Niall Mulholland, East London Socialist Party

Visitors to museums and educational establishments, such as the V&A Museum in London and Oxford University, will be acquainted with the name of Sackler. This is the billionaire family from the US which, for decades, has funded many aspects of these institutions, and other world-renowned galleries and universities, like the Louvre, Yale, and Harvard. Less well known until revelations in recent years is that the Sackler’s great wealth comes from the suffering of many people, particularly the poor.

An estimated half a million Americans have died from opioid-related overdoses since 1999, and millions more have become addicted. The Sackler family, through their company Purdue Pharma, made a painkiller in the 1990s called OxyContin, which is twice as powerful as morphine. They sold it as a slow release drug and claimed that it was less addictive than other opiates.

Scandalously, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved OxyContin without testing the company’s claims. This created the conditions for an opioid epidemic in the United States and elsewhere. Not only was the drug addictive for many users, addicts soon discovered that by crushing the OxyContin pills they could ingest it much faster and get an immediate high.

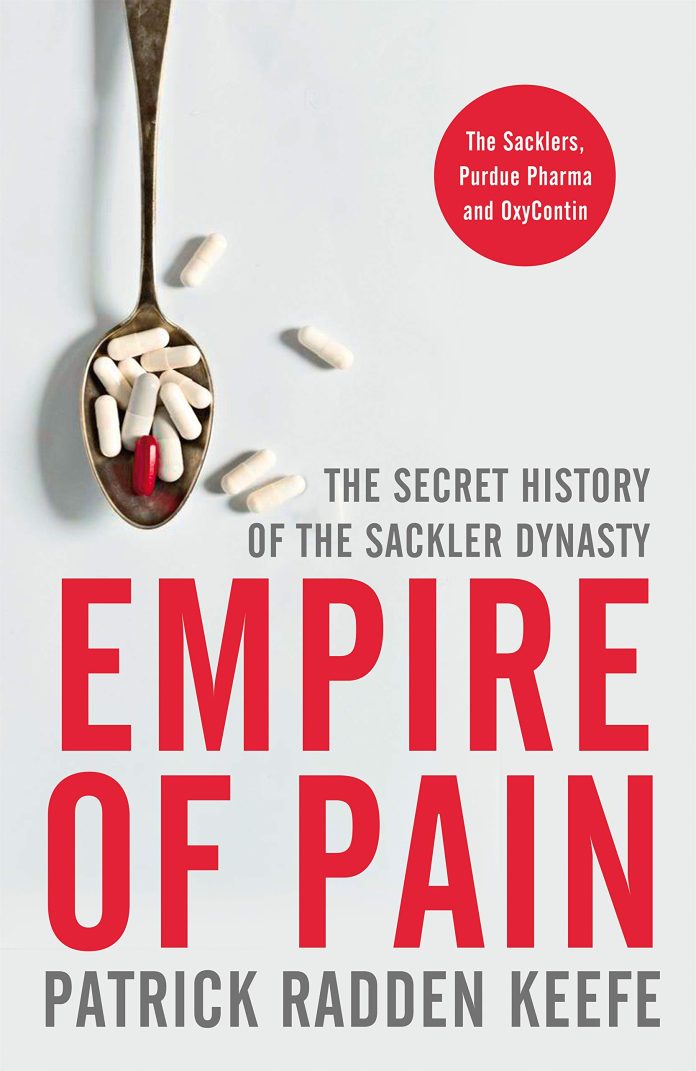

All of this is brilliantly described in Patrick Radden Keefe’s book, ‘Empire of Pain’. Keefe’s last book, the acclaimed ‘Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland’, is also well told. It centred around the disappearance of Jean McConville in 1972, a widowed mother of ten abducted from a home in Belfast by the IRA and never seen alive again, and the Price sisters who were at one time world-famous Irish republican prisoners in an English jail.

In Empire of Pain, Keefe traces the history of the Sackler dynasty beginning with Arthur Sackler, the eldest of three boys born to a Ukrainian Jewish grocer in Brooklyn in 1913. Arthur funded himself through college and medical school, partly by working in advertising and, with his two younger brothers Mortimer and Raymond, established or bought a number of businesses, including one which would change its name to Purdue Pharma.

Arthur used his advertising experience to aggressively market his pharmaceutical products, including Valium, with often misleading and false information. Valium sold widely in the 1960s and 1970s, and made the Sackler’s rich.

Arthur liked to work behind the scenes concerning his company but he was a keen collector of Asian art and a high-profile philanthropist. He drove hard to get the Sackler name on the walls of art galleries, universities and museums throughout the world. This granted the family name a veneer of respectability that belied the sordid origins of its enormous wealth.

Richard Sackler, the son of Raymond, became de facto head of the family business after Arthur’s death in 1987. Once the company had devised OxyContin, it followed Arthur’s policy and mounted an aggressive and false publicity campaign, employing an army of sales people to lobby medical practitioners hard to sell OxyContin, and including enticing them with material inducements. The plan was a great success. It is estimated that since OxyContin went on sale, the Sackler family profited by $14 billion, which was often put into offshore shell companies and bank accounts.

Keefe describes the heroic efforts of a journalist, Barry Meir, from the New York Times, to expose the Sackler’s role in the opioid epidemic. However, with their huge wealth and influence, the Sacklers were able to lobby the Times, which subsequently took Meir off the subject.