Colonialism, national liberation and revolutionary struggle

Cédric Gérôme, CWI

Fifty years ago, in 1962, the ‘Algerian war’, one of the longest and bloodiest anti-colonial conflicts, ended with the victory of the Algerian fighters against French imperialism.

Algeria had been under French colonial rule for 132 years. It was the ‘flagship’ of the French colonial empire.

A policy of racial segregation and massive land dispossession was to the detriment of indigenous people.

The vast majority of Algerians were kept in crushing poverty and suffered systematic wage discrimination, which guaranteed huge profits for French big business.

At the outbreak of the conflict in 1954, one million European settlers -79% of them were born in Algeria – coexisted with nine million Algerians. There was also a large community of Jews.

At the top of the settlers’ ladder were the rich Colons, a tiny clique of people who wielded economic and political power.

The overwhelming majority of the settlers, however, were poor. By the 1950s, their average living standards were 20% lower than in France.

Following World War Two nationalist militancy and struggles rose steadily throughout the country, in the context of pro-independence struggles erupting internationally.

This coincided with unprecedented waves of workers’ strikes and an overwhelming desire for social change. In many cases, these disputes involved Algerian and French workers.

On 1 November 1954, the FLN launched a series of guerrilla-type attacks in different parts of the territory, targeting the bases of the colonial power. ‘Front de Liberation Nationale’ was a nationalist organisation composed of radical activists who, fed up with the growing conservatism and reformism of the traditional nationalist forces, had decided to ‘light the fuse’ of a general revolt against French rule.

The French army responded with systematic terror, involving burning down villages, creating makeshift concentration camps, summary executions and torture on a mass scale.

This violence exposed the brutal face of French capitalism – the so-called France of ‘human rights’.

Shockwaves

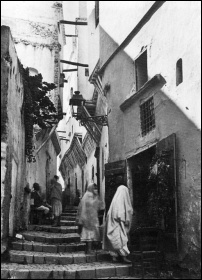

Algiers’ casbah, 1900, photo by Ed. Maurice Culot and Jean-Marie Thiveaud, Institut Français d’architecture (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

From the beginning of the colonial revolt, explosive labour disputes and waves of mutinies among conscript soldiers who refused to go and fight for ‘French Algeria’, affected dozens of French cities and towns.

As the war went on support for the colonial regime was declining at lightning speed. The financial consequences of the war began to create a budget deficit that spiralled out of control.

The unparalleled savagery deployed on Algerian soil by the authoritarian regime of Charles de Gaulle – who had taken power in France through a parliamentary coup in 1958 – could not end the war.

The offensive launched by the French troops in 1959 had almost finished the ALN, the armed wing of the FLN, as a fighting force.

But the heavy price, politically and socially, was directly affecting the French ruling class’s confidence and capacity to continue the war.

The mass pro-FLN demonstrations of December 1960, with the urban Algerian masses spontaneously pouring onto the streets in favour of independence, on a scale far exceeding what the FLN predicted, marked a turning point.

Moreover, in April 1961, the mass of French soldiers rebelled against an attempted coup by the generals.

De Gaulle had to struggle desperately to regain control of the army. In Blida (North), conscripts seized the main military base, arrested their officers and raised the red flag of revolution!

De Gaulle knew he had to act or risk losing control. By that time the issue had become one of managing an orderly retreat for French imperialism.

This is what ultimately happened with the signature of the ‘Evian agreements’ between the FLN and the French government in March 1962, opening the path to an independent Algeria.

The lack of a party advocating a programme for working class unity, in France but also, crucially, in Algeria was a key factor in channelling the anti-colonial struggle along nationalist lines.

The Algerian Communist Party increasingly lost public support as its leadership echoed French Communist Party – PCF – policy.

The FLN sought to take power by military force, with an army essentially based on the peasantry and the deprived urban population.

Significantly, the six FLN founders all came from a rural elite impoverished by colonialism; their world was rural Algeria and none of them had had any prolonged interaction with the working class movement.

Instead of orientating their efforts to build a common fight of all workers and poor, and of trying to split the European settlers on a class basis – including making guarantees to the European minority that their rights would be respected – most FLN leaders had a purely nationalist outlook, and had no programme to develop the country once independence was achieved.

Their methods included bombing public places frequented by working class and middle class European civilians.

Such actions contributed to divide Algerian and non-Algerian workers, and to push settlers en masse into the arms of pro-colonial reaction.

By the autumn of 1962, 99% of European settlers had left the country in fear of reprisals, one of the biggest population migrations of the 20th century.

No solution

Despite the courage and heroism of many pro-FLN fighters and supporters, their efforts did not lead to the changes they had hoped and fought for.

Following independence, the regime that took power in Algeria was a one-party state under the thumb of a mighty military machine.

This was a direct product of the military structures and methods adopted by the leaders of the FLN.

Indeed, the mass, democratic involvement of the working class – the only collective force capable of overthrowing capitalism and building socialism – was viewed by the emerging military bureaucracy of the FLN with suspicion and as a threat to its own power.

Balancing between capitalism and Stalinism, the Algerian regime was able to keep a “half way course” for a while, involving partial nationalisations that helped develop infrastructure, healthcare and education.

But as result of the fall of the Stalinist bloc, it moved further to the right and embraced mass privatisation and neoliberal counter-reforms that led to a profound disaster for the mass of the population.

Algeria today

Today, despite its rich oil reserves, most Algerians are blocked from any semblance of decent living conditions.

For the majority of Algerians, whose country is buffeted by poverty, corruption and violence, on the 50th anniversary of independence, there is hardly anything to celebrate.

The capital Algiers has been classified as among the least viable cities in the world. The notoriously retrograde ‘Family Code’ enshrines the status of women as minors for life.

Electoral contests are falsified, housing conditions are appalling, police abuses widespread.

The post-independence generation now constitutes the great majority of the population, and feels nothing but anger towards the corrupt elite in power.

In the light of the recent mass struggles that have engulfed the North African region, the time has come for this new generation to re-learn the lessons of the struggle for which about a million of their ancestors sacrificed their lives.

French left

The dominant view on the Algerian question within the ‘socialist’ SFIO (French section of the Second International) can be summed up through the words of a SFIO deputy who declared: “We want the men of Algeria to be more free, more fraternal, more equal, that is to say more French.”

One of the key points on which the Third, Communist, International, differentiated itself from the Second International was in its unconditional support for national liberation struggles against colonialism. But the Stalinist degeneration of Soviet Russia had shredded these principles.

While in the 1920s the French Communist Party (PCF) had taken a leading role in organising opposition to the Spanish-French Rif war in Morocco, by the 1950s this party had become a subservient appendage to the diplomacy of Stalinism, championing ‘national defence’, alliances with pro-capitalist forces and attempting to curb both workers’ and anti-colonial struggles.

Despite the pro-independence activism of many of its members and supporters, the PCF voted, in 1956, in support of the ‘special powers’ given to the government led by the ‘socialist’ Guy Mollet, intensifying repression in Algeria and sending hundreds of thousands of conscripts to the battlefield.

Background reading on the Algerian revolution

- Algeria: France’s Undeclared War, Martin Evans, £20

- A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-62, Alistair Horne, £11.99

- European Revolutionaries and Algerian Independence 1954-1962 edited by Ian Birchall for Revolutionary History. Vol. 10 No 4, £20

- National liberation, socialism and imperialism, V I Lenin, £6.95

Available from Socialist Books

Please add 10% postage, Cheques and orders payable to Socialist Books

PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD

Card payments 020 8988 8789