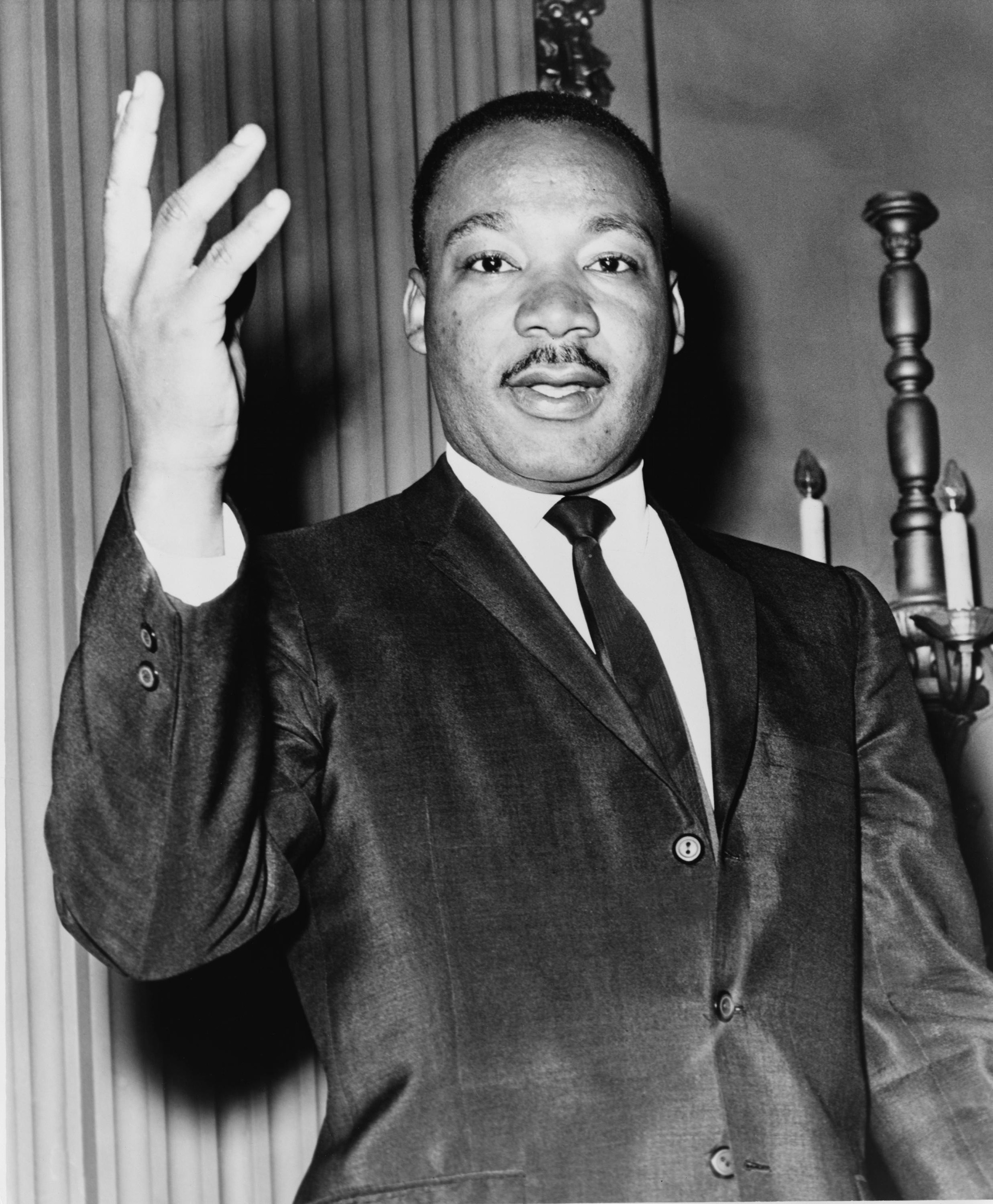

28 August marks the 60th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington by the US civil rights movement, at which Martin Luther King made his famous ‘I have a dream’ speech. To mark the anniversary, we republish a shortened version of an article about Martin Luther King, written by April Ashley, Unison national executive council, black members rep (female) (personal capacity), and originally published in the Socialist in April 2018 to mark the 50th anniversary of his assassination.

Martin Luther King Junior was shot and killed on 4 April 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee, while supporting striking sanitation workers.

He is now portrayed as a safe, noble and worthy figure in order to blunt his quite radical message, but at the time of the civil rights movement he was hated and feared by the Democratic Party in government.

The Democratic Party attempts to perpetuate the myth that it is the party of civil rights and that there is a straight historical line from Martin Luther King to Barack Obama. But King’s radical vision and legacy is a world away from the capitalist establishment of the Democratic Party.

King, a Baptist minister, was the most important leader of the civil rights movement.

One-third of the southern protest leaders were preachers. The churches were the only places where the Black community could freely congregate, and where all the issues facing Black workers and youth were discussed. That is why non-violence was the main strategy adopted in the early period of the civil rights movement.

Radical

But King’s advocacy of mass non-violent civil disobedience was radical and courageous at that time, in contrast to the more moderate leadership of the traditional Black organisation NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) which focused on legal action.

King and his organisation – the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) – organised mass demonstrations and boycotts against racial segregation, for voting rights and equality of employment. Black people faced down police attack dogs, fire hoses, police beatings, mass jailing of students, death threats and bombings.

The mass movement caught fire across the whole of the southern states. The struggle in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 was a key battle with up to 3,000 students jailed as they continued the battle on the streets.

Peaceful protesters being savagely attacked was seen live by millions of viewers on the TV. It shocked the nation and inspired the black freedom struggle in the northern cities.

It was pressure from the mass movement below that prompted the Democratic governments under John F Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson to pass civil rights legislation banning racial discrimination in voting and public facilities.

This was a triumph for King and the whole civil rights movement after years of struggle. As King said in his letter from Birmingham jail: “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

King had many discussions with John F Kennedy on civil rights for black workers, and tried working within the confines of the Democratic Party to affect change. But this was ineffectual. It was the mass demonstrations like the march on Washington for jobs and freedom where King delivered his iconic ‘I have a dream’ speech at the Lincoln memorial in 1963, which forced change.

But the civil rights movement didn’t just stop in the Southern states and King’s ideas were evolving.

Black migration

King travelled to northern cities where the generation of black workers who migrated to the north in the 1920s and 1940s, especially after World War Two, to escape the rural poverty, white supremacy violence and Jim Crow (discriminatory laws), still faced segregation, police violence, poor housing, mass unemployment and poverty.

There were huge uprisings in Watts (Los Angeles), New York, Detroit and every major city with black workers struggling for freedom against racial discrimination and poverty. The movement raged across cities from the mid-1960s to early 1970s and evolved into the ‘Black Power’ movement.

King’s tactic of non-violent civil disobedience was questioned by the many black workers and particularly black youth facing horrific police brutality. The Black Power movement was also inspired by the movements against colonial oppression and imperialism in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean.

The Black Power movement with people like Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) provoked intense debate in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) on the questions of integration, consumerism, capitalism, imperialism, militarism and war.

The time spent in northern cities among radicalised workers and young people and their anti-war mood had a profound effect on King.

King eventually came out against the Vietnam War, which put him in conflict with the Democratic Party which had started the war and continued it under the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

King was deeply disturbed by the increasing death toll of US soldiers and recognised that black soldiers were disproportionately placed in combat units. Between January and November 1966 almost 25% of army casualties were Black. In addition, half a billion dollars were diverted from community action programmes to war spending in Vietnam.

This was a huge break with the Democratic Party. The mass media, which now lauds him, denigrated and hounded him for demanding the withdrawal of American troops. President Johnson referred to him as “that goddam nigger preacher.”

King’s anti-war activism deepened his radicalism and he began to question capitalism.

He said in August 1967: “We must ask the question: ‘Why are there 40 million poor people in America?’ And when you begin to ask that question, you are raising a question about the economic system, about a broader distribution of wealth. When you ask that question, you begin to question the capitalistic economy.”

He increasingly began to turn his attention to problems of economic justice and inequality – as, although there was no longer formal segregation, the condition of black workers was still abject poverty. He believed a serious battle against poverty and oppression was necessary.

In 1968, King launched the Poor People’s Campaign. He hoped to go around the country assembling a “multiracial army of the poor” to march on Washington to abolish poverty in the US and internationally, and demand that the money being spent on the Vietnam War be redirected to provide jobs and income for the poor.

The Memphis sanitation workers’ strike of 1968 epitomised the struggle for economic justice – to end the poverty wages earned by working people. As King said: “What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t have enough money to buy a hamburger?”

King politically and organisationally understood the link between the labour and civil rights movements. The ‘captains of industry’ and big business opposed both labour and civil rights, holding down wages and violently attacking strikes for union representation and better working conditions.

The US capitalist class and their political representatives have always used racism and sexism to divide the working class and deny human rights, economic justice, and social mobility to the black masses, immigrants, and women.

It was during the sanitation workers’ strike after a demonstration through the city that King was shot dead on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

It was a severe blow and the mass movement was not sustained either by the official reformist civil rights organisations or by the Black Panther Party, which as well as being subject to brutal oppression and assassinations by the FBI, made strategic mistakes.

Black Lives Matter

Today, Black young people in the US have continued the black freedom movement through the Black Lives Matter (BLM) demonstrations.

Black workers still suffer high levels of unemployment, poverty and low-wage jobs, and poor housing. 50 years after the assassination of Martin Luther King and after a black US president, little has changed for the overwhelming majority of Black youth and workers.

The BLM movement has emulated the mass civil disobedience of the civil rights movement of 1950s and 1960s and the movement has been echoed internationally. But its programme is limited.

It needs to go further and draw some of the same conclusions of Martin Luther King that in order to seriously challenge structural racism and racist attitudes we need to build a mass movement of all those exploited and oppressed by capitalism. We need to create a new society that can end poverty and discrimination, a socialist society.