Hugo Pierre, Socialist Party National Committee

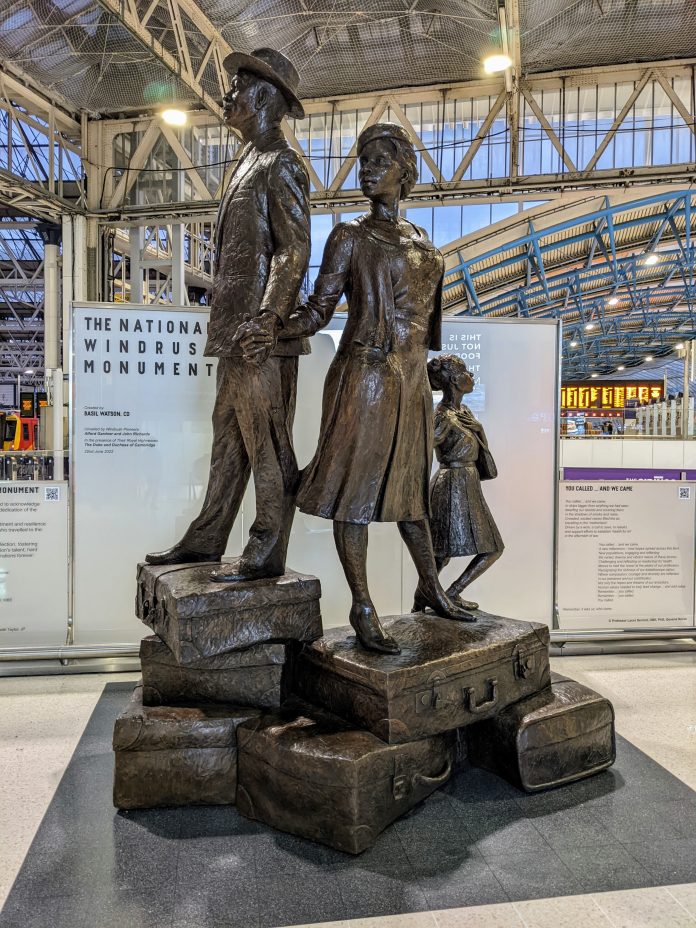

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the Empire Windrush ship docking at Tilbury, Essex, in 1948. That marked what is considered to be the beginning of modern immigration into the UK from the former colonies, particularly of Black workers from the West Indies.

The Tory party is deeply divided on many issues, including immigration, with the cabinet currently a hostage to their extreme right wing on this issue. The Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, is pushing her policy of using boats in the opposite way the Empire Windrush was used in 1948 – in this instance, to moor them off ports and house refugees.

She is also still pursuing the policy of flying any migrants that use ‘illegal’ routes of entry to Rwanda. Her own backstory reveals that her father fled from the land of his birth, Kenya, and was allowed to migrate to London because he held a British passport. This allowed entry under the long-since abandoned Nationalities Act 1962, even though this was amended in 1968, just before he arrived.

Post-World War Two

After World War Two there was a substantial rebuilding job in the UK, in the cities and in industry. But this coincided with a great shortage of labour. 100,000 Polish workers and their families, recruited through a European Voluntary Workers scheme of displaced eastern Europeans, and free transit for Irish workers, were used to fill the gap.

At the same time, the landslide Labour election victory of 1945 posed the fear of revolution for the ruling class. They were prepared to make substantial concessions to save their system. The nationalisation of key industries and infrastructure, and the establishment of the welfare state, were a major encroachment on the bosses’ source of profits and power.

In the immediate post-war years, no call was made to the colonies for workers, particularly from the West Indies and Africa, although Labour introduced the Nationalities Act in 1948 that gave to anyone born in the colonies the right to live and work in the UK.

Many of those that set sail on the Windrush from the Caribbean quickly found work. Immigration from the West Indies that followed was a trickle until the mid-1950s, when the US imposed stricter immigration controls.

Even then, the Conservative governments of the 1950s were actively looking at ways to reduce immigration from the West Indies. They followed on from an initial Labour cabinet inquiry to try to find ways to limit ‘coloured’ migration into Britain. In the end they limited their restrictions to bureaucratic methods rather than legislation. Legislation at that stage would have inflamed the rise of national liberation movements, especially in Africa but also the Caribbean.

Immigration from the West Indies hit a peak in 1956-57. Housing shortages leading to discrimination by landlords was a common situation faced by many. A ‘colour bar’ also operated in many industries. Those with skills and professional qualifications often could not take up those professions and were forced to work in lower-skilled occupations.

The immediate post-war economic upswing was coming to an end by the late 1950s. In the late summer of 1958, Blacks were attacked in Nottingham and more infamously in the Notting Hill area of London. The Notting Hill riots were almost certainly inspired by supporters of Oswald Mosley, leader of Britain’s fascist Union Movement, even though the police reported to the Home Secretary that racism was not the motivation for the riot.

Black resistance

However, Blacks were no longer willing to tolerate this level of violence and organised to resist. Some attempted to mobilise the local trade unions. Unfortunately, the response of the trade unions was weak.

A delegation of Black workers approached the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to organise, in effect, an anti-racist rally in the local area to support the Black community, oppose further racist attacks, and to bring together trade unionists in their support. Black workers were also urged to speak to individual trade union branches, to put their case against exploitation both ‘in the colonies’ and against the rent-racketeering endemic in London at the time. This call to action, if followed by the TUC, could have created a force in local working-class communities.

The ruling class reacted to these events with restrictive racist immigration controls, with the Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962 introduced by the Tories.

Black workers were fighting for jobs and recognition by the trade unions. In the 1960s ‘colour bars’ operated in many jobs. Workers would often face restrictions on promotion, or were tasked with the most menial jobs. Many fought back using protest, boycotts and other methods, often without official trade union backing.

The Labour government was forced into action, introducing its first Race Relations Act in 1965. But racism was whipped up further by their Commonwealth Immigration Act 1968, specifically designed to limit the potential influx of Kenyan Asians. Right-wing Tory politician Enoch Powell made his infamous ‘rivers of blood’ speech, calling for a halt to further immigration and the repatriation of ‘non-whites’ to their country of origin.

There have been many new controls since the Immigration Act 1981, which completely revoked the right of a member of the former British ‘colonies’ to live in the UK. Both New Labour and the Tories have also cynically used immigration controls and asylum seekers as a proxy for continued use of ‘divide and rule’. In the Tories case, to promote cuts and austerity, and while Labour sought a diversion from fighting cuts and austerity.

The most recent legislation, introduced by the Tories, along with the destruction of boarding cards for those that travelled to and settled in the UK before 1971, led to the Windrush scandal, where Black workers with the right to live and work in the UK were denied jobs, medical care, and some even lost their homes.

The struggle against racism

The situation today is very different from that facing the Windrush generation, or even those who became active in the 1990s and 2000s. Trade unions have been forced into action on the cost-of-living crisis. A new generation of trade unionists and reps are being recruited in many workplaces, in many cases with Black workers to the fore.

The trade unions, whilst not perfect, nearly all have policies opposing racism and racist immigration controls. The TUC also passed a motion, campaigned for by Socialist Party members, in 2018 calling for racism to be fought not just as an ideology but by winning workers away from these ideas with a campaign to link this with the demands to meet the needs for jobs, homes and proper services.

Jeremy Corbyn’s general election manifesto of 2017, with all its limitations, raised the consciousness of many that there was an alternative to capitalism and its racism and division: socialism. This had a dramatic impact on Black workers, with a greater percentage turning out to vote Labour than in previous elections.

The response to the George Floyd murder in the US during the Covid pandemic lockdown in 2020, when demonstrations were effectively illegal, also shows that a new layer want to fight for their future. Black youth who had never taken part in any demo turned out with their own home-made slogans for ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests.

The battle for ideas to end racism will be a struggle for the new layers that will be drawn into it. But a core will be won to the idea quickly that the struggle for a socialist society is the only way to end racism once and for all.