50 years ago, eleven Derbyshire councillors were disqualified from office for refusing to implement the Tory government’s attempts to massively increase rents for council tenants. Dave Gorton, Chesterfield Socialist Party, looks back.

How often have we heard Labour councillors say “there’s nothing we can do” as they unleash another round of cuts? Libraries, care homes, day centres and SureStart closures, privatisation of council services accompanied by thousands of redundancies, and even lowering pay through the disgraceful use of fire and rehire.

It makes a mockery of local government elections if the winners are only prepared to carry out the diktats of the national government. That didn’t have to be the case in the last decade. Labour councils could have united with the workforce trade unions, community organisations and local residents to mount anti-cuts campaigns. These could have been linked across the UK and victories won.

50 years ago, the Labour Party was very different to Keir Starmer’s current version. It had a mass working-class base which the leadership of the party had to occasionally heed. Militant workers in the Labour Party were to the fore in the huge struggles in the 1970s. Labour is now transformed into an openly capitalist party, no longer with a working-class base.

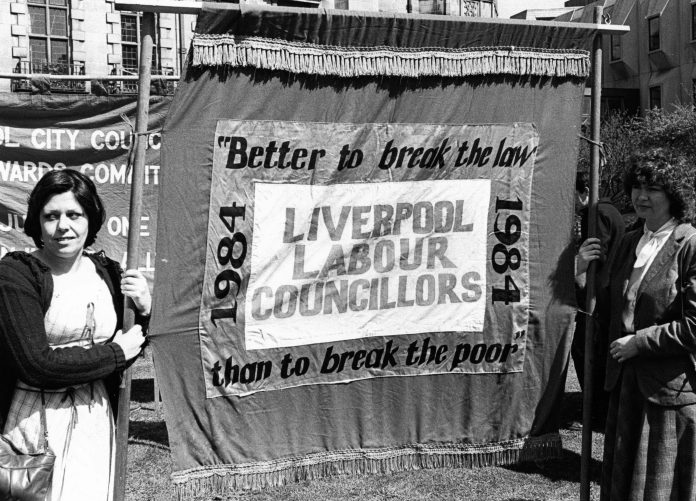

Liverpool council defeats Thatcher

In the 1980s, led by Militant (the predecessor of the Socialist Party), Liverpool’s Labour city council conducted a huge struggle to win back funding stolen by Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government away from the provision of local services. Although every other Labour council barring Lambeth fell away, the council was able to win extra finance leaving a legacy of over 5,000 new council homes as well as building leisure centres and parks.

A decade earlier, in Clay Cross, a small north east Derbyshire town of less than 10,000 inhabitants, another Labour council held firm against Tory cuts, at great personal cost. Those Labour councillors were made bankrupt for their challenge but none of them regretted their stand.

Clay Cross is an area that thrived on coal. By the end of the 1960s, however, pit closures had a devastating effect. Within a decade, all 14 pits within a five-mile radius of Clay Cross had closed. Unemployment rocketed from 6% in April 1969 to 20% by the beginning of 1972.

Into this decline, the Tory government introduced the 1972 Housing Finance Act, which forced councils to increase rents to a level comparable to the private sector. The majority of the UK’s council housing stock was under Labour authority control as the Tories had been decimated in the 1971 and 1972 local elections. To implement the Act, the Tories needed Labour councils’ help, and most obliged.

Labour-led Clay Cross Urban District Council (UDC) declared it would not implement the Act: “On this Council we like to think of ourselves as basic socialists. We regard housing here as a social service, not as something the private sector can profit from”, said Councillor Arthur Wellon.

The council had a proud record of defending working-class people and seeking to relieve deprivation.

The list of benefits they introduced was impressive: free travel and TV licences for pensioners, playgroups in the school holidays, the building of a swimming pool and three ‘Darby and Joan’ clubs for older people.

When the Tory government stopped free school milk, Clay Cross UDC operated its legal right to use a penny rate to continue to provide milk. When the councillors realised money would run out two months early, they circumvented the problem by increasing the never-used ‘chairman’s allowance’ from £25 a year to £385, and used that!

The council expanded its direct labour force to provide work to unemployed miners and paid them a living wage.

Slum clearance and new houses at low rents

But the real issue in Clay Cross was housing. Over 20% of the stock in the 1960s was slums. By 1971, the council had replaced over 550 houses. It was a costly programme as the slums had to be bought before they could be demolished and new land had to be purchased. However, council rents remained the lowest in the county.

When three councillors got cold feet in 1970 and jumped ship to form the Residents’ Association, Labour won all three seats on a turnout double the national average for urban elections. The Sheffield Star said: “Democracy comes in many forms; some less satisfactory than others”!

The 1972 election saw Labour win all four seats against the Residents’ Association. What became the renowned ‘first XI’ were in place: ten men and one woman prepared to stand up for their socialist principles. They held firm.

In Clay Cross, the tenants weren’t fighting their local authority, it was local councillors leading the opposition. When the government ordered an audit of the Clay Cross books, the deputy district auditor was met by the entire 100-strong workforce of the public works department taking an hour off work to greet him with a rousing chorus of the Red Flag!

3,000 people from all over Britain descended on Clay Cross in December 1972 for a solidarity march. The Militant newspaper (the forerunner of the Socialist) at the time noted “the solid support of the local tenants was indicated by the fact that the march increased in size five times over as it passed through the council estate”.

Councillor Graham Skinner spoke to The Militant: “We fully understand the Act… we expect there is a possibility of going to jail. But we are… not carrying out Tory measures.”

There was a solidly supported six-week rent strike before focus switched to the law courts. In July 1973, the High Court found the councillors guilty of “negligence and misconduct” and fined the eleven a total of £6,985 (plus £2,000 costs) and disqualified them from office.

In the 1974 by-elections to replace them, ten out of the eleven Labour candidates (‘the second XI’), standing on the record of their predecessors, were successful. The eleventh lost by two votes.

Local government reorganisation

The housing commissioner sent in by the government failed to collect a single penny in increased rents in six months and it was only local government reorganisation later in 1974 that ended the conflict with the abolition of the Clay Cross UDC. The incoming Labour administration in the new council imposed rent increases.

Today, Clay Cross has a Tory MP – unthinkable in 1973. The ‘village’ has grown with a Tesco superstore at its centre, in the process driving out local small businesses. There has been a huge increase in private housing on its outskirts but its social housing stock, lower in number now, is operated by an arms-length management organisation and young people, in particular, find the lack of affordable housing a big issue. If Labour had backed, instead of chastising, the Clay Cross councillors, the picture may have been very different.

There is no hope of Labour under Starmer changing its pro-big business policies. Workers and tenants need a new party of the working class, built on the ideals of public ownership and social housing, which will challenge the capitalist system that confines the majority of the population to poverty and hardship.