by Peter Taaffe, to be published in the November issue of Socialism Today

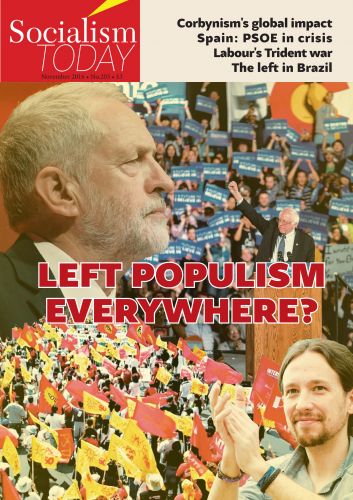

Marxists from Spain and Britain met recently in London to discuss the dynamic developments taking place in the world today. At that meeting from 20 to 22 September, representatives from El Militante/Izquierda Revolucionaria, the Socialist Party and the Committee for a Workers’ International agreed to an exchange of material to be published in their respective magazines and journals. This is the second of the articles from that initiative, by Peter Taaffe, Socialist Party general secretary, who puts the Corbyn movement in the context of an international wave of left-wing populism.

An article by Juan Ignacio Ramos, Izquierda Revolucionaria general secretary, explaining how the recent dramatic crisis in Spanish social democracy is being driven by class struggle, was posted on 17 October on the CWI website; click here to go to it.

Jeremy Corbyn, through mass support, has fought off the attempted coup by right-wing Blairite Labour MPs and their supporters. Corbyn actually increased his majority in the second Labour leadership campaign in twelve months. But the Labour right and behind them the strategists of British capitalism still remain unreconciled to his victory, so the ‘civil war’ that has raged throughout the party since his initial election will continue unabated. The main reason for this is to be found in the determination of the pro-capitalist Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) and its supporters, backed up by the venal capitalist media, to continue their campaign, not even excluding a third attempt to unseat Corbyn.

And, if they again fail, they hope that a snap general election will do the job for them. They expect the Tories to win an election and, as a consequence, Corbyn will be removed. In this sense they are ‘counter-revolutionary defeatists’. However, in the explosive social situation of Britain, together with disarray in Tory ranks over Europe and other issues, it is possible that a Corbyn-led Labour Party could win an election!

But how did Jeremy Corbyn use his colossal victory at the Labour Party conference in September? He and his main ally, shadow chancellor John McDonnell – along with their supporters in the Momentum group – attempted to offer the right a way back. This has been the pattern throughout Labour history. On those rare occasions when the reformist left have won, they invariably failed to capitalise on their victory. When the right are in the ascendancy, they go all out to isolate and crush the left, as happened in the purges and expulsions of the 1980s, first against Militant and then the rest of the left, including the supporters of the late Tony Benn.

Corbyn risks repeating this pattern by including the defeated right in his shadow cabinet. Meanwhile, a majority of the new leftward-moving Labour Party workers wish to deselect the Blairite MPs and their ideological bedfellows who represent a capitalist Trojan horse within the party. But, as the Socialist Party (formerly Militant) has consistently pointed out, weakness invites aggression.

The right did not even wait until the conference had finished. The deputy leader of the Labour Party, Tom Watson, used his conference speech to attack Jeremy Corbyn. Egged on by the capitalist media, he sought to prepare the ground for a right-wing comeback by demanding a return to the previous system of electing the shadow cabinet, which would put power back into the hands of the PLP and cut Corbyn and the left’s powers, while disenfranchising ordinary members.

A few weeks prior to the conference, Watson had also attacked so-called ‘Trotskyist entryists’ – particularly members of the Socialist Party – who were allegedly joining Labour and using ‘arm-twisting’ methods to win over the more than 600,000 Labour members, particularly young people! Jeremy Corbyn publicly dismissed this as nonsense. In the 1980s, he had supported a parliamentary motion calling on the Russian government to rehabilitate Leon Trotsky.

We answered Watson’s narrative of a ‘sinister plot’ of ‘secretive’ Trotskyists seeking to penetrate the party. We openly declared our willingness to join, if we were allowed the same rights as, for instance, the Co-operative Party, which has been affiliated to the Labour Party since 1927. This reflected the original open, federal character of the Labour Party when it was formed. Socialists, Marxists, the trade unions – which provided the mass spine of the party – debated and discussed with each other on how to build the party into an effective weapon against capitalism within a loose but effective federation.

This form of organisation is quite common among European workers today – particularly in Greece, Spain, Portugal, etc. In Britain, this was effectively destroyed by the rise of the Labour right, particularly in the 1920s. They moved to a more centralised bureaucratic form of organisation, beginning with the exclusion and expulsion of Communist Party members.

We used this attack to familiarise a wider audience of workers and youth with the real ideas of Leon Trotsky: workers’ democracy, internationalism and socialism. Moreover, we demanded that all those who had been expelled in the 1980s and since be reinstated. This included the Militant editorial board and our heroic Liverpool city council comrades, whose only ‘crime’ was that they and many others stood up successfully in defence of the working class. We reminded the labour movement that it was Militant and the Liverpool 47 councillors who defeated Margaret Thatcher and forced her to give significant concessions to Liverpool. It was also us, not the Labour leadership, who organised and led the anti-poll tax struggle which again defeated Thatcher. This movement mobilised 18 million people not to pay the tax and in the process consigned the poll tax and Thatcher herself, the so-called ‘Iron Lady’, to history.

We also had a decisive effect in influencing many workers and youth, particularly in the trade unions, to support Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour leadership challenge. On the Executive Council of Britain’s biggest union, Unite, we played a decisive role in securing its support for Corbyn in the first leadership election. We did the same in the main civil service union, the Public and Commercial Services (PCS) union, where we have significant influence, and in many other unions.

Labour’s working class roots

Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour conference speech, in which he attacked capitalism and called for “socialism in the 21st century”, followed Watson’s Blairite mantra that had been defeated in the leadership contest. Watson even suggested that the Labour Party was not “hostile to capitalism” or business. This was an ideological negation of the core reason why the Labour Party was formed at the beginning of the 20th century. It was precisely because the working class and the trade unions could no longer be accommodated within the framework of a stagnant capitalism and its impact on wages and conditions, that it broke from the Liberal Party and took the first steps towards the formation of a specific ‘Labour Party’. Up to then, they had directed their gaze towards the Liberals as a means of gaining piecemeal concessions.

The changed character of British capitalism, however, meant that the Liberals were no longer able to deliver. Hence the move towards a separate workers’ party, the Labour Party, which represented an implicit rejection of capitalism and embraced socialism in the period following the Russian revolution of 1917. This was enshrined in the constitutions of both the Labour Party and many of the industrial unions in Britain, some of which still include it today.

From the beginning, the ruling class was bitterly opposed to this development and exerted pressure on the Labour Party right-wing to eliminate the historical aspiration for socialism. A previous Labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, tried to remove ‘Clause Four’, which called for public ownership, from Labour’s constitution in 1959 but was defeated by the pressure of the socialist rank and file and the unions. It took Tony Blair’s counter-revolution for the wishes of the bourgeois to be carried out. He created in effect a new party, ‘New Labour’, with all elements of the left and socialism expunged. Blairism became the template internationally for similar processes within the workers’ parties and organisations, reinforced by the ideological effects of the collapse of Stalinism.

From its outset the Labour Party was, in Lenin’s phrase, a bourgeois workers’ party. Its mass base was composed of workers, particularly from the trade unions, while its leadership always had one foot in the camp of capitalism. Blair changed all that and created a ‘capitalist party’.

An incomplete victory

The Corbyn insurgency represents an attempt to turn back the wheel of history, to re-establish a new workers’ party. It was a spectacular manifestation of the law of unintended consequences. Jeremy Corbyn benefited from a change in Labour’s constitution which allowed non-members, workers and youth, for the first time to become ‘associate members’, with the right to vote in leadership elections, for the price of a pint of beer! Blair hailed the measure and regretted that he had not introduced a similar proposal, enshrining the idea of ‘one person one vote’. It was intended to further diminish the influence of the trade unions and to shut out their collective effect. For this reason, the Socialist Party originally opposed the introduction of this measure.

However, the mass of discontented young people and workers, completely alienated by the austerity of neoliberal capitalism, seized this weapon to ‘join’ the Labour Party en masse. In the process it dragged Jeremy Corbyn – up to then an isolated figure – into the light of day and raised him on their shoulders in a movement that can only be described as a mass uprising. This propelled him, through a series of mass rallies, into the Labour leadership.

The new relationship of forces was revealed by the fact that the open Blairite candidate, Liz Kendall, got a mere 4.5% of the vote in Corbyn’s first victory. This was, at the same time, just one expression of the delayed impact of the 2007-08 world economic capitalist crisis. Its effects in Britain – while not on the scale of Spain or southern Europe yet – are devastating on living standards, further impoverishing the working class and poor.

The Resolution Foundation think-tank revealed that six million working households are among the poorest half of the population and have experienced “a pronounced degradation in their incomes since the great crash of 2008… This has been accompanied by a significant rise in the cost of living, notably the amount spent on housing… The rise in housing costs since the turn of the century is the equivalent of 14p on the basic rate of income tax. That’s huge. Little wonder they are unhappy with the status quo”. (Observer, 2 October)

Faced with Corbyn’s victory, the right-wing set about organising the summer coup. Now, having won twice, Corbyn has offered places in his new parliamentary ‘team’ to the right-wing instead of consolidating his victory by going further to the left. History shows that failed coups will be repeated if the situation that led to them remains the same, and unless the plotters are decisively defeated. This is no less true of parties as it is of states. Spanish history attests to this. Spanish workers have no need to be reminded of the disastrous effects of the Popular Front government in 1936 that attempted to conciliate Generals Franco and Mola. This allowed them to prepare their coup leading to the strangling of the Spanish revolution.

The Labour right are not fascists, of course, and their attempts are not on the same scale. But they are in the camp of capitalism and bitterly hostile to socialism, particularly after the long period of dominance of Blairism in the British labour movement. If the opportunity is not seized now to shift towards the left, they can, with the help of the bourgeois, stage a comeback.

Initially, the British ruling class and its press urged the right to prepare to split and form a new right-wing party, like the Social Democratic Party in the early 1980s. However, the prevarication of Corbyn and his supporters and the 38% vote for Owen Smith, Corbyn’s opponent in the second leadership contest, have encouraged the right to believe that they could stage a comeback. The right are cut from the same ideological cloth as the social democrats in the rest of western Europe, whose social base has been dramatically undermined by the economic crisis of 2007-08.

Emerging left-populism

It is the effects of this crisis, taken together with the worldwide anti-capitalist movements preceding it, as well as the political rottenness of the leadership of the ‘traditional’ social democratic workers’ parties and organisations, which have led to the emergence of left-wing populism. This is a loose term employed to describe nebulous phenomena, not clearly left but appealing to ‘the folks on the bottom of the ladder’.

These transitional parties and organisations, inherently unstable, can give way through splits to a more defined form of left reformism. They contain elements of the past, alongside the undeveloped ideas and forces of the future. This is why we have described the present Labour Party as no longer a completely right-wing social democratic party but one which contains these features as well as the outline of a new radical socialist mass party. There are two parties fighting for domination within Labour.

The decisive shift towards the right in the 1980s and 1990s meant the Labour Party has not been a fruitful field of work for us for decades. Effective work was impossible in a moribund organisation which, under the tutelage of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, managed to lose five million votes and cover itself in shame through crimes such as the prosecution of the Iraq war, together with the adoption of a vicious neoliberal programme. Only a rump remained, composed of a largely petty-bourgeois caste of local councillors and demoralised functionaries backing Blair in his bloody rampage in the Middle East and the massacre of the living standards of the working class.

Blair’s Labour Party, in common with PSOE in Spain, Pasok in Greece, and most of the ‘traditional’ parties, moved decisively towards the right and was no longer a voice for the working class. In this situation, we and others like Arthur Scargill, the leader of the heroic miners’ strike in 1984-85, came out for a new mass socialist party. Moreover, this phenomenon materialised in outline in a number of countries, most noticeably in the PRC (Rifondazione Comunista) in Italy in the early 1990s. It has also found expression in Podemos in Spain.

But in Britain, the trade unions, particularly right-wing unions, clung to the shell of what once was a workers’ organisation. A similar process developed in Spain, although recent developments indicate that the so-called ‘Socialist Party’ (PSOE) is now being torn apart between its openly bourgeois wing, which wants to allow the right-wing Partido Popular to form a government, and those around the outgoing leader Pedro Sánchez, who understand that this would represent the kiss of death and the virtual disappearance of the party, as with Pasok in Greece.

Nevertheless, we hoped that the experience of creating new parties could, at a certain time, be repeated in Britain. However, the process was inordinately delayed, due to the ingrained conservatism of the tops of the trade unions in the main. We concluded therefore that it could not be excluded that a new formation could develop around a left radical figure. This is what we wrote in 2002: “Theoretically, Marxism has never discounted that, under the impact of great historic shocks – a serious economic crisis, mass social upheaval – the ex-social democratic parties could move dramatically towards the left”. (Can the Labour Party Be Reclaimed?, Socialism Today No.68, September 2002)

Unstable equilibrium

Genuine Marxism has nothing in common with rigid dogmatists who allow for only one possible form of organisation of the working class. Capitalism has been in crisis not just since 2007-08 but before, with recessionary features evident since the collapse of the post-second world war boom 1950-75. This has exercised a profound effect, changing the character of workers’ parties into ex-workers’ parties, which have become props for capitalism.

Then again, new parties can come into being but collapse quite rapidly if they do not respond to the desire of the working class for change. Syriza in Greece went from 4.6% in the 2009 general election to forming a government in January 2015. The betrayals of its leadership, however, have meant a colossal drop in support and it is now a significantly weakened force after the capitulation of the government of Alexis Tsipras to the EU austerity dictates in July 2015.

This is a warning to the working class. New parties may not last if they do not work out a clear programme. They can face atrophy and collapse or be replaced by more radical formations. The character of our era of crisis-ridden capitalism does not, in the main, allow for stable formations. Present now is an element of the 1930s: objectively pre-revolutionary, particularly in the economic sphere, if not yet fully in terms of the consciousness of the mass of the working class. Medium- or long-term perspectives therefore can be measured in months rather than years.

The unstable equilibrium between the left and right cannot last for any length of time. The Momentum organisation around Corbyn, which in effect seeks an accommodation with Labour’s right-wing, can stand still or retreat on the demands of the more conscious layers of the working class for urgent action against the right, both in ideas and organisation. Indeed, the lack of a mechanism to remove the Blairites – particularly Labour MPs – means leaving the power of the right-wing intact to plot and further undermine Corbyn, striking a mortal blow against him when they decide the time is ripe.

The organisational character of a broad party or even a federation plays a crucial role in who ultimately exercises control and power, as the history of the Spanish workers’ parties illustrates. This was shown before and during the Spanish revolution. While Largo Caballero enjoyed the support of the rank-and-file socialists, he neglected to reflect this within the structures of the party.

Tony Saunois pointed to this in the July/August 2016 issue of Socialism Today: “The divisions in PSOE between these two wings prior to the fascist revolt were heading towards a split in the party. Prieto succeeded in forcing a postponement of the party congress. The executive outlawed Caballero’s newspaper, Claridad, and reorganised the districts controlled by him. Then, as the revolution and civil war broke out, Caballero’s wing, despite having a majority in PSOE, allowed Prieto to keep control of the party headquarters on the basis of maintaining ‘harmony’. They then desisted from any further steps to take control of the party. There are lessons here for Britain today and Jeremy Corbyn’s attempt to appease the Blairite right-wing of the Labour Party and not confront them” (1936: Spain’s revolutionary promise). The representative of the right, Indalecio Prieto, maintained control of the party machine, which he used to strengthen the right and weaken the influence of the left, and thereby the Spanish revolution.

The reselection of MPs

It is a law that the working class, particularly in periods of radical upheaval, is immeasurably to the left of their mass parties. Even in the most revolutionary party the ranks can be to the left of the leadership. Certainly in Britain, the young people who have flocked to Labour are more left-wing than their erstwhile ‘leaders’. Owen Jones and Paul Mason are typical of this type, as are the leaders of Momentum.

Jones toured Spain during its last election in support of Podemos and has a certain profile as a semi-official spokesman for the left in Britain – up to now. But he has moved towards the right, as has Mason, echoing the demands of the right-wing for ‘unity and peace’ and opposing the democratic re-selection of MPs as party candidates before every election. Jones wrote that mandatory reselection “must be resisted”. (Guardian, 26 September) He endorses the demands of the right that they remain in place. This is music to the ears of the right who have compared the exercise of the democratic rights of the rank and file with MPs facing a ‘firing squad’.

Compare Jones and others to the position of Len McCluskey, head of Unite the union and a supporter of Militant during the Liverpool battle of the 1980s. He coupled a rousing call for socialism at the Labour Party conference with the declaration that the MPs who plotted against Corbyn “had brought [reselection] on themselves”. He was promptly criticised by Momentum’s Jon Lansman!

From the outset, the leaders of Momentum arrogated to themselves the leadership of the Corbyn movement on the basis of their alleged ‘expertise’ in matters of organisation, both in the Labour Party and in the victory for the left. But they opposed reselection from the start with Lansman, their chief spokesperson, expressing opposition to us joining and supporting the Corbyn movement and the Labour Party. He claimed to want to re-establish ‘social democracy’ in opposition to Blairism. Our simple question in the discussion we had with him was, could he provide a model, a country, in which this was still on offer?! Social democracy has proved completely incapable of carrying through consistent reforms. Why? Not just through any personal deficiencies of leadership but because capitalism today demands counter-reforms, as the experiences of Spain, Greece, Britain and the US illustrate.

Tory EU splits

The support for left populism – as reflected in the Corbyn, Sanders and Podemos movements – reflects a yearning for change in a radical socialist direction on the part of the youth in particular, with big sections of the working class joining them. The leave vote in the EU referendum represented at bottom an uprising against the elite by the working class alongside sections of the middle class.

They perceived the imperialist EU as an author of their misfortunes and took the opportunity to strike back against it and the British ruling class. Incredibly, sections of the left – including some alleged Marxists – opted for remain. They agreed with our analysis that the EU represented a brutal neoliberal project. Its constitution seeks to outlaw any government which challenges the market and looks towards a socialist solution. However, they pessimistically reasoned that Boris Johnson & co would emerge triumphant and a ‘carnival of reaction’ would flow from this. Such was the position of Paul Mason, and even some left trade union leaders, as well as tiny ‘Marxist’ organisations, who are hardly visible in the political maelstrom which is Britain today.

The Socialist Party, on the other hand, came out firmly against the EU and for a leave vote – on a class, internationalist and socialist basis. Moreover, we predicted that a defeat for remain would be a death blow to Tory prime minister David Cameron, thereby opening up a favourable prospect for left-wing and workers’ struggles. This is what actually happened as Cameron abandoned the government a few days after he was defeated.

If Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell had come out in opposition to the EU – as they did alongside us in the referendum on the Common Market in 1975 – it would have fundamentally changed the situation. It could have prepared the way for increased support for the Labour Party, with the Tories in disarray, and forced a general election in which Labour would have had the opportunity of winning, as even some commentators in the Financial Times admitted. Corbyn however, imprisoned as he was by the right-wing parliamentary cabal, gave lukewarm support to the remain side, for which he was brutally criticised.

The net outcome of the referendum was the side-lining of Boris Johnson with Theresa May coming to power. But after a short honeymoon, divisions on Europe and other issues are visible. The capitalist media have been able to concentrate on the splits within the Labour Party but they will not be able to hide these divisions within the Tory ranks from breaking out in the next period. The negotiations over Brexit could result in Britain leaving the EU, which will have colossal repercussions in the Tory party, and probably split it from top to bottom. This could result in a schism similar to that of the early 19th century over the Corn Laws which kept the Tories out of power for decades.

An ongoing battle

Therefore after Labour’s conference, the capitalists urged the right to form a rival right-wing organisation, Labour Tomorrow, to counter the left. Newspapers, some of them nominally pro-Labour, like the Daily Mirror, are also suggesting a deadline of 2018, by which time, according to them, Corbyn will have had ‘ample opportunity’ to demonstrate his popularity or otherwise. Through rigged polls – which were wrong on the Scottish referendum and the general election – Corbyn will have been judged by them to be ‘unelectable’ and they hope his painless removal as Labour leader could take place.

Momentum is playing into the hands of these transparent manoeuvres. There are still conservative layers within the working class upon which the right-wing social democracy hope to lean in its battles with the left. They have behind them all the forces of bourgeois society – including the media – and, potentially, the more conservative sections of the working and middle classes. So the battle is ongoing, the civil war continues and may not be resolved quickly. The quite lengthy test of wills can be played out and the Socialist Party will play its full role.

Prior to the changes effected by the Corbyn movement, we had successfully organised the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) with the Rail Maritime and Transport workers union (RMT) as well as the Socialist Workers Party and other good trade unionists. Its main campaign was to fight the cuts which have been carried out both by Labour and Tory governments. The Socialist Party linked this to the campaign, centred particularly on the unions, for a mass working-class party. To this end, we stood in a number of elections in opposition to Labour. But when Corbyn’s challenge was made for the Labour leadership we supported this.

Now, after Jeremy Corbyn’s second victory, we have suggested to TUSC that preparations for future electoral challenges should be suspended, in order for the time to be given to carry through necessary changes – like reselection – to consolidate the victory of the left. The situation is very fluid and it is not assured that Corbyn and his supporters will get their own way against the right. At the Labour Party conference Momentum was outmanoeuvred by the right, who consolidated their small majority on the National Executive Committee, with Jeremy Corbyn abstaining on a key vote which resulted in two more places for the right-wing from Scotland and Wales.

Moreover, a resolution was smuggled through with organisational proposals – without proper discussion or debate – outlawing Labour councils adopting ‘no-cuts budgets’. These were adopted by Liverpool city council in the 1980s to defeat cuts and Thatcher. This resolution can now be used by rotten Labour councillors – the majority of Labour’s 7,000 – who act as quislings, and collaborate in implementing the cuts programme of the government and the ruling class. While we are prepared to be part of what could be a huge shift towards the left, this cannot be at the cost of not participating in and seeking to lead movements of the youth and the working class in resisting the onslaught of capitalism, linked to the fight for the socialist transformation of Britain, Europe and the world.