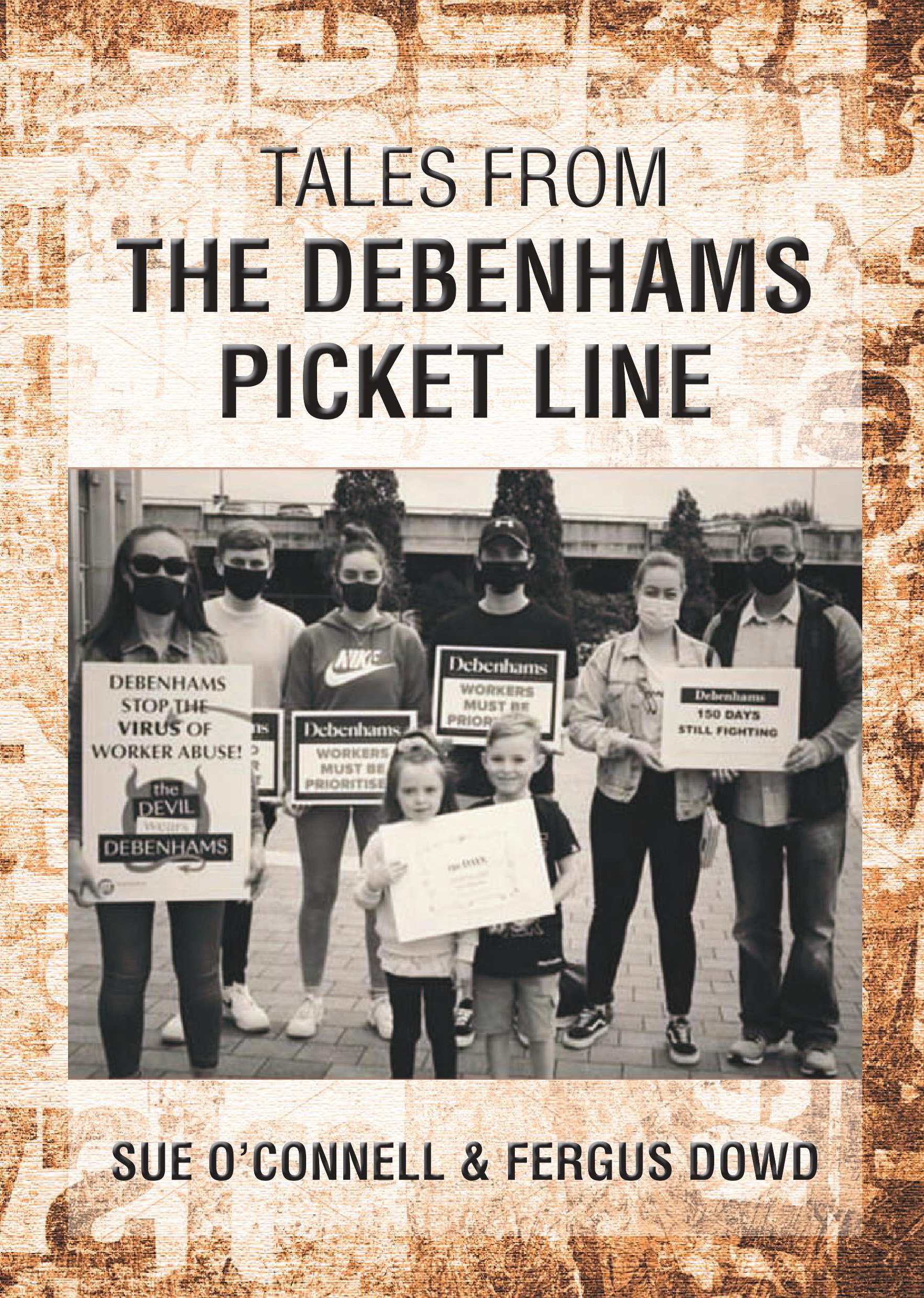

Non-fiction: Tales from the Debenhams picket line

Iain Dalton, Leeds Socialist Party

Less than one month into the Covid-19 lockdown in Ireland, retail workers at Debenhams received the stunning news that their jobs were no more, and the company was pulling out of physical retail in Ireland. This was all the more shocking for the workers because they had received an email saying that while the UK parent company had gone into administration, all was fine in Ireland.

The focus of the book is the run-up to that announcement on 9 April 2020, and the struggle for over a year afterwards of Debenhams workers across Ireland. These workers initially fought to keep their jobs, but when this failed, they fought for the previously agreed redundancy payments, which the company announced it would not pay. The company instead directed Debenhams workers on how to apply for statutory redundancy via the government, a tactic that was subsequently applied to the Debenhams UK workforce.

In several ways, Debenhams was typical of the retail sector, particularly department stores. Many of these companies have been repeatedly taken over, loaded with debt, and had the stores sold and leased back. For example, Debenhams itself was bought in 2003 by a consortium known as Baroness Retail Limited, which invested £600 million, but also loaded the company with £1 billion of debt. Not only did it sell off the buildings of 23 stores in 2005, raising £495 million, but was able to collect £1.2 billion when the company was refloated on the stock market within three years!

Debenhams had come to the south of Ireland in 1996, then took over the Roche department stores where Mandate, the main union covering retail workers in Ireland, was a recognised trade union. This meant, unlike in the parent company in the UK, Debenhams workers in Ireland had a collective trade union agreement.

Pivotal to this struggle was the way the workers themselves organised, and in particular their elected shop stewards. As the book describes, the shop stewards responded by creating a WhatsApp group to coordinate among themselves, and contacted their TDs (MPs), with active assistance provided by a number of left TDs.

Union leadership

While Mandate’s national leadership had made the dispute official, with a 97% mandate for strike action from the Debenhams membership, the reality was the union’s leadership sought to lower the sights of what the workforce should settle for at all stages of the dispute. This lack of confidence in the preparedness of workers to struggle, and therefore adopt tactics of concession bargaining, will be familiar to members of the UK retail union Usdaw.

A rebuttal to this mood was the resourcefulness of the Debenhams workers themselves. Whether it was organising picket lines across the 11 stores, speaking to the media, organising rallies with support from other trade union and left activists, or even occupations of three of the stores, the Debenhams workers proved themselves more than capable.

12-hour and then 24-hour picketing became necessary as the dispute went on, and pickets realised their main leverage over KPMG – the liquidators appointed by Debenhams – was the stock still held in the stores, valued at around €23 million. On many occasions the workers successfully turned back vehicles which had come to take the stock away.

While the book showcases much of the solidarity received by the workers from various sources, an omission is discussing the action taken by Debenhams workers in Manchester. Inspired by workers in Ireland, they held protests outside their store every Saturday for several weeks.

While some in Usdaw rallied in support of these workers and those in Ireland, including this author, Usdaw’s then president Amy Murphy, and several members of the union’s executive council, the response of the union was even more lacklustre than that of Mandate. Using the low union membership in what was an unrecognised company as an excuse, they failed to mobilise the union behind the members it did have who were taking action!

Spreading the action in Ireland to the UK would have massively increased the pressure on Debenhams management to address the redundancy issues facing workers.

Ultimately the strike was beaten by a combination of two factors. Firstly, the repression of the state wielded on the side of Debenhams and KPMG. The Gardai (Irish police) tried to move pickets on using emergency Covid legislation, and then removed pickets under a court-imposed injunction. The Gardai was also used to remove workers from the two store occupations that took place in Dublin and Cork.

But even this stacked power of the state machine, brought to bear on the side of the employers and their liquidators, could have been defeated. What was missing was leadership from Mandate mobilising its membership and the broader trade union movement in support of the workers. Despite calls for action, the ICTU, the trade union federation in Ireland, never mobilised the wider trade union movement either.

Despite this, significant rank-and-file activists did support the Debenhams workers, including Karen Gearon, a leader of the 1984-87 Dunnes Stores anti-apartheid strike. If larger numbers had been mobilised, it could have posed the possibility of mass pickets able to make the injunctions won by KPMG unenforceable.

Instead, a majority of Debenhams workers who could see no way forward after rejecting previous poor settlement offers, felt forced to accept ‘training scheme’ funding which was a poor substitute for the redundancy rights they should have had.

The tremendous courage of the Debenhams workers is a lesson to all workers, and shines through in the book. This struggle is one that should inspire any workers facing the closure of their company and workplace, and deserves to be learnt from, so that next time such a situation faces retail workers they can win a substantial victory.

- Tales from the Debenhams picket line by Sue O’Connell and Fergus Dowd is available at debspickettales.ie