Non-fiction review: Petticoat Heroes

Uncovering the class struggle behind the Rebecca Riots

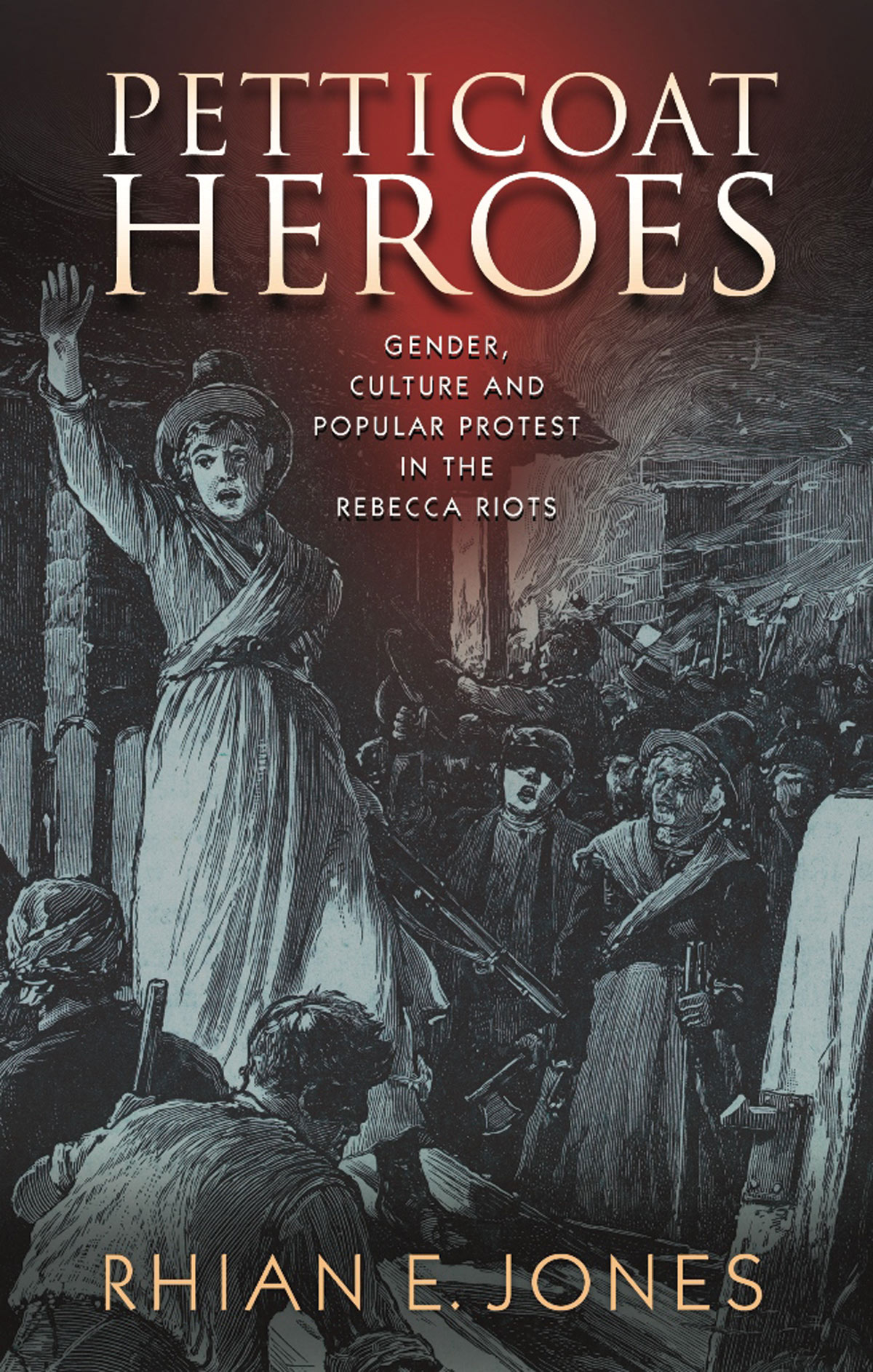

‘Petticoat Heroes’ by Rhian E Jones examines the working class protest movement which most historians dismiss as simply the ‘Rebecca riots’ (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

Scott Jones

Every kid growing up in Wales knows the story of the Rebecca rioters. Men who dressed as women in the ‘olden days’, rampaging through the land smashing up toll gates.

The Rebecca Riots, which mainly took place in south-west Wales in the 19th century, occupy an important place in Welsh history. One of the exhibits at the museum of Welsh life in St Fagans is a surviving toll gate. Despite this, general understanding rarely moves beyond the above description – partly because so little has been written on the subject.

That’s why ‘Petticoat Heroes’ by Welsh writer Rhian E Jones is so welcome. Rhian’s book is not only a modern, class analysis of the Rebecca Riots – but also looks at the subjects of gender and culture in relation to the riots for the first time, providing fascinating interpretations alongside meticulous research.

Rhian from the outset makes a case for the riots to be understood as a broader movement which she calls ‘Rebeccaism’. The riots weren’t only against the imposition of toll roads – which they beat. And they weren’t only riots. They were a general protest movement “against high rents, tithes, evictions, workhouses and the New Poor Law.”

This is a very important point. The age was one of mass struggle. The year the riots started, 1839, was the same year as the Newport Rising. 7,500 working class men from the Welsh Valleys, led by Chartists – probably the world’s first mass working class movement – stormed Newport to free imprisoned comrades and attempt to seize power.

While traditional accounts mainly portray the Rebeccaites as farmers in rural west Wales, many were workers. There were clear attempts to link up with the more proletarian Chartists further east, which terrified the ruling class. Rhian points out that the country’s first Chartist branch was actually founded in Carmarthen, the heart of Rebeccaite territory.

The linking up of the two movements also worried the better-off Rebeccaite farmers and landlords. They put forward their own, more conservative class demands through Rebeccaism, and colluded with authorities to sell out more militant Rebeccaites.

One such militant was John Jones, known as ‘Shoni Sguborfawr’ – Johnny Big Barn. He was a notorious ‘troublemaker’ turned Rebecca rioter, a product of working class Merthyr, who was arrested in a pub in Tumble, south-west Wales, after a tip-off by more conservative Rebeccaites.

This revolutionary undercurrent was understood by the press at the time, as Rhian reminds us. The Carmarthen Journal viewed Rebecca as “personifying a troubling ‘spirit of political disaffection'”, asking the question ‘who is Rebecca?’ The paper answers: “an embodiment of the principles of revolution.”

In popular culture too, Dylan Thomas’s take on the riots, ‘Rebecca’s Daughters’, is a comedy with a serious message: governments only bring in serious reforms when they are afraid of a revolution.

The other core theme of ‘Petticoat Heroes’ is gender. Rhian concludes that “Rebeccaite cross-dressing demonstrates that the movement’s use of costume was more complex than previously recognised”.

Viewing the protesters as ‘men dressed as women’ is too simplistic. Especially given that, as well as opposition to toll gates, they opposed the sexist attacks of 1834’s New Poor Law – “most visibly through insisting upon the right of unmarried mothers to public support.”

Intriguingly, Rhian also writes that the Rebeccaites’ costumes made dressing like women a fashionable or cool thing for men to do. That’s a far cry from the official image of Victorian Britain as stuffy and conservative.

Ending by connecting the role of Rebeccaite imagery and disguise to contemporary protest movements like Occupy’s use of Guy Fawkes masks, ‘Petticoat Heroes’ is fantastic for the breadth of issues it covers on a phenomenon most accounts present as a mere quirk of history.

It also connects Rebeccaism to the all-important class struggle taking place at the time, and its lessons for today. And as the reader makes these discoveries, Petticoat Heroes is an enjoyable read too.

- ‘Petticoat Heroes’ – available soon from www.leftbooks.co.uk