The struggle for a new mass workers’ party with a socialist programme

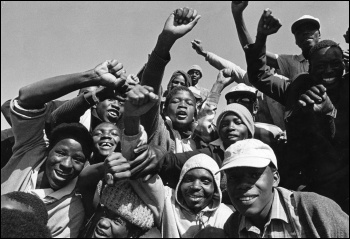

On 18 September, after six weeks of defiant strike action – when over 40 miners were killed by police acting on behalf of the mining bosses – Marikana platinum miners in Rustenburg, South Africa, won a significant 22% pay increase.

The Marikana strike action has spread throughout the mining industry provoking the anger of the bosses and African National Congress (ANC) government ministers alike.

On 5 October Anglo American Platinum fired 12,000 miners striking for better wages but with little hope of replacing these workers.

The strikes and the government response have also ignited a political volcano among South Africa’s working class with the demand for a new mass workers’ party finding an increasing echo.

In the following interview Democratic Socialist Movement (DSM) member Mametlwe Sebei – who is playing a leading role in the miners’ Strike Coordinating Committee – explains the political tasks facing the workers’ movement.

The DSM is an affiliate of the Committee for a Workers’ International – CWI – to which the Socialist Party is also affiliated.

Extracts from an article on the Daily Maverick, a South African online news site, 4 October, by Mandy De Waal.

The industrial action isn’t only about better wages, says Mametlwe Sebei, a leader in SA’s Democratic Socialist Movement, which is helping to coordinate independent strike committees in Rustenburg and beyond.

“We are campaigning for a new party, for a labour or socialist party to emerge,” says Sebei, who added that the Democratic Socialist Movement was mandated to draw up a resolution that can be voted on by mine workers to make a case for a party.

The paper, which has not yet been circulated amongst workers, would also highlight the programme and ideology of what would be a new socialist, labour party.

“This is not an idea that emerged from us at the Democratic Socialist Movement, but in actual fact it has emerged on the ground,” says Sebei. “That is not to say that we haven’t been consciously campaigning for this, but the circumstances and conditions in Rustenburg have rapidly changed consciousness.

“What the workers are asking is: ‘What are we doing about this government that is killing us?’ The ANC has never represented the working class, and even though this country has been built on the blood of mining workers, neither does Cosatu [the main trade union federation].”

“The illegal strikes show that the NUM [National Union of Mineworkers – the largest affiliate of Cosatu] has consciously acted against the mandate it has been given by the workers, and if anything they are the conscious agents of the mining bosses.

“NUM through Cosatu is knotted into the tripartite alliance that of and by itself ties itself to the interests of the mining bosses who are represented by the ANC.”

A case in point, believes Sebei, is the sponsorship of Cosatu by Patrice Motsepe, who ranks as the fourth wealthiest man in South Africa with a net worth of some R22.75 billion [£1.6 billion] as at March 2012, according to Forbes.

Motsepe has interests in platinum, gold, coal, iron and manganese through African Rainbow Minerals, the company that helped build his billions, and was one of the first big Black Economic Empowerment winners post democracy, when mining rights were only granted to ’empowered’ companies.

In its profile, Forbes talks about how Motsepe is labelled as an ‘oligarch’ in this country.

“Motsepe has been sponsoring Cosatu for years. If you look at the report for the congress before this one, Motsepe was the biggest donor. This means that Cosatu is highly compromised,” says Sebei.

“A debate has emerged about whether it is time to reconstitute the labour movement,” says Sebei. “This is a debate that is emerging within our own ranks, but the events of Rustenburg and the workers’ own action in defiance of mine bosses and NUM show that the move to earnestly rebuild the labour movement from scratch has begun.

“The workers will reclaim the labour movement for their own control and their own struggle, and I think that is a warning to Cosatu and to the rest of the other unions in Cosatu who think that they have a God-given right to lead the workers.”

Sebei said that the Democratic Socialist Movement was campaigning for a new socialist, labour party to emerge. “We need to be able to build a mass political party that will unite all the workers in the mining industry with all other workers in all other industries, but also with all communities in struggle, and with youth in campuses… this is an idea that has found its echo in Rustenburg and beyond.”

The call for a mass political alternative, which Sebei said would be based on the ideas and programme of socialism, would be given a loud voice on 13 October 2012 when workers, activists and youth march from Church Square in Pretoria to the Union Buildings.

“We are saying that the entire mining industry, and the rest of the economy, must be brought under democratic control and management of the working class.

“This means that mines must be nationalised first and foremost, so that the economy can be planned to meet the needs of the people, and not for the profits of those who have become rich at the expense of all of us during the past 18 years of democracy,” Sebei says.

“The working class needs a political party and government of their own, one that will take the entire economy under democratic control to ensure that our sweat and blood is not for the few, and to ensure that the misery we are wallowing in isn’t a natural order of things.

“Our country is enormously wealthy – wealthy enough to create a better life for those living in misery, poverty and unemployment.

“All the parties that exist currently are different shades of capitalism. There is no one party that represents the interests of the working class.

If you look at the number of people who are qualified to vote and who don’t vote, it is not because of a lack of political interest, it is because no one represents the workers. There is no one to take our issues to government,” he says.

Sebei says that the first matter to attend to should be the strikes, and anticipates it is likely that the new labour-driven political party will be launched next year.

- DSM members are travelling thousands of kilometres every week across the Rustenburg region and beyond, helping to coordinate the action of the striking miners. The DSM is appealing to members and supporters of the CWI to help finance this activity.

- Make donations payable to Socialist Party and send to ‘South Africa Appeal’, PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD. Online: Put ‘South Africa Appeal’ in the message box – www.socialistparty.org.uk/donate

“The mineworkers’ rejection of their traditional negotiators has allowed rivals such as AMCU and the Committee for a Workers International, a communist group, to recruit platinum miners and lead the strikes.” Sunday Tribune, South Africa

SOCIALISM 2O12

A South African miners’ leader and Democratic Socialist Movement member from Rustenburg, South Africa, will be speaking at Socialism 2012 on 3rd & 4th November in London on the miners’ general strike and the political tasks facing the South African working class. http://www.socialistparty.org.uk/events/Socialism_2012

Black History Month

From apartheid to Marikana – the struggle for social justice continues

April Ashley Socialist Party and black members’ rep on Unison national executive (personal capacity)

The victorious strike of the Marikana mineworkers has transformed the situation in South Africa and heralded an upturn in workers’ struggle.

The strike has spread like wildfire to other mines and enormously boosted the confidence of workers in South Africa. It has ignited a new stage in the South African revolutionary movement.

The massacre of over 40 mineworkers in “scenes reminiscent of the worst of the apartheid era massacres” (Business Day 17/08/2012) shocked to the core South African society, catapulted South Africa to the forefront of international workers’ struggles and enlisted the solidarity and support of workers worldwide.

The struggle has brought back memories of the fight against apartheid for older workers and an interest in the struggle for young people.

It was in 1994 that the black majority population finally secured one person, one vote and ended apartheid with the election of the first black African National Congress (ANC) government, under a negotiated settlement.

The whole world held its breath on 11 February 1990 – that historic day when Nelson Mandela was released from prison after 27 years.

The hopes and dreams of the majority for a new South Africa rested on his shoulders: a new South Africa freed from ferocious and pitiless oppression and exploitation by white minority rule.

His release was secured after decades of bitter struggles when the apartheid regime attempted to drown the revolution in blood.

The Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and the heroic Soweto uprising of the youth in 1976, when up to 100 young people were shot dead by police, (see article, right) showed the determination of the masses to overthrow apartheid.

The adoption of the Freedom Charter by the ANC in 1955 was an expression of workers’ demand for a revolutionary change in society.

The charter called for the nationalisation of the commanding heights of the economy: “The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people, the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole.”

Workers’ struggles

Between 1961 and 1974 the number of black workers employed in South Africa’s manufacturing industry doubled.

It was the explosion of the organised working class onto the scene, carrying on the banner of the dockworkers’ strikes in 1973, that rocked the whole of South Africa and brought a qualitative change to the struggle.

These mass strikes fired the imagination of workers internationally who gave solidarity to the struggles through marches, lobbies and boycotts and lead to many workers becoming politically active as they supported their brothers and sisters in South Africa.

The 1980s workers’ movements lead to the birth of the Confederation of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) in 1985.

Cosatu adopted the Freedom Charter in 1987 under the banner ‘Socialism means Freedom’. Its largest affiliate, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), led by the then militant Cyril Ramaphosa, was at the forefront of mass strikes, and Cosatu began a series of general strikes which made the country ungovernable and ushered in the end of apartheid.

But 20 years after the end of apartheid what has happened to the hopes and dreams of the workers encapsulated in the Freedom Charter?

The Socialist Party and the CWI have explained that following the collapse of Stalinism the white regime of FW de Klerk recognised the potential for a power-sharing agreement with the ANC.

The fundamental economic interests of capitalism would not be threatened because of the ANC leadership’s shift to the right, betraying the revolutionary struggle.

Failure of ANC

South Africa is now the most unequal country in the world with the wealthiest 10% of the population taking 60% of its total income while the bottom half of the population earns less than 8%.

Almost one quarter of South African households experience hunger on a daily basis. An average worker lives on R18 (£1.30) a day but 44% of workers – six million workers – live on less than R10 a day. Unemployment is 25% with 50% youth unemployment.

This means workers continue to live in crushing poverty. “A mineworker outlined his working and living conditions: ‘We spend eight hours underground.

“It’s very hot and you can’t see daylight. There is no air sometimes and you have to get air from the pipes down there.’ His shack has no electricity, no running water, and the outside toilet is shared with two other families” (the Guardian 7/9/12).

Apart from the short-lived reconstruction and development programme in their early years in government, which saw limited improvements for the black working class, the ANC has pursued an aggressive neoliberal economic programme with mass privatisations of public utilities like electricity and water which has led to the increased pauperisation of the working class.

This has fuelled a myriad of community struggles for housing and delivery of services for many years.

For example, the ending of subsidised water supply in Kwa Zulu Natal in 2000 lead to the biggest cholera epidemic in the country’s history as workers went to the dams and rivers to drink as they couldn’t afford to be reconnected to the new more expensive supply.

Mass public sector strikes against privatisation in 2007 and 2010 shook the ANC government which has been ruling in a tripartite alliance together with Cosatu and the South African Communist Party (SACP).

Divisions have widened in the alliance as the ANC effectively abandoned the working class and became conscious agents of the big bosses and capitalism.

Some Cosatu leaders have also been assimilated into the ranks of the elite and have abandoned the struggle.

Cyril Ramaphosa was paid £61,000 as a Lonmin non-executive director last year and has come to symbolise the gap between a new black elite and the poverty-stricken majority.

Socialist alternative

Following the Marikana massacre the credibility of the ANC has now been shattered. It has demonstrated that it shares with the capitalist class the same fear and loathing for the working class.

“The ANC was in the black mind, the black soul, it took on an almost mystical quality. But now they’ve lost faith in it. The bond is shattered and it happened on television” (the Guardian 7/9/12).

As the global economic recession deepens the bosses, backed by the ANC government, will continue their attempt to load the burden onto workers’ shoulders.

So the scene is set for not only continued explosive struggles but a split in the tripartite alliance and the ANC itself.

The Democratic Socialist Movement (the CWI section in South Africa) are proposing a Rustenburg general strike, to be followed by a national strike and demonstration.

International pressure by workers and activists must also be maximised. The enthusiastic response to the ideas of the DSM among workers indicates the great potential for the development of a new mass workers’ party with a socialist programme, to defend and further the interests of working class people in South Africa.

For London Socialist Party meetings to mark Black History Month, see:

____________________________________________

Soweto uprising 1976

In 1976 South Africa’s vicious apartheid regime was shaken by a heroic uprising started by thousands of school students in the black ‘township’ of Soweto near Johannesburg.

The police killed at least 140 people on 16-17 June 1976, mostly in Soweto, and 600 more as they tried to put down the year-long revolt.

South Africa was then still under the apartheid regime which used ‘separate development’ to disenfranchise, racially segregate and keep down the country’s black majority and to ensure plentiful cheap labour.

The ruling Nationalist government insisted that school lessons in certain subjects must be taken in Afrikaans – associated with white minority rule and particularly with the oppression of apartheid.

Students had begun boycotting Afrikaans classes and elected an action committee that later became the Soweto Students’ Representative Council (SSRC). The campaign started with a demonstration on 16 June.

The police fired tear gas into the crowd, estimated at 12,000 strong. The students replied with a volley of stones.

The police then fired directly into the crowd. 13-year-old Hector Petersen was one of the first victims, being shot down in front of his sister and friends.

The education system was the spark but there were many such grievances throughout apartheid South Africa, especially in the townships.

Militant (the Socialist’s predecessor) described Soweto as a “powder keg waiting for a match to set it alight” with “virtual concentration camps”.

“A million Africans are packed into Soweto. Half the population is unemployed and therefore without permits to stay, at the mercy of any police raid.”

The article contrasted the dreadful conditions of the townships with the privileged life of many middle class whites.

The Soweto uprising changed the political consciousness of South Africa’s black working class.

Youth in Alexandria township, north of Johannesburg, had seen that they couldn’t beat the apartheid state forces by themselves and appealed to their parents at work to back them.

By 22 June 1976, over 1,000 workers at the Chrysler car factory had stopped work in the first strike action consciously held in support of the students.

In Soweto, the SSRC took on the responsibility of organising for a student march into Johannesburg on 4 August and, for three days, the first political general strike since 1961 took place.

The government conceded on the Afrikaans issue but the revolt had gone too far and was now clearly aimed at the regime itself.

Roger Shrives

________________________________

South Africa – From slavery to the smashing of apartheid by Peter Taaffe

£1.25 including postage

Available from Left Books , PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD. 020 8988 8789 [email protected] www.leftbooks.co.uk