130 years ago, in the second half of 1893, 300,000 miners across Britain’s major coalfields were locked out for four months, with employers demanding a 25% wage cut. Workers resisted, different methods of trade union organisation were put to the test, and the forces of the capitalist state showed their repressive role. Iain Dalton, Socialist Party Yorkshire regional secretary, revisits the events.

The employers had been forced to concede a series of wage increases amounting to 40% since 1888, as a wave of industrial militancy swept Britain during a period known as ‘New Unionism’. But into the 1890s, as the economy and coal prices declined, the bosses wanted to take back what had been given.

As the coal trade recovered following the long depression of the 1870s and 80s, the then county-based miners’ unions were split over the best methods to defend wages. Some of the larger mining areas, such as Durham, Northumberland and the majority in South Wales, favoured what would today be called ‘partnership’ with the employers and agreed a sliding scale of wages that would decrease when coal prices dropped, and increase when prices went up.

In contrast, the unions that formed the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB, later the National Union of Mineworkers), led by Ben Pickard the general secretary of the Yorkshire miners, instead demanded a ‘living wage’ and an eight-hour working day.

The MFGB was the third attempt at forming a national miners union, with others going back to the Chartist revolts in the 1840s.

It was the fight to win the ‘living wage’ demand in particular, that led to the industrial militancy of the MFGB and its leaders. With illusions in the Liberal government of the time, the MFGB pursued their eight-hour day demand through parliament, as Pickard later explained: “Strikes and lockouts and tumults do not hold with me, and never have until they were forced upon me…”

When the economy moved into recession, and the selling price of coal dropped, the wages of miners in the non-federation areas began to be reduced. Failing to get a coordinated response with the non-federation miners’ organisations, the MFGB leaders instead initially put into practice a strategy known as ‘playing the pits’.

‘Overproduction’

This strategy was based on the idea that overproduction of coal was a key factor in the selling price of coal dropping, so if miners took a week’s holiday from work at the same time, then that would reduce the output of coal and exert upwards pressure on wages. Of course, this theory misses the fact that employers can increase the rate of exploitation by holding down wages to increase their profits.

Despite the strategy’s limitations, the fact that the MFGB was able to carry out a week’s stoppage across the federated area it covered, even with a significant number of miners not being ‘financial members’ of the unions (ie not paying union subs), highlighted their potential power. As Pickard explained in a letter to a MFGB special conference: “It is quite clear that if the men will stop for one week, they will stop for two, three or more weeks, as they may require.”

This display of strength held the owners in the federated area back for over a year before they again raised the potential for wage cuts. In contrast, miners in Durham who refused to accept further wage cuts were locked out for twelve weeks, ultimately succumbing to the cut.

As 1893 began, smaller coal owners attempted to implement cuts. Employers issued an ultimatum for a 25% cut and the lockout began at the end of July. Half of the 300,000 affected miners were MFGB members.

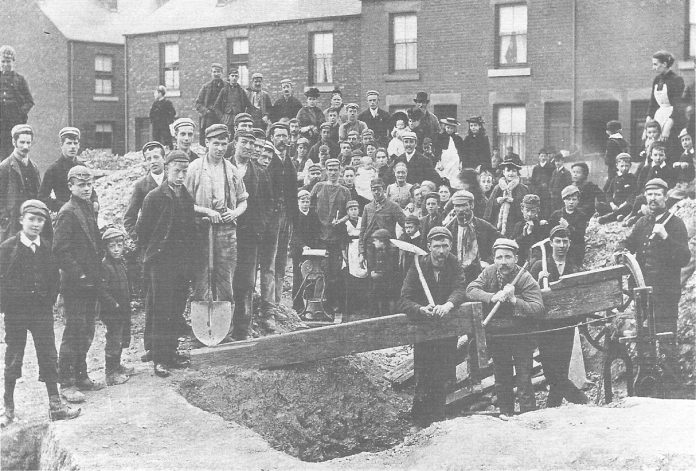

Several weeks into the dispute, any rumours of coal being loaded or men working underground, was met with anger and mass pickets outside the respective pits.

On some occasions, these situations were easily resolved, such as at Rylands Main near Barnsley, where the colliery manager invited a workers’ deputation to inspect the site. At Waterloo colliery near Leeds, a crowd of 5,000 gathered which effectively stopped deputies from going underground.

However, a number of colliery owners were determined to try to break the strike. At Rockingham colliery, again near Barnsley, a crowd of up to 3,000 miners was unable to get guarantees from the owner and took action themselves to stop the coal, including stoning men loading wagons, setting the coal heap on fire, and slipping the brakes of one of the wagons.

Some of the more well-connected owners called in the police or the military to help defend their profit interests. During the first weeks of September, 400 Metropolitan Police and even more infantry and cavalry from the armed forces arrived in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Miners who went to Barrow colliery near Barnsley found themselves confronted with police armed with cutlasses.

On 7 September, events reached their highest pitch, when the Riot Act was read out after crowds had surrounded two pits: Ackton Hall colliery near Featherstone and New Watnell colliery near Nottingham. The events outside Ackton Hall colliery have become known as the Featherstone Massacre, after two men were shot dead (one of them simply walking nearby), with dozens others injured.

The establishment rallied to defend the shootings. Even the Liberal press – such as the Guardian – denounced the strikers, with their article on Featherstone stating: “For the sake of the miners and of trade unionism itself, we hope that every repetition of these blundering crimes will be repressed with more common sense than when soldiers were helplessly looking on for want of a magistrate to read the Riot Act.”

The inquest held in Featherstone for James Gibbs, one of the men killed, found the authorities responsible for his death, in contrast to the inquest into the death held in Wakefield. Eventually the campaign won compensation for the two men’s families, with Asquith, the Liberal home secretary who had dispatched the troops to the area, becoming known to miners as ‘Bloody Asquith’. The newly formed Independent Labour Party made the ‘massacre’ a cause célèbre in the labour movement.

This wasn’t the only confrontation that took place, with others as late as the end of October at Ripley in Derbyshire.

The striking miners received overwhelming public support, raising funds to support the miners and their families. Radical newspaper editors opened lists for subscribers, and local co-operative societies donated cash and food.

A decision at the end of September to allow miners to go back to work at the old rates, with them paying a shilling a day levy to support miners still locked out, further alleviated the financial distress.

This strengthened the miners’ position, and ultimately forced the government to step in to resolve the dispute. The miners returned to work on 17 November without having to concede any loss in pay, with a conciliation board due to meet in February 1894 to discuss any changes to wages.

In the end, a 10% reduction in wages was agreed from July 1894 as the only reduction miners in the federated areas were subjected to before wages began to increase towards the end of the century.

This was a significant victory against the backdrop of defeats and disintegration being suffered by many of the new unions at this time, where the state machinery had similarly been lined up to crush the workers and their trade unions. It consolidated the MFGB as one of the most powerful trade unions in the country.