Today, nearly one in five councils are at risk of bankruptcy, according to the Local Government Association. Twelve have issued a ‘Section 114’ notice in the last three years – declaring that they will limit spending to ‘statutory services’ only. Significant recent examples are Europe’s biggest local authority Birmingham City Council, and Nottingham City Council. Thousands of jobs are under threat.

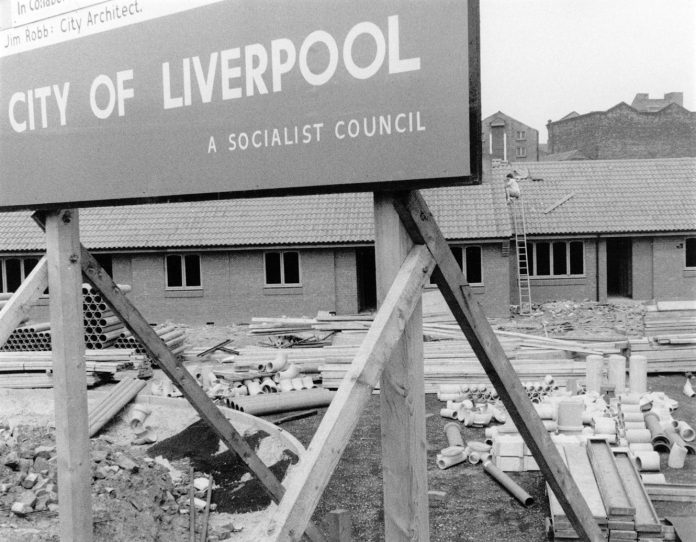

In the 1980s, Liverpool Labour councillors, faced with Tory central government cuts and a financial hole left over from a previous Liberal administration, fought back and won. Working-class people in the city today still benefit from the homes, leisure centers, schools and parks the council built. Dave Walsh, Secretary of Liverpool Trades Union Council, and one of three hundred apprentices taken on by the council in the 1980s, looks at the lessons of Liverpool’s Militant socialist council.

The Labour council in Liverpool was elected in 1983, but the conditions which led to its victory had been developing for 20 years. Liverpool’s economy boomed post World War Two, but started to decline in the late 1960s.

Containerisation destroyed thousands of jobs on the docks, up until then Liverpool’s biggest employer with around 100,000 dockers. De-industrialisation in the 1970s saw many large manufacturers move their production overseas. Liverpool, being an industrial city, was hit hard.

Many of these companies had received public funding which paid for the machinery they were taking out of the country. The city’s population collapsed, from 740,000 in 1960 to 480,000 in 1980. Those leaving tended to be younger and in good health, with skills or an education; this left the city disproportionately older, sicker and poorer.

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government introduced massive austerity cuts across the public sector. Her government also changed the local government funding formula, reducing government grants that had previously redistributed funds to poorer cities with greater social need like Liverpool.

In 1980, the Liberals took control of Liverpool council with the support of a few Tories. This administration went even further than Thatcher with an underspend which saw them send money back to central government! The Liberal leader Trevor Jones was knighted in 1981.

When the Liberals lost control in 1983, they left £10 million of unallocated cuts, which equated to 2,000 redundancies. You might wonder how a city with such poverty and deprivation had a Liberal-Tory administration? But Liverpool’s working class had experienced Labour administrations, elected on radical manifestos that failed to deliver, resulting in apathy.

Labour was then a workers’ party but with a pro-capitalist leadership controlling the levers of power. Mass participation of workers and trade unionists in its structures was able to apply pressure and influence party policy. Members of Militant (the Socialist Party’s predecessor) campaigned within the Labour Party for a Marxist programme and to transform the democratic structures to make the leadership fully accountable to members. In the conditions that existed in Liverpool, these ideas became increasingly popular. By the early 1980s, Militant was the dominant force within Liverpool District Labour Party.

In May 1983, Labour gained 12 more councillors and a majority. At that time, there were few expectations beyond the activist layer that this Labour administration would be any different from the others; but those thoughts were short-lived. Immediately after being elected, the Militant-led council cancelled the £10 million of unallocated cuts and set a needs-based budget.

Instead of more redundancies, every department saw increased funding based on its needs. Six new nursery schools were built, and five new sports centers – all in working-class areas. Social services, schools, and youth and community services all got extra funding, enabling them to employ more staff and expand vital, frontline services.

In September, the council took on almost 100 apprentices in various departments, I was one of them. These jobs were a lifeline to many young people like me, in a city gripped by hopelessness. In housing maintenance where I worked, there was new funding for planned maintenance projects. This was much more effective than the previous reactive maintenance process which required tenants to phone to report a repair and then wait for months on end for a response. Planned maintenance allowed whole estates in areas that had been neglected for years to be modernised in one fell swoop; providing improvements such as new roofs, windows, bathroom extensions and central heating.

The first site I was sent to at the end of 1983 replaced metal-framed, single-glazed windows with uPVC double glazing. I’d never even heard of uPVC frames before then. The properties were also fitted with gas central heating. The residents told us their homes went from being ice boxes to warm and comfortable overnight. The council also began to deliver on its main manifesto pledge, to address the city’s housing crisis, clear slums and build new council houses.

The councillors were met with resistance from a senior layer of council management. The director of finance told councillors he was unable to release the city’s reserves because of his fiduciary responsibility to the city. Previous Labour administrations had hit this barrier before and used it as an excuse to break their promises. But the Militant-led councillors were ready, and told all the directors they must follow the instructions of the democratically elected council or resign. All the directors fell in line.

Liverpool residents were noticing the difference, but so was the capitalist class. The media by this time was full of ‘red scare’ stories, with headlines accusing the council of reckless spending that risked bankruptcy for the city. But Militant was well organised. Hundreds of volunteers delivered hundreds of thousands of leaflets to homes explaining they were using reserves and prudent borrowing to fund vital services, clear slums and build new homes, and the aim of the campaign was to win back funding that had been stolen from the city by the Tories. This was the battleground during the local elections of May 1984.

The media’s biased coverage did result in an increased vote for the Liberals and Tories, but their vote was buried under an avalanche of working-class votes for Labour.

Shockwave

The victory sent a shockwave across the establishment and the following month the Tories sent their environment minister Sir Patrick Jenkins to the city. He was taken on a tour of the city’s worst slums by councillors. Tony Mulhearn, one of those councillors, a Militant member and Chair of the District Labour Party, often described Jenkins as an old money, patrician Tory. Jenkins later said at a press conference, “I have seen housing in Liverpool the likes of which I have never seen before”. Tony often remembered to people how the shock was etched on Jenkin’s face at the site of these terrible slums.

The Tories, who were fighting on two fronts with the 1984-85 miners’ strike still raging, were forced to retreat and released £30 million of funding (£120 million adjusted for inflation). This money allowed the council to continue to implement its manifesto. Other Labour councils, seeing the victory, joined the campaign. This became known as the ‘The Rate Capping Rebellion’. In March 1985, the miners’ strike came to an end. The Tories now turned to concentrate on the council rebellions. Soon after, district auditors began legal proceedings against councils refusing to set a compliant rate.

The Shop Stewards’ Committee at Liverpool Council was well organised, with experienced Militant organisers in leading positions. I remember as an apprentice we were moved around different projects for experience, but the one constant was at every site there was a shop steward’s report every Monday morning, reporting back from the previous Friday’s Shop Stewards’ Committee.

Not all the shop stewards were Militant members, but they were militant workers, elected by us in the workplace, they helped shape the strategy and tactics of the joint union campaign and they relayed information to the workforce very effectively.

When the council took the tactical decision – aimed at pressuring Thatcher’s government to release vital funds – to distribute technical ‘redundancy notices’, it was understood and supported by the majority of council workers as a formal procedure to release short-term funds. Not a single council worker was made redundant during this period.

Eventually, with the Tories still refusing to provide the additional national funding needed, Liverpool council went outside the normal borrowing procedures and took out loans directly with banks. These were secured on lower interest rates than if they had gone through the usual government channels. This is how the council continued its campaign, clearing slums and building new homes and communicating this via leaflets, public meetings and huge rallies.

The council explained that the slums were the real burden on the city, with high maintenance costs, low occupancy rates and low rental income; they were the cause of poor health and education outcomes as well as crime and social problems. The rental income on the new homes would pay for the loans, and the improved conditions would reduce costs on other services dealing with the social problems that arise in slum areas, and working-class people understood these arguments very well.

There were many public meetings, union meetings and rallies in the city, and our shop stewards called on union members to attend and make our voices heard. Many thousands of us responded to the call for action by joining mass rallies on a regular basis with up to 50,000 demonstrators; close to 10% of the population.

Liverpool District Labour Party meetings had an entirely different character to Labour Party meetings today. Meetings were hundreds-strong and included scores of delegates from the trade unions in workplaces from across the city, taking part in intense discussion and debate. It was this body, effectively acting at the height of the struggle as a city-wide workers’ parliament, which determined council policy. At no stage in the struggle were a majority of Labour councillors Militant members. Instead, workers and activists were politically convinced by Militant members putting forward a fighting programme and strategy.

Meetings were often very heated, with right wingers complaining they felt intimidated. A group of six right-wing Labour councillors broke the whip and wanted to give in to the Tories; they were labeled by the media as the ‘Sensible Six’. But their proposals were met with hostility in working-class communities where they were given a less flattering label with the same alliteration! These right-wing councillors complained about intimidation at public meetings and the media accused Militant of whipping up anger and aggression, but this was the natural reaction of working-class people unwilling to give in to Thatcher’s plan to place the city into ‘managed decline’!

‘Rate Capping Rebellion’

The ‘Rate Capping Rebellion’ at this stage had the potential to achieve a huge defeat on the Tory government. However, Thatcher had an important ally in this fight with support from Neil Kinnock, Labour Party leader. There were no elections in Liverpool in 1985, which was unfortunate as it would have shown support for the council’s campaign still growing.

At Labour Party conference that year, Kinnock lambasted the whole campaign; his treacherous speech revealed him to be a conscious agent of the ruling class and was a threat to other Labour councils not to join the rebellion. One by one, the other councils caved in, leaving Liverpool isolated. At the same conference, Kinnock, the son of a miner, who failed to adequately support their strike, also condemned the miner’s leader, Arthur Scargill.

In 1986, Kinnock followed up on his threats, orchestrating a witch-hunt of the left, expelling many leading Militant members. But in Liverpool that year, the vote for the Militant Labour council went up again and we continued to struggle. At the beginning of 1987, in the final stage of the appeal at the House of Lords, they ruled in favour of government auditors in a highly political decision. 47 democratically elected Labour councillors were removed and banned from office for five years. They were also surcharged, under laws that no longer apply today.

However, the Militant-led movement in Liverpool remained solid. Labour candidates were again elected on the same Militant programme, and again the vote for Labour in Liverpool went up! In reality, the courts weren’t Thatcher’s best weapon, that prize goes to the treacherous, undemocratic Labour Party leadership. In the general election of that year, Kinnock, having moved the party further to the right, led Labour to its third successive defeat. If the voting trend in Liverpool had been replicated nationally, Labour would have won a landslide.

None of the fighting Labour councillors were removed by Liverpool’s voters; they were removed undemocratically by Kinnock and Thatcher. Even after these attacks, Militant still had the organisation and authority within the movement to defeat Thatcher’s hated Poll Tax, with a nonpayment campaign which resulted in millions of people refusing to pay, and Thatcher was forced out of office. Kinnock continued the witch hunt and Labour lurched even further to the right. In 1992 he led Labour to a fourth successive defeat.

5,000 council homes

The lasting legacy of the Militant-led council is the 5,000 council houses that were built to replace the slums, they are now well-established estates among the most popular places to live in the city.

Also, there are the important lessons of the struggle; Margaret Thatcher couldn’t fight one union and one council at the same time; imagine if just a handful of Labour councils and unions had joined the struggle.

As for the fines of £350,000 faced by councillors – this money was raised by working-class supporters with a huge surplus of tens of thousands of pounds which was later donated to the Liverpool docks strike between 1995-98.

The Socialist Party stands strong today, fighting for the same Marxist programme and combative strategy, proven in Liverpool and in the anti-Poll Tax campaign. We continue to be the only party offering a clear and consistent programme capable of leading workers to a democratic socialist future.