Black History Month

Who was Malcolm X?

Hugo Pierre, Tower Hamlets Socialist Party

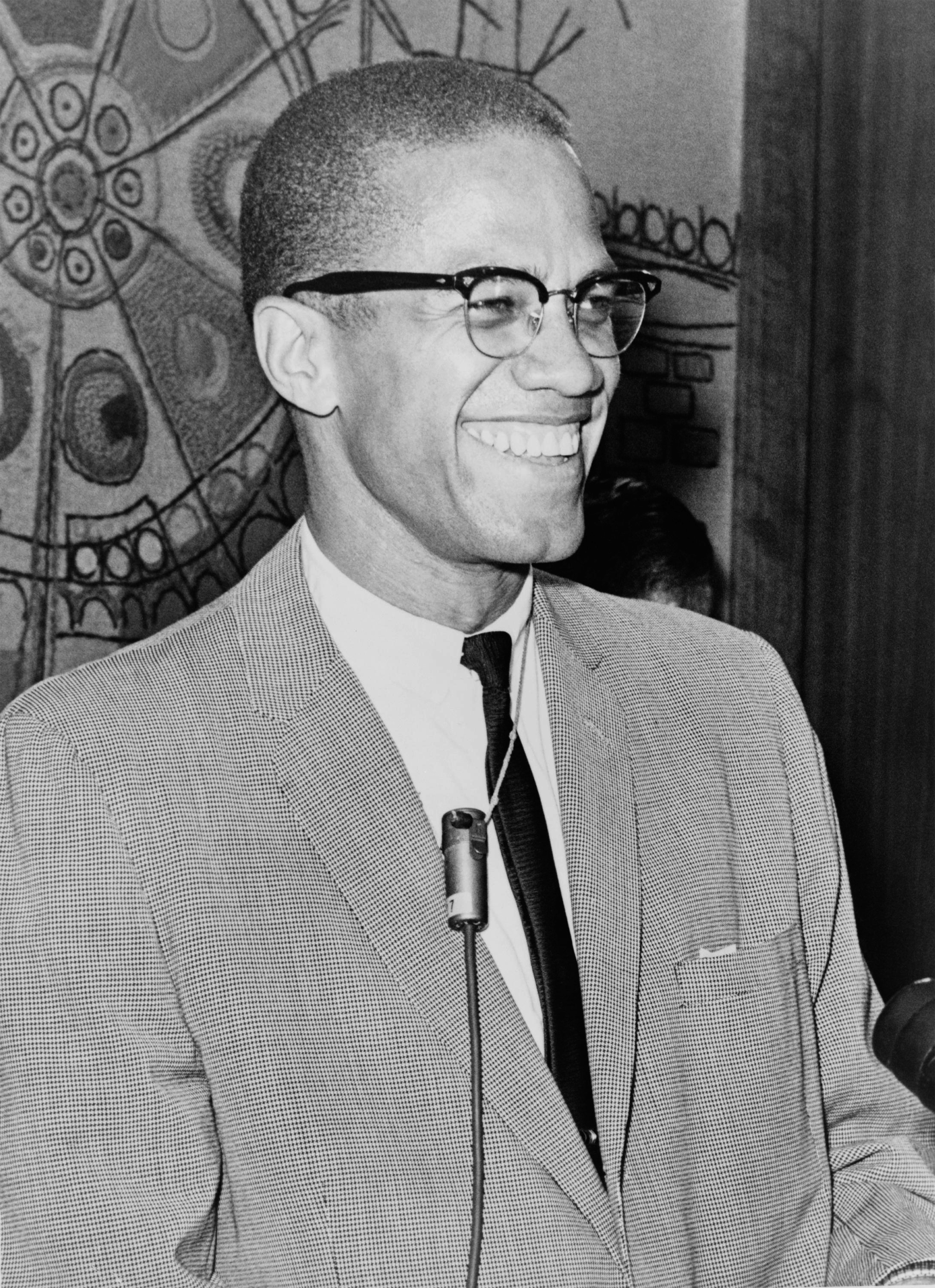

Malcolm X, 12 March 1964, photo Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection, Ed Ford, World Telegram staff photographer (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

“By any means necessary” – Malcolm X’s expression of militant civil rights – is known worldwide by young people fighting against racism.

In the 1950s and 60s, black workers in the US southern states rose up to end their status as second-class citizens, segregation and the vicious enforcement of the vile, racist Jim Crow code.

The struggles of black workers in the 1940s, including winning equal pay in some of the war industries, was allied to the experiences of those who fought during World War Two.

Encouraged to fight for US capitalism under the banner of ‘freedom’ they returned to find their rights, even to a seat on a bus, severely restricted at home.

Bus company boycotts sprang up in many southern towns and cities, which eventually ended segregated buses in Montgomery.

These struggles, organised by black workers and trade unionists, forced many elements of the black ‘establishment’ into action – particularly the churches.

A new leadership, particularly around Martin Luther King Junior, based their method of struggle around the principles of non-violent action.

The mass struggle that developed engulfed the south and inspired black workers and youth throughout the north.

The political establishment, both Republican and Democrat, feared the potential for this movement and tried to entangle the leaders with promises of reform in the future.

Poverty

Malcolm X came to the struggle from a life of poverty as a teenager, petty crime and prison, via the Nation of Islam.

The Nation condemned the objectives of the civil rights movement leaders for integration into US society, posing instead the fight for black separation with a message that whites were ‘devils’.

Prior to Malcolm joining, the nation was a small sect. Malcolm’s skills and enthusiasm, against the backdrop of racism, poverty and police brutality, led to a huge rise in membership across northern states.

While segregation didn’t legally exist in northern states, poverty and discrimination – including police brutality – left the majority of blacks in the worst housing, worst jobs and worst conditions.

Malcolm organised a mass protest against the savage beating of a Nation member in Harlem by the NYPD.

The police were forced to release the Nation member into hospital for treatment. Thousands applied to join the Nation overnight.

The Nation made radical speeches but over time Malcolm became uneasy with their lack of action. Southern mass movements were challenging the power of the state.

Boycotts, mass demonstrations and campaigns for voter registration were met with brutal resistance, including police murders and racist thugs such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Youth were starting to turn away from non-violence and attempting to work out a programme to defeat state violence.

Conflict

Malcolm came into conflict with the Nation’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, when he wanted to organise violent reprisals following the LAPD’s murder of a Mosque leader in 1962.

Malcolm was ordered to ‘stay where I put you’ and not organise a united front campaign with civil rights campaigns.

Malcolm was increasingly involved in organising protests and pickets, supporting workers’ struggles in New York, talking less about religion and more about the social questions facing blacks.

The Nation ordered its members not to participate in the 1963 March on Washington, organised by a coalition of civil rights groups.

Hundreds of Nation members defied this edict. Malcolm, while not openly defying it, participated in the lead up and watched the march.

But Malcolm then denounced the march leaders, who relied on possible civil rights legislation, for making the demo a “Farce on Washington”.

Black youths, along with Malcolm X, were angry that there was no call for more mass action, in particular strike action.

Malcolm’s idea of revolution still came within the framework of black nationalism. But within months he was expelled from the Nation, which by now had millions of dollars invested in real estate and black businesses.

Malcolm’s trips to Mecca broke his view that ‘the white man is a devil’ and brought him into contact with leaders of the colonial revolution in many African states. Malcolm noticed that many of these leaders embraced ‘socialist’ ideas.

On returning to the US he made clear that he was not anti-white, but anti-exploitation and anti-oppression. He called for black armed self-defence.

Racism and capitalism

Malcolm was drawing conclusions about the nature of capitalism and the integral role racism played within it.

His support for workers’ struggles, alliances with black groups combined with links to the white working class posed a serious threat to the state. He was murdered by the state, with the collusion of the Nation, on 21 February 1965.

But a new generation of black youth reached the conclusion that armed self-defence and a socialist programme were essential to the struggle for black liberation.

The Black Panthers’ ten-point programme, written in October 1966, included demands for housing, employment and education but also “placing the means of production… in the community”.

‘Legal rights’ against discrimination have not ended economic segregation and state harassment through police brutality.

A black US president, Barack Obama, has presided over the worst fall in living conditions for black workers since the 1930s.

The struggles of the working class, such as those in Wisconsin, and the Occupy Movement, will enthuse a new layer of black youth to look at the life and methods of Malcolm X, especially the anti-capitalist conclusions he drew towards the end of his life.

Only a new society, based on public ownership of the huge wealth and resources and democratic planning, can lay the basis for the eradication of racism once and for all.