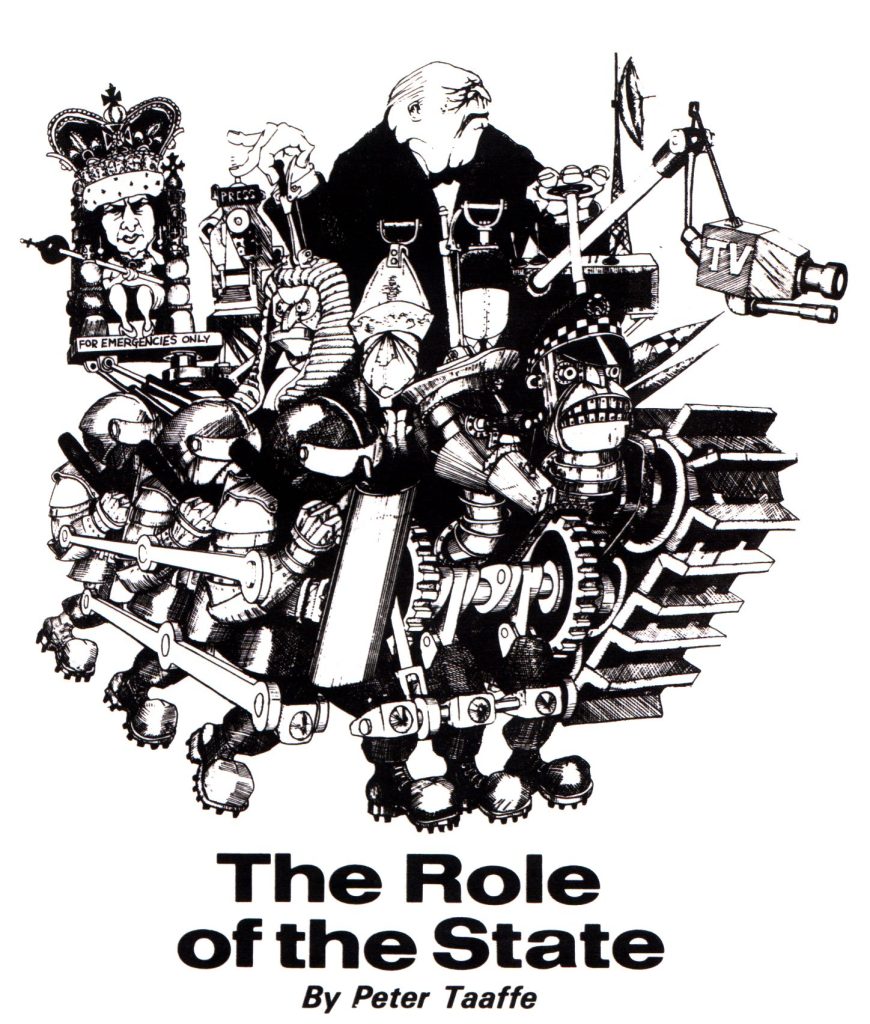

The first of three articles by Peter Taaffe on the state in the Militant Newspaper: —518 (5 September 1980), 523 (10 October 1980), and 524 (17 October 1980)

An Apparatus of Coercion

One of the major issues which divides Marxism from reformism within the labour movement is that of the state. In the last analysis—as Marx, Engels and Lenin pointed out—the state consists of armed bodies of men and their material appendages, i.e. prisons, etc. Lenin wrote that “it is impossible to compel the greater part of society to work systematically for the other part of society without a permanent apparatus of coercion.”

But does this apply to the modern “democratic” state? “No”, say the capitalist professors. They maintain that the teachings of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky are a little “old-fashioned”. And the theoreticians of the so-called “Communist” Party are at one with this conclusion. After all, we have universal suffrage (the right to vote) and democratic rights in Britain. How then is it possible to talk of the modern state in Britain, America, etc. being a machine for the domination of one class by another?

And yet an examination of the state in Britain today will show that it is firmly under the control of the capitalist class. All the key positions in the civil service, the police, and particularly the army are in the hands of people who have been specially selected by education, outlook, and conditions of life loyalty to serve the capitalists.

This is particularly the case with the summits of the army. Trotsky once described the officer caste in a capitalist army as “the guard of capital…the selection of the individuals, their education and training makes the officers as a distinctive group uncompromising enemies of socialism. Isolated exceptions change nothing.” The social composition of the officer corps in Britain completely bears out Trotsky’s statement. In the early 1960s it was estimated that nearly 50 per cent of the intake of the officer corps came from the existing officer class, nearly half came from public schools and nearly 77 per cent came from the “AB” socio-economic group, that is the “top 12 per cent” in society.

Since then there has been a widening of the intake into the officer corps, but the majority of the officers still come from the ‘elite’ of society. Even the small number of officers from the middle class and working class absorb the outlook and class attitude of the officer class as a whole. It could not be otherwise given the rigid hierarchical structure of the army. Indeed, the army expresses in a sharper form the class division within society as a whole. The pro-business and anti-working class outlook of the officers is reinforced, moreover, by the interpenetration of the tops of the army with big business. In the period of 1971-76, for instance, 97 serving officers and 86 defence ministry civil servants joined firms which had contracts to supply arms to the ministry of defence. This same officer class, together with the ruling class as a whole, at the same time stubbornly resists all attempts to give greater democratic rights to the ordinary “squaddie” in the British army.

A similar picture emerges if we examine the judiciary. The judges are one of the most conservative bulwarks of the system. As one commentator put it, “they are men advanced in life. They are for the most part men of conservative disposition.”

The monopolies have more and more fused with the state machine in the post-war period. This is perhaps shown most vividly in the movement between the tops of the civil service and the boardrooms of the monopolies. A game of musical chairs takes place between the civil service chiefs and the directors of the monopolies. A most blatant example was the career of the late Lord Armstrong, who moved from chief advisor to the Heath government—he was openly referred to as “Deputy Prime Minister”—to Chairman of the Midland Bank. Mr John Lippet, who was involved in various export activities as a civil servant in helping GEC and other companies to win power station contracts abroad, also recently left the civil service to join the boardroom of GEC!

These few facts alone are sufficient to completely shatter the image of the impartiality of the state in Britain. It is a vehicle for maintaining and defending the dominant interests of the capitalists. This has been demonstrated again and again in the experiences of Labour governments with the civil service and with the chiefs of nationalised industries. Labour ministers have complained—unfortunately only when they have left office—of the obstacles placed in their path by the topmost civil servants.

Reflecting in the Sunday Times (10 June 1973) on her experiences with civil servants as Transport minister in the 1964-70 Labour government, Barbara Castle wrote: “I have no doubt that the civil service is a state within a state…how effectively the civil servants impeded us by saying we could not do some of the things our successors are now doing with remarkable facility…It took several months even to mouth the words ‘integrated transport policy’.” Barbara Castle gives a glimpse of how Labour ministers can become puppets of the civil service who “control every single ten minutes of a minister’s day and night—ministers can’t even choose who drafts their replies to letters.” Their political bias is shown by the comments of one top civil servant to Barbara Castle: “Well I must admit, minister, it is true that we do tend naturally to have more contact and therefore more affinity with the employers’ organisations. It’s not that we wouldn’t like to have contact with the trade unions. But we just don’t know how to set about it.”

Sometimes the opposition of civil servants borders on outright sabotage. Thus Brian Sedgemore, in his recent book The Secret Constitution (1980), points out that when Tony Benn was Minister of Energy during a strike at Windscale, his civil servants informed him that unless troops were used to move nitrogen across a picket line a “critical nuclear explosion would take place”. Sedgemore diplomatically comments that these warnings were “unfounded”. The Civil Contingencies Unit at the Cabinet Office had prepared a plan “to break the strike with troops, thus leaving Tony Benn as a sort of latter-day Churchill” {The Times, 29 May 1980).

If the civil servants are prepared to undermine the measures of right-wing Labour governments, imagine the lengths to which they would be prepared to go to frustrate and sabotage the attempts of a left Labour government! Is not the lesson for the labour movement that it is impossible to use the present civil service, army and police tops to carry through the socialist transformation of society as envisaged in Clause IV, part 4, of the Labour Party’s constitution? Won’t these same forces actively sabotage such attempts of the labour movement to change society?

From a long-term point of view, the untrammelled development of the state in Britain poses enormous dangers for the working class. The lessons of Chile, written in the blood of more than 50,000 martyred workers, is a warning to the labour movement here. It was no accident that a precondition for allowing the Allende government to power in Chile in 1970 was his agreement with the capitalist parties preventing the setting up of “private militias” or the appointment of military officers not educated at technical military academies. This effectively forbade any “interference” with the training of the officer caste, the running of the military academies, or the organisation by the Popular Unity government of a workers’ militia to defend itself and the gains of the workers against counter-revolution. In the turbulent period which is opening up, the strategists of capital clearly do not rule out the possibility of developments in Britain along the lines of Chile. The ending of the long economic upswing and the beginning of the era of economic instability, with short booms and deeper slumps, has brought in its wake a period of social and economic upheaval. The capitalists have been forced—particularly in Britain—to abandon the methods of the last thirty years and to go over to the offensive against the working class. They have also been forced to consider the possible use in the future of the same brutal methods as in the past—i.e. the police and army—to curb the movement of the working class.

This is shown, on the one side, by the big wage increases to the police and army granted by Thatcher. On the other side, is the fact that in this year alone more than 500 workers have been arrested on the picket line. The use of the Special Patrol Group in industrial disputes, and even the use of the army as in the case of the firemen’s strike two years ago, has brought into question all the cherished myths in relation to the state. This is reinforced by the use of the SAS in Ireland and Britain and the widespread use of snooping and telephone tapping by the secret service. This is undoubtedly in preparation for future social conflicts in Britain.

Further evidence is found in the writings of Brigadier Kit-son, in which he advises the army to base its strategy, not on the assumption of a war with Russia, but on so-called “internal subversion”. This is a euphemism for civil war against the labour movement. Added to this are the recently leaked details of the suggestion of the Tory government to organise a scab army of “volunteers” in preparation for the possible conflicts in the winter.

How can the labour movement counter these preparations of the ruling class? An attempt was made under the last Labour government to undermine the reactionary influence of civil servants by placing “advisors” sympathetic to the labour movement in the civil service machine. This very mild measure was denounced by the capitalist media as an attempt to install “commissars” alongside loyal “apolitical” civil servants.

The Transport and General Workers Union, other unions and some Labour MPs, moreover, attempted to persuade the last Labour government to give rank-and-file soldiers the right to join trade unions. This was also denounced as an at- tempt at “political” interference in the armed forces. To their shame, right-wing defence ministers such as Roy Mason bowed to the pressure of the generals and the press, and refused the elementary and democratic right for soldiers to join trade unions.

However, even if trade union rights were granted, would this be sufficient to counter the danger from the state to the labour movement? The army cannot be used arbitrarily against the labour movement and the working class. Splits and divisions within society are mirrored, in however a distorted form, within the army itself, even in a purely volunteer army. Any attempt to use the army against the labour movement anywhere in Western Europe at this stage would be fraught with enormous dangers for the ruling class. In France and Italy the army is largely composed of conscripts. An attempt to use the army against the working class, as in a situation similar to the May 1968 events in France, would result in a complete split along class lines. In Italy, the attempts at various coups over the last ten years, had they come to fruition, would have met with the overwhelming opposition of the conscript rank and file.

However, the leaders of the Communist Parties in France, Italy and Spain, in their approach to the army, play right into the hands of the ruling class. They almost conspire with the officer class to systematically seal off the young workers once they enter the barracks. The Communist Party in Italy “rejects the idea of a soldiers’ trade union as being neither appropriate today or compatible with the specific and peculiar requirements of discipline.” And yet in other European countries the Communist Parties have either supported the existing organisation of soldiers into trade unions or have inscribed such .a demand on their banner.

In Holland for instance, there is a mass organisation for conscript soldiers with about 30,000 members which has been recognised to an extent by the military authorities. There is even a left-wing soldiers’ organisation. In West Germany, where there is a half-conscript and half-professional army, there is also an organisation for conscripted soldiers of about 100,000 members. There is also a trade union for professional soldiers—which includes those working in “intelligence”!— linked to the German TUC (DGB). In Sweden, there is a similar organisation for rank-and-file soldiers and even a “soldiers’ parliament”. The slavish worshipping of the capitalist state by the Italian Communist Party leaders leads them to oppose “the setting up of ‘party organisations’ within the barracks.” Such an attitude is calculated to separate the ranks of the Italian army from the rest of the labour movement. This goes hand-in-hand with demands like those of the Spanish CP, for “modem weapons” to be supplied to the military brass. This attitude could result in disaster for the working class of Italy at a later stage if it remains unchallenged by the rank and file of the Communist Party.

There is no reason at all why soldiers should not enjoy all the democratic rights which ordinary workers in Britain possess: the right to strike, to support political parties of their choice, and to read newspapers, books and magazines of a socialist and Marxist character. Their officer class is not denied the right to choose. In an overwhelming majority, they support the existing system and the parties which defend that system. In Britain, the labour movement must campaign now for the democratic right of soldiers to belong to the trade unions. From a long term point of view, it is also necessary to take the present system of training officers— with the reactionary poison against the labour movement which is instilled into recruits—out of the hands of the specialised military academies and the generals, and put it under the democratic control of the labour movement and the working people as a whole.

In the civil service, too, there must be steps taken to democratise at all levels and to involve working people. This is particularly true in the organisation and management of the nationalised industries. Militant demands that the boards of the nationalised industries be composed of one third from the unions in the industry, one third from the TUC representing the working class as a whole, and one third from the government.

Similar demands, taking into account the concrete situation and differences in each field, have been put forward for the civil service and local government.

However, it would be fatal to pretend, as the Communist Party leaders and the reformist Left of the Labour Party do, that “the democratisation of the state” will be sufficient in itself to guarantee the British working class and a Labour government against the fate which befell their Chilean brothers and sisters. Piecemeal measures will neither satisfy the working class nor the middle class, but will inflame the opposition of the capitalists—and, moreover, give them the time and opportunity to strike a decisive blow against the labour movement. This would above all be the case when attempts are made to “democratise” their state. The capitalists would take this as a signal—particularly if the army is touched—to prepare to crush the labour movement.

Does this then mean that the state must remain untouched by the labour movement, as the right-wing of the Labour Party maintain! On the contrary, measures to make the state more accountable to the labour movement must be stepped up. But the limits of such measures must also be understood by the labour movement. The capitalists will never permit their state to be “gradually” taken away from them. Experience has shown that only a decisive change in society can eliminate the danger of reaction and allow the “democratisation of the state machine” to be carried through to a conclusion with the establishment of a new state controlled and managed by working people.

If the next Labour government introduced an Enabling Bill into Parliament to nationalise the 200 monopolies, banks and insurance companies which control 80 to 85 per cent of the economy, a decisive blow would be struck against the 196 directors of these firms who are the real government of Britain. By the economic power they wield, they dictate the course to be followed by both Tory and Labour governments. They would be compensated for the nationalisation of their assets on the basis of “proven need.” Such a step, backed up by the power of the labour movement outside parliament, would allow the introduction of a socialist and democratic plan of production to be worked out and implemented by committees of trade unions, the shop stewards, housewives and small businessmen. With the new technology that is on hand, particularly computers, micro-processors, etc., it would be possible both to cut the working day and enormously simplify the tasks of the working class in the supervision and control of the state.

The management of the state machine is at present the closely guarded preserve of the so-called “experts”. But with the cutting of the working day, the working class would be given the necessary time to organise and manage the factories, offices and the state. It is true that they would not be able to dispense with the help of the experts. But once it became clear that almost limitless possibilities would be opened on the basis of a planned economy, there would be no shortage of suitable administrators, managers, and technicians coming forward to put their talents at the disposal of society.

The capitalists would not be able to put up a serious resistance to these measures. Those forces which they relied on in the past—as in the 1926 General Strike when civil servants, students and teachers were used to scab—now look towards the labour movement. The bulk of the civil servants are now composed of low-paid workers who would paralyse any attempt of the capitalists to use them against the working class as a whole. The same applies to the army, which in any case does not have the technical capacity—as the reactionary Ulster Workers’ Strike in 1974 demonstrated—to replace striking workers. A peaceful socialist transformation of society, would be entirely possible if such bold steps were to be taken by a Labour government, however, it is equally certain that the road chosen by the leaders of the labour movement of prevarication and half-measures—will mean enormous suffering for the British working class. Despite the “democratic” mask which the British capitalists have been forced to don over the last twenty years, if their system is threatened they will not hesitate to resort to what Trotsky called that “cold cruelty” which they displayed in the past, both in their dealings with colonial peoples and towards the British working class. Such a terrible danger is undoubtedly posed before the labour movement in the next ten or fifteen years on the basis of a continuation of capitalism. It can only be avoided by the labour movement arming itself with a Marxist programme. A vital component of such a programme will be a clear understanding of the role of the state.