A revolt against imperial power and war

Cillian Gillespie, Socialist Party (CWI Ireland)

This year marks the centenary of the Easter 1916 Rising against British rule in Ireland. For many working class people in Ireland this event is regarded as a key defining event in Irish history, with its participants and leaders held in high esteem.

Their actions are viewed by many as a blow to Ireland’s historic colonial masters. Over the course of one week, a small armed force took on the military might of the British Empire, which at the time constituted the largest imperial power in the world.

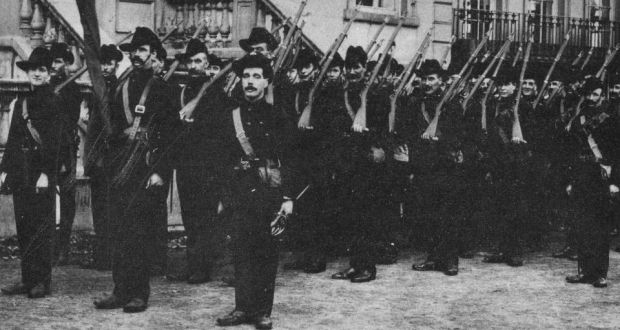

A significant proportion of the main forces that participated, the Irish Citizen Army and the Irish Volunteers, were working class in their composition or were drawn from the lower middle classes.

While the capitalist establishment in the South is more than willing to celebrate the rising in this centenary year, their forebears took an altogether different attitude to the events of 1916.

James Connolly

Nowhere is this more exemplified than in an editorial that appeared in the Irish Independent on 10 May 1916, with a picture of the great socialist leader and key participant in the rising, James Connolly, beside it, which demanded that “the worst of the ringleaders be singled out and dealt with as they deserve.”

A badly wounded Connolly was executed two days later. The paper’s proprietor, William Martin Murphy, leader of the 404 bosses that had locked out Dublin’s working class in 1913, was effectively campaigning for his execution.

Ultimately the rising had its roots in the oppression by British imperialism that had stretched over several centuries. This colonial oppression of Ireland had not only resulted in the denial of its right to political freedom and independence, but also its economic strangulation.

This was firstly done by destroying Ireland as a competitor to British capitalism in the aftermath of the Act of Union of 1801.

Mass emigration from Ireland, particularly in the years of the great famine of the mid-19th century, also served to create a cheap pool of labour for Britain’s industrial cities and “dark satanic mills”.

Social struggle

Ireland became Britain’s ‘bread basket’ and would provide raw agricultural products, mainly meat, to feed these same cities.

It was for this reason that James Connolly wrote: “The struggle for Irish Freedom has two aspects: it is national and it is social.”

Connolly argued that only a revolutionary movement of the working class that united both Protestant and Catholic workers, and linked with the struggle for socialism, could end Ireland’s colonial domination.

Alongside Jim Larkin, Connolly played a critical role in the huge battles of the Irish workers’ movement in the aftermath of the founding of the Irish Transport and General Workers Union in 1909. This culminated in the Dublin Lockout of September 1913.

While not an outright defeat, the outcome of the lockout did cut across the momentum that the ITGWU and Irish workers’ movement generally had developed prior to 1914. Two other events were to have a negative impact on the development of the workers’ movement in this same year.

The first was the danger of the partition of the island. Connolly correctly foresaw that this would produce a “carnival of reaction”. Such a scenario, as history would later prove, would result in the increase in sectarian division between working class people to the benefit of imperialism and capitalism.

In August 1914 another catastrophe befell the workers’ and socialist movement in Ireland and throughout Europe, with the outbreak of World War One. This was a war fought between the capitalist powers of Europe over whose respective ruling class would maximise their profits through control over the world market.

This event may not have come as a surprise to socialists such as Connolly, but the support given to it by the ‘official’ leaders of the socialist movement certainly did (see ‘1914 – The capitulation of the Second International’ at www.socialistworld.net).

In violation of the basic principles of working class solidarity, they shamefully rallied in support of their own ruling classes in a war that would result in the killing and maiming of millions of working class soldiers, unprecedented in its barbarity.

Europe

As Connolly wrote in 1914, following the betrayal of the leaders of the socialist Second International: “What then becomes of all our resolutions; all our protests of fraternisation; all our threats of general strikes; all our carefully built machinery of internationalism; all our hopes for the future?”

Irish Home Rule leader John Redmond – who the present southern Irish caretaker government saw fit to recently celebrate on a large scale banner in Dublin’s College Green (see photo right) – rushed to support the imperialist war and advocate that members of the Irish Volunteers should enlist in the British army.

In contrast, Connolly wrote in hope that: “Ireland may yet set the torch to a European conflagration that will not burn out until the last throne and the last capitalist bond and debenture will be shrivelled on the funeral pyre of the last warlord.”

As the bloody carnage of the war dragged on, Connolly was driven by a burning desire to strike a blow against the capitalist and imperialist order in Europe.

However, he was isolated in Ireland, with no direct links to the small number of other revolutionary socialist leaders who stood against the imperialist war, such as Lenin and Trotsky in Russia, Luxemburg and Liebknecht in Germany, and Maclean in Scotland.

During the war, Ireland was not immune from the jingoism that had developed across Europe. Many working class people in Ireland, including those who had been blacklisted as a result of the lockout, were also economically conscripted into the British Army. Linked with this was the looming threat of actual military conscription being introduced in Ireland, as it had been in Britain.

It was in this context that Connolly became increasingly desperate to see some kind of rebellion take place in Ireland. In the absence, at that stage, of a mood for rebellion among broader sections of the working class, he looked to the forces of militant nationalism.

These forces took the form of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and those sections of the Irish Volunteers who had refused to heed Redmond’s call to support the British military effort.

Easter Monday

The IRB’s maxim was: “England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity”. It had been preparing in secret for an armed rising since the outbreak of the war. In January 1916, Connolly was co-opted onto the military council of the IRB to prepare for a rising to take place at Easter.

On Easter Monday (24 April) 1916, an estimated 1,300 Irish Volunteers and 220 members of the Irish Citizen Army (Connolly’s trade union militia) seized control of the centre of Dublin. They declared an ‘Irish Republic’, erected barricades and waited for the inevitable assault from British forces.

For one week, the insurgents stood firm even though outnumbered by 20 to one. They were quickly surrounded and shelled mercilessly.

By the end of the week they were forced into an unconditional surrender. 60 rebels, 120 British troops and 450 civilians lay dead, with more than 2,500 injured.

Various factors cut across the scale, duration and intensity of the fighting that took place. The countermanding order to the Irish Volunteers by McNeill – the nominal head of the force – who reflected the conservatism of the Irish middle classes – on Easter Sunday was one. Also the British seizure of the German submarine, the Aud, which contained 20,000 rifles set for the rebels.

However, ultimately the rising was doomed to failure from the outset, given that there was little mood or support for such an action among the population at large.

No attempt was made to organise a general strike in support of the uprising and no class appeal was made to the British troops sent to put down the rebellion.

Connolly himself confided to a fellow insurrectionary that there was no chance of the uprising succeeding.

In the run up to and during the rising itself, Connolly made political concessions to the forces of nationalism he was fighting alongside, setting aside some of the ideas and methods he had so carefully developed during decades of revolutionary activity.

This was reflected in the ‘Proclamation’ he put his name to, which, notwithstanding its positive sentiments, is a nationalist document.

Having decided to participate in the rising, it would have been better if Connolly had put out a clear, separate, socialist document that outlined his vision of a “Workers’ Republic”, where society’s wealth and resources would be under the democratic ownership and control of the working class.

Revolution

The tremendous courage and self-sacrifice displayed by Connolly, and indeed the others who fought in the rising, cannot be disputed. However, the prematurity of the rising can be seen by looking at events that followed it.

In the opening chapter of his celebrated work ‘Labour in Irish History’, Connolly had written that: “Revolutions are never the by-products of our minds but of ripe material conditions”.

While the “material conditions” for a socialist revolution against British and Irish capitalism had not developed by 1916, the impact of national and international events in the period following 1917 made such a revolution a real possibility.

The outbreak of the Russian Revolution and the revolutionary wave that swept Europe had a deeply radicalising effect on the working class on the island.

This radicalisation had an effect not only on the South, where opposition to British imperialism began to harden in the aftermath of the rising, but also among Protestant and Catholic workers in the North. This resulted in a whole series of local and national general strikes. “Soviets” – democratic workers’ councils – were proclaimed. And, in some cases, strikers and workers took control of cities, such as Belfast and Limerick. A pro-socialist outlook developed within society.

Socialism

The absence of a revolutionary socialist leadership, which could have united the working class and these movements in the struggle for socialist change, meant that the revolution of this period gave way to the counterrevolution of the partition of the island.

Tragically, Connolly did not live to see these events and therefore play the necessary role in building such a leadership.

Contrary to the mythology purported by today’s political establishment and mainstream historians, the “revolutionary period” of 1916 to 1922 did not give way to a positive outcome for working class people. What was created were two oppressive, sectarian states that failed to deliver for the needs of working class people, and still do to this day.

It is for these reasons that we must learn from the past, and strive to construct a socialist movement that can deliver the real change that working class people need.