Scott Jones

The peaceful picture postcard white sands and turquoise seas of Caribbean island nation Grenada were dramatically disrupted 40 years ago on the morning of 25 October 1983, when US troops invaded.

Grenada, known for its spice plantations, and sitting off the coast of Venezuela, with a population of 90,000 at the time, is described by Grenadians as “just south of paradise, just north of frustration.”

Much of that historical ‘frustration’ experienced by the poor, former British slave colony turned to hope when, in 1979, five years after independence, the left-wing New Jewel Movement led by Maurice Bishop came to power establishing the People’s Revolutionary Government.

Bishop said: “We are a small country, we are a poor country, with a population of largely African descent, we are a part of the exploited Third World, and we definitely have a stake in seeking the creation of a new international economic order which would assist in ensuring economic justice for the oppressed and exploited peoples of the world.” This was echoed on the streets by ordinary people in Grenada, as one journalist said: “This is the first time I’ve seen the fellows on the block controlling something.”

Gains for ordinary people

The new government set about launching literacy campaigns and allowing the learning of Grenadian Creole in schools. Medical consultations were made free and milk was distributed to children and pregnant women. Financial loans, equipment for farmers, and agricultural cooperatives were provided. Unemployment fell from 49% to 14%. The government also invested in infrastructure, building new roads, upgrading the power grid and construction of an international airport, to expand trade and tourism.

The building of the airport was aided by Cuba, which also provided Grenada with doctors, and the two countries formed close ties. Capitalism had been overthrown in Cuba in 1959 by the revolution led by Che Guevara and Fidel Castro. Its support for the Bishop government provoked the anger of the United States, which did not want another Cuba on its ‘doorstep’, nor for the ideas and actions of Grenada to spread to larger Caribbean countries like nearby Trinidad and Tobago or Jamaica.

US president Ronald Reagan claimed in early 1983 that aerial photographs showed the “the Soviet Cuban militarisation” of the island, but even his own defence officials denied that the airport’s 9,000-foot runway was ever, or could ever, present a military threat to the security of the US. The British company Plessey was also contracted to build parts of the new airport and it too denied that its building specifications were remotely like those for a military airstrip.

But the pretext for US intervention came in mid-October when a power struggle between factions of the New Jewel Movement and the army erupted, and led to the arrest and execution of Bishop and members of his cabinet, with deputy prime minister Bernard Coard and General Hudson Austin taking the reins. Reagan ordered an invasion, which took place days later with the aim of “forestalling chaos”.

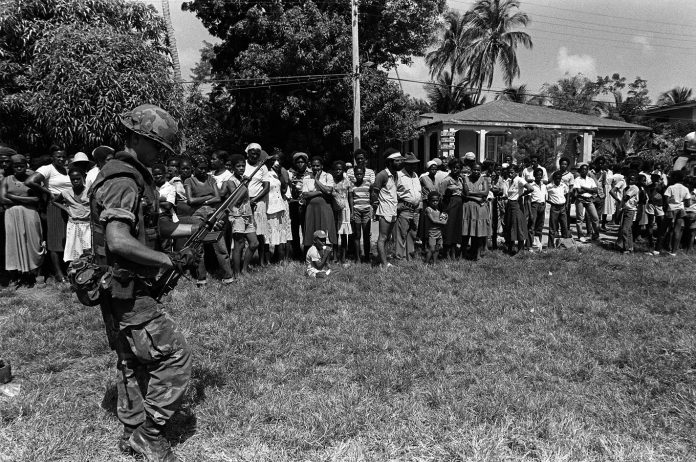

Yet during the invasion – called ‘Operation Urgent Fury’ – US military and aircraft bombed a hospital in the capital St Georges and almost a hundred people were killed overall, including Cuban workers and soldiers, and US troops themselves. There were also hundreds wounded, and Grenadian government supporters, called “leftist thugs” by Reagan, were arrested and detained by the US ‘peacekeepers’.

The US relied on its ally Britain, and Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher, to install a new regime – Grenada was a part of the Commonwealth – led by the Queen’s representative on the island Governor-General Paul Scoon, who it was later revealed had worked with the US to undermine the regime before Reagan’s coup. This was despite Reagan admitting in his autobiography that he had invaded without even telling Thatcher who had some uncharacteristic reservations. So much for the special relationship! And proof there’s no honour among thieves.

Reagan exaggerated the scale and success of the coup, handing out 8,612 medals, many of them to desk officers who never went anywhere near the island. He absurdly declared: “Our days of weakness are over!” after occupying an island of just 90,000. There were plenty of weaknesses too and against a bigger army it could have led to another ‘Bay of Pigs’ style disaster like in Cuba in 1961. The invasion force used photocopies of tourist maps and one officer had to call his base in North Carolina from a pay phone to request air cover due to communication failures!

But Reagan used the invasion to bolster justification for US intervention elsewhere, escalating attacks on the left-wing Sandinista government in Nicaragua after Grenada.

The Socialist Party, then Militant, supported the reforms of the Bishop government and opposed the US-led coup that intervened in the interests of local capitalists, and which installed a new regime with American bayonets. We joined protests outside the US embassy in London and in Hyde Park, pointing out: “The invasion has ‘internationalised’ the Grenada issue in the minds of many Caribbean workers”, and we called for “a Federation of Democratic Socialist States, as an answer to the impasse of capitalism and all its social ills.”

The New Jewel government in Grenada had mass support because of reforms and measures it introduced that improved ordinary people’s lives. But as we said in the pages of the Militant at the time: “Bishop’s government was not one based upon an active and healthy regime of workers’ democracy, with committees of workers constantly checking, discussing and controlling the functions of the state. The key sectors of the economy remained in private hands, despite the reforms.”

This task, struggle and programme remains the same today. Grenada is now one of the poorest countries in the Caribbean, one of the poorest regions in the world. In the Caribbean, like workers and the poor masses around the world, revolutionary socialist and working-class parties are needed to fight poverty, capitalism, imperialist wars and invasions, and for socialist change.