the protests are continuing. The first weekend in November saw demonstrations in many cities from Tehran to the central city of Yazd and the northern city of Rasht. Students in a dozen universities, including in the northern cities of Rasht and Amol, held protests on Sunday chanting “Death to dictators”, while in southern Tehran demonstrators chanted “Clerics get lost”.

In the Kurdish city of Marivan, it was reported that security forces fired on crowds who had gathered after the funeral of another female protestor, Nasrin Ghaderi, who was killed while demonstrating in Tehran.

However, in all spontaneous movements there is a danger that they get stuck at one level and, over time, lose momentum, which can result in the movement beginning to decline. To prevent this happening, concrete steps need to be proposed and built for. The Isfahan and Tabriz Student Coalition’s list of demands ended with this call: “We must respond to the limitless crimes of the oppressors in forms of a general strike, school closures, teachers’ protest rallies, street and neighbourhood rallies and protests.”

This is a vital demand, and the youth councils could have an important role by arguing for a nationwide general strike, possibly of 48 hours, as the next step. Such a strike, if successful, would demonstrate in practice that the opposition is strong enough to stop the nation and, by exposing the weakness of the regime, putting the question on the table that this means that the opposition is strong enough to run the country.

The recent Sanandaj youth council statement shows an understanding of this when it says:

“Today, in addition to the unwavering support of militant teachers of the National Coordination Council, we are witnessing labour strikes in the south and in the key sectors of oil and petrochemicals, Haft Tappeh workers, fuel lorry drivers, etc. We hope that other sections of the working class and workers in the transport and urban services sector will join the nationwide revolutionary movement. Undoubtedly, the joining of different parts of the labour movement to this revolutionary uprising contains the promise of advance and victory.”

To be able to help to go to the next stage, the revolutionary youth councils need to concretely turn to the working class and poor to advocate action and create bodies to organise activity where none currently exist.

These developments are an important and extremely significant step. They can also be the basis of organising the defence of the movement from the continuing attacks of the regime’s security forces, while making efforts to split them by appealing to their ranks to side with the movement. The organisation of the movement both takes it forward and provides an opportunity to discuss not only the next steps but what should be the struggle’s goals.

As in 1978-79, the working class is the key force that can change society. To build support for a 48-hour general strike requires an organised mass campaign that involves the semi-legal unions and workers’ organisations. Some of these have been actively fighting against the brutal rule of Iran’s religious and political leaders for more than a decade, and have thus accumulated experience of methods of struggle and strategies that could positively influence the revolutionary youth movement.

At the same time, the councils and the movement must also have a discussion about what can come after the theocratic regime. The CWI argues for a government led by the workers, poor and youth that begins the construction of a democratic socialist Iran.

Socialism

The CWI has consistently argued that: “The workers’ movement needs to set its own agenda, a socialist agenda which combined together the immediate demands with the need to break with capitalism so that the working class and power can begin the socialist reconstruction of society. Today, the revolution needs to seize the opportunity to do this and not limit itself to only ending the decades-long repression by the counter-revolution that pushed the working masses aside and seized power after the mass revolt that ended the Shah’s dictatorial rule.

“The continuation of capitalism means that the fundamental issues facing Iran will not be answered. Inevitably, class struggles will break out, as the interests of the capitalists and the working class come into conflict. If the capitalist power is not broken this would pose the danger of counterrevolution, probably not on the same lines as 1979-80, but possibly like in Egypt in 2013, as the ruling class moves to secure its position.”

This means that the workers’ movement, the poor and the revolutionary youth must stand for the replacement of the present regime by a provisional government made up of representatives of the working class, youth and poor, which immediately takes action to implement the revolution’s basic demands and begins the socialist transformation of Iran, something which would have an international echo not just in the Middle East but worldwide.