‘Struggle or starve!’ 1932 – when Birkenhead workers beat the means test

To the present generation of workers and young people, the phrase ‘means test’ probably means little. Yet the mere utterance of those words once struck terror into the ranks of the poor and unemployed in 1930s Britain because it denoted a state-enforced programme of savage cuts in the living standards of the most vulnerable. For this reason, in the decades that followed, the mere mention of a ‘means test’ was largely taboo.

Peter Taaffe, Socialist Party general secretary

Not any more! Tory MP Roger Gale, in a recent radio debate with a Socialist Party representative, admitted that following the abolition of the Educational Maintenance Allowance (EMA) the government would seek to cushion the poorest students against economic hardship through the continued and harsher application of a means test, allegedly ‘granting benefits’ according to income.

And this will be applied not just to students but to millions and particularly the unemployed if the government gets its way. It is therefore timely to remind ourselves today of what a means test is and what social and political consequences will result if it is implemented, as the ruling class clearly intend.

One of the most important movements against the means test took place in the autumn of 1932 in the town of Birkenhead. In his book, Idle Hands, Clenched Fists – The Depression in a Shipyard Town, first issued in 1987, Stephen F Kelly recounts the tumultuous events in this town in 1932 and predicts what could happen today. I confess to having a special interest in the events that unfolded then because my own parents were involved in this epic battle.

But the dramatic Birkenhead events were of general significance then and now. I was regaled as a youngster with the details of the mass struggles which convulsed this town. Their generation defeated the means test through what was an uprising of the working class. I learned from my parents that as a result of the workers’ occupation of parts of the city following the brutality of the police, workers set up barricades, established ‘no-go areas’ for the police and raided food shops. For the first time in their lives, “they tasted salmon”. It was a long time before they were able to enjoy again – if they ever did – such luxuries.

Riots on the cards?

The student demonstrations in November and December and the ‘riots’ that followed are an indication that the events of 79 years ago can and probably will be repeated. There were riots in the 1980s – in Brixton, Toxteth and St Paul’s in Bristol.

Moreover, the mass unemployment of the 1930s is being replicated in areas like Merseyside today. 32% of households in Liverpool do not have a single person working! And the right-wing Labour council, yes a Labour council, has just announced 1,500 council staff redundancies. Unemployment, a product of the post-First World War crisis, averaged 10% in Britain and Merseyside even during the seeming ‘boom years’ of the 1920s. But on the back of the world crisis of 1929 it doubled. A fifth of workers were unemployed at that stage.

Those industries such as coal and shipbuilding linked to world trade, which had collapsed, faced a complete catastrophe. Unemployment among dockers rose from 25% in 1927 to almost 40% in 1931! Britain’s shipyards, generally regarded then as the ‘finest in the world’, ground to a halt. In September 1932, according to official government statistics, unemployment zoomed to 62% of shipyard workers, almost treble the national average of unemployment. By this time there was a total of 31% unemployed on Merseyside – a similar figure to that of the US gripped by a terrible and unprecedented ‘depression’. Birkenhead was probably the worst affected part of the region.

By 1932 the relentless unfolding of the crisis came to a head. In this situation the hated means test was enforced. This penalised at least one million people in Britain. Every aspect of meagre working class living standards was ‘checked’ before benefits were given. Workers were forced to sell furniture, pianos and other ‘valuables’ that had been built up in the boom period.

During the first six months of its operation in Liverpool, the Public Assistance Committee (PAC) examined 29,793 applications for benefits under the operation of the means test. In more than 20,000 of these cases the rate of payment was reduced, while in 4,643 cases payment was refused altogether. In the words of one observer “five out of six received a reduction”. Is this the music of the future in relation to what Tory work and pensions minister Iain Duncan Smith intends for those on benefits, including the unemployed, today?

Workers who lived through this period, my own parents included, recounted that they were sometimes compelled to live on stale bread three or four days old, and almost inedible. Children on the ground outside the main Cammell Laird gate on New Chester Road sometimes waited “for their fathers in the hope that there might be a sandwich left in their lunch packs”. Some workers could not afford meat and took to cooking ‘blind scouse’ because it substituted Oxo cubes for meat. The pawnshop did a thriving trade. Tuberculosis, rickets, all the diseases of poverty were prevalent and began to rise.

Why did Birkenhead become a flashpoint for opposition to the means test? There were special characteristics which marked out the town even compared to Liverpool at that stage. The population had doubled to almost 150,000 in just under 50 years. The town required skilled workers for the docks and the shipyard. In Liverpool, where unskilled labour predominated, perhaps unemployment was more ‘accepted’ as part of everyday life, while in Birkenhead this was not so because of previous boom-time conditions.

Dissatisfaction expressed itself in the development of an organised left, led by Communist Party (CP) members like Joe Rawlings and Leo McGree in Liverpool, which particularly concentrated on the issue of unemployment. While the Labour Party and the trade unions were involved, together with the trades council, it was the CP, small nationally with no more than 5,000 members, and no more than 100 members in the town, who played a decisive role. They were able to do this through the local branch of the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement (NUWM), led nationally by Wal Hannington, a member of the party and in Birkenhead by Joe Rawlings.

Jarrow

Jarrow crusade

1932 was a year when there were not just local demonstrations but marchers from areas of high unemployment to London and elsewhere. The Jarrow March of 1936 from Tyneside to London is the most famous. Yet at this time there was also a march to London from Lancashire and Cheshire with some of the Birkenhead unemployed joining in. There was also a Lancashire hunger march in which unemployed members from Birkenhead took part.

A demonstration was set for 3 August, to coincide with the town council’s meeting. The assembly point was the park entrance to the one square mile magnificent heritage of Victorian municipal elegance. At two o’clock, 2,000 people began to assemble in the warm summer sunshine. Interestingly, the tone of the speeches and the declarations and declamations against unemployment have a very topical ring. They declared: “It’s not just the government who are to the blame. Our own council could be doing much more to help the unemployed.” Is this not an earlier reflection of what the Socialist Party is demanding today – in opposition to others tail-ending right-wing New Labour – in fighting not just ‘national’ cuts but those to be implemented by local councils, including Labour?

The demands were quite clear: the abolition of the means test, the extension of work schemes, including building houses, schools and road repairs, a 25% reduction in all rents of corporation (council) houses and no evictions. They marched with clear slogans “fight the means test” and “unemployed workers – struggle or starve”.

The events of August had no appreciable effect on the council. Therefore, at the beginning of September a further mass demonstration was called. This assembled on 7 September to coincide with the next meeting of the town council where the unemployed’s demands were to be heard. 3,000 unemployed once more assembled at the park gates. When they arrived at the town hall they had grown to 5,000 and when a delegation to the town council was not listened to the cry went up: “They’re not interested in us… What are we supposed to do, starve? … Down with the means test!” It was suggested that further talks with the Labour councillors be held but little sympathy emanated from that quarter.

Then on 13 September another demonstration marched to the town hall. Some of the humour of the previous demonstrations was absent as anger and bitterness grew at the refusal to accede to the demands of the mobilised workers. A deputation to the town council demanded that a resolution be moved which insisted that the National Government should abolish the means test. Birkenhead council should follow the example of Sheffield, Wigan and the Vale of Leven in passing similar resolutions. But the majority of the council remained unflinching in their determination to face down the working class.

Outside the council chamber the crowd grew angrier and angrier. Eventually a resolution against the means test was passed to be sent to the National Government and the crowd roared its approval. But the town council, a “reactionary Conservative council” in the words of the unemployed leader Joe Rawlings, had passed a resolution urging action from the National Government but had done nothing to help the unemployed in the town. Even King George V, the symbol par excellence of privilege and power, declared: “If I had to live in conditions like that I would be a revolutionary myself”.

The scene was therefore set for a mass demonstration outside the public assistance offices, organised and publicised by an “army of chalkers”. The slogans were “Struggle or starve” and “Down with the means test!” So big was the crowd that only 8,000 of them were able to pack into the street outside the public assistance office. The police however were mobilising even at this stage for a confrontation.

They attacked the demonstration. The police brutality was the spark to ignite a series of events that were remembered for years to come. That evening, as darkness fell, some of the unemployed went on a rampage that lasted for more than four days. The park railings were broken and used to attack the police. The working class was angry and hungry; they had had enough of the council’s fudging and took action themselves. A group swept down Grange Road, the town’s main shopping centre, shops were smashed; clothes, shoes, food were taken – workers ate food that they had never eaten before and were never likely to in the future. Running battles broke out with the police and the downtown area of Birkenhead was taken over by the working class.

Even the capitalist Times newspaper reported that as the police tried to break up the demonstration: “[They] were met with a rain of bottles, stones, lumps of lead, hammerheads and other missiles … whenever the police were seen sweeping up the streets the rioters disappear into the houses from the windows of which women throw all kinds of missiles … in one street a manhole cover off a sewer was lifted and a wire rope stretched across the street. A number of police fell over this”.

Determination

Here, in a vital region of Britain, in an important town, the elements of a civil war were seen. Indeed, what happened in Birkenhead then is what we saw in the 1980s miners’ strike and on a bigger scale in Argentina where hungry workers raided the supermarkets, occupied factories, etc, in the early part of this century. And Argentina, as well as Birkenhead, could return to Britain today.

Despite all the police efforts “serious rioting” returned again and again. Kelly comments: “Even with their reinforcements, the police could not contain the situation. Around Conway Street and the docks, the working class streets of back to back terraced houses became virtually no-go areas for the police, for the battle to gain a foothold”.

Despite all the police and state intimidation, the working class remained unmoved as Monday night 19 September arrived. Further plans were made for demonstrations to march on the public assistance committee (PAC). However, given the events of the previous days, the PAC, together with the Conservative council and the Chief Constable, were preparing to retreat. This was not before the arrest of Joe Rawlings, Leo McGree and other leaders of the movement.

Special courts were assembled to attack and imprison the unemployed but the mobilisation against the means test continued apace. This time the unemployed did not mobilise at the park entrance. An estimated 20,000 were crammed into the streets around the PAC office, joined by shipyard workers from Cammell Laird who had downed tools to join in. “Nobody in Birkenhead could remember so many gathered in one place”. Even after 4.30pm masses of workers and their families began to join the demonstration and stand alongside the unemployed.

This produced the desired result. At the PAC meeting, almost casually under item 39 on the agenda, the weekly scale of relief for able-bodied single men was increased from twelve shillings to 15 shillings and threepence (76p) and for single women to 13 shillings and sixpence (68p). This was agreed almost without discussion and submitted for ratification to the next council meeting. The members of the NUWM delegation were informed that, having passed the PAC, council approval of the increases was assured.

This was a genuine victory; the increases would help to make life significantly easier for those without work. The rise worked out at more than 25% and represented a considerable improvement in the lives of the unemployed. At the PAC meeting, it was also announced that work schemes would be introduced, and further measures to help alleviate unemployment would mean jobs for many. In addition the council committed itself to lobbying the government for an end to the means tests.

Victory

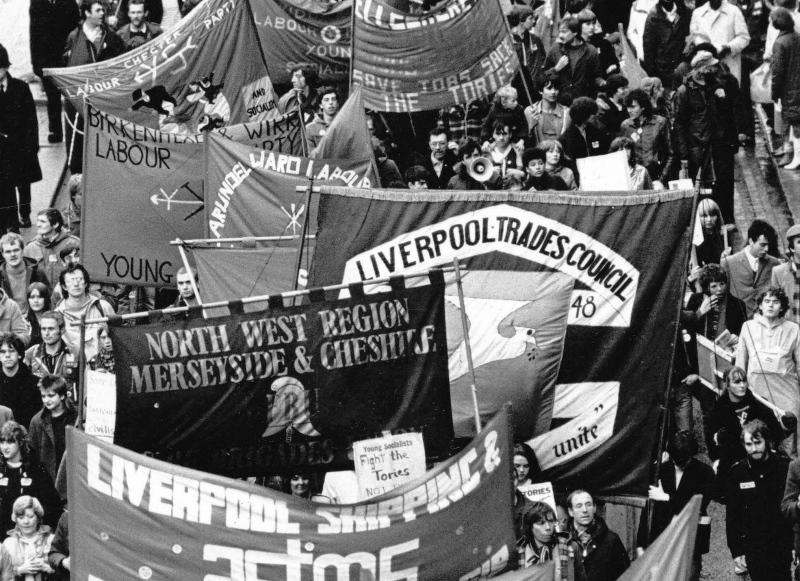

The retreat by the council and, following this, by the government as well was greeted with great rejoicing, as was the equally famous victory of Liverpool City Council against Thatcher in 1984. The announcement of the increase in unemployment benefit produced a huge cheer as people threw their hats in the air and waved their banners. Word of the triumph rapidly spread through the town and this was reinforced by notices in shop windows, followed by the work of the chalkers, etc.

However the broken-down walls, and the damage in the working class areas from the ‘riot’, which was more of a police riot than one of the working class itself, as well as the dismembered railings around the park remained for some years as a symbol of the great struggle that had unfolded in Birkenhead.

Forced through gritted teeth to concede, the capitalists were not prepared to leave it at that. As with the poll tax they sought to punish those who had led the struggle. Joe Rawlings and Leo McGree were jailed along with others. But the Birkenhead victory resounded throughout working class Britain. On Wednesday 21 September 1932 fighting broke out in the Irish working class district of Islington, near Scotland Road, Liverpool as 3,000 unemployed followed Birkenhead’s example. Weeks later in Belfast, in a marvellous movement which involved Catholic and Protestant workers, barricades were set up and the possibility of class unity across sectarian lines was posed. Similar ‘riots’ in Glasgow echoed what had happened in Birkenhead.

Stafford Cripps, the Labour MP for Bristol East, hit the nail on the head when, speaking against the National Government coalition in the House of Commons, he asked: “What are we to say to the unemployed of Bristol who point to Birkenhead? We, who are daily trying to persuade them that they will achieve nothing by rioting, that they can only achieve by constitutional action, are met by the argument: ‘But what is Birkenhead?'”

This is not only a glorious page from working class history, it is a symbol of what can be achieved when working class people decide to fight and throw up from their ranks workers, who go to the end. This present coalition government, if it ever contemplates the past, should tremble at what is coming in Britain if they proceed on their present course.

We, for our part, take great sustenance and encouragement from the battles of the Birkenhead workers and others. The coming struggle will not exactly parallel in every respect how it developed almost 79 years ago on Merseyside. Nevertheless the main outlines of that struggle hold many lessons for us in the battle against unemployment today.