Non-fiction review: Lenin on the Train

Tense, lively prologue to events which changed the world

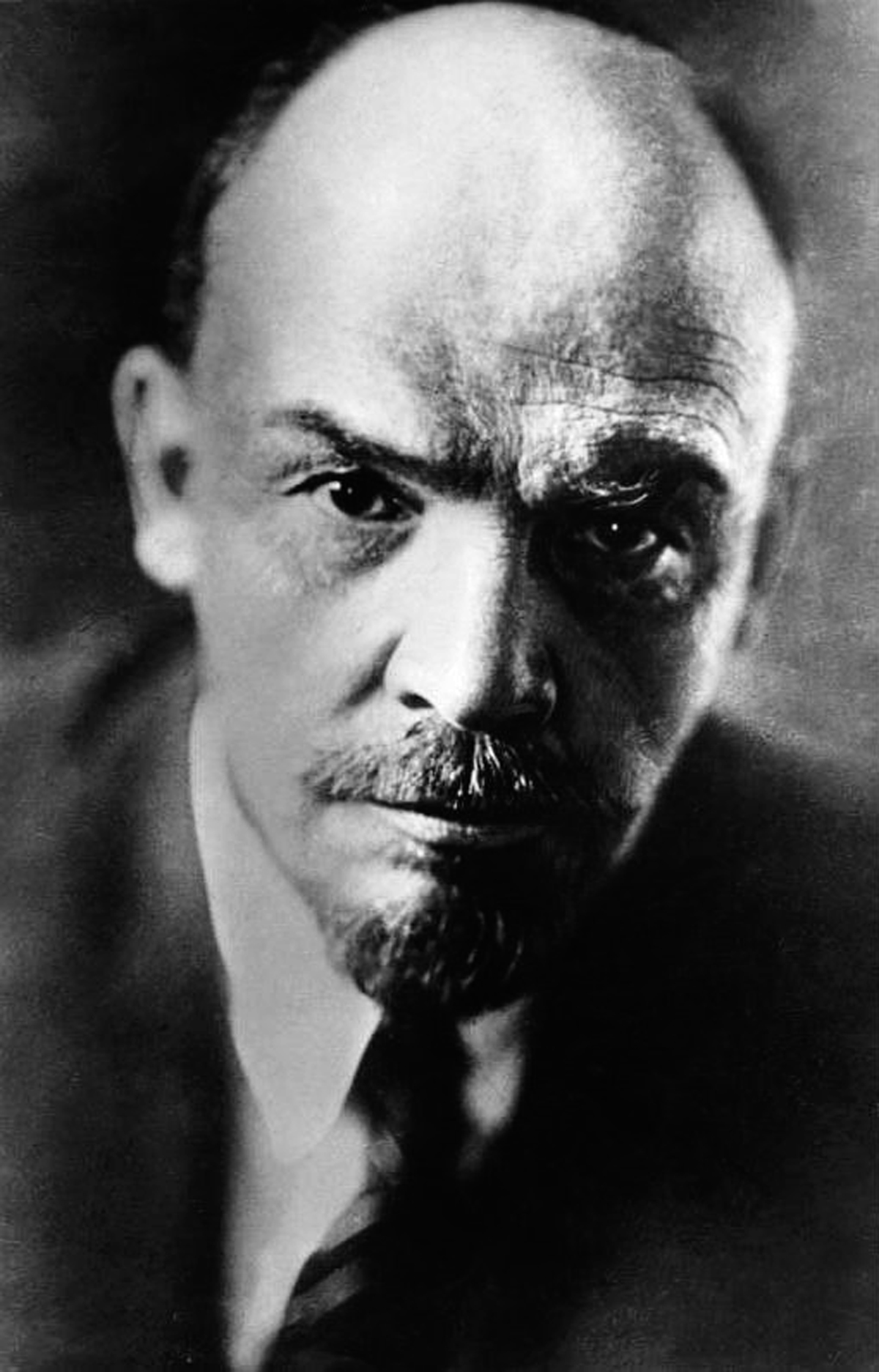

Vladimir Lenin, one of the central leaders of the 1917 Russian revolution, photo by German Federal Archive (Creative Commons) (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

Niall Mulholland

When the February revolution broke out in Russia in 1917 and the Tsar was overthrown, Vladimir Lenin was living in exile in Switzerland.

Given his implacable opposition to the imperialist World War One, it was always going to be a major feat for the Bolshevik leader to return to Russia across countries at war, to lead the principled socialist opposition to the new capitalist Provisional Government.

In ‘Lenin on the Train’, Catherine Merridale gives a lively narrative of Lenin’s efforts to get back to revolutionary Russia – “a journey that changed the world” – despite her condemnation of the Bolsheviks once they were in power.

She brings out the crucial role of Lenin, from abroad and on return to Russia, in politically re-orientating the Bolsheviks, so that they were able to go on to lead millions of workers, soldiers and poor peasants and take power in October.

Caught unawares

The Tsarist regime and British diplomatic sources were largely caught unawares by the February revolution, which broke out over food shortages and as seemingly endless war exacted a huge death toll. And they were in denial.

“The striking feature of the British diplomatic and intelligence correspondence at this point was its refusal to accept the finality (let alone legitimacy) of the February Revolution as a whole,” Merridale notes.

Lenin urgently looked for a way back to Russia and explored several options. He was approached indirectly by the notorious intriguer and former Marxist thinker, Alexander Helphand (also known as Parvus), who suggested striking a deal with the German regime to allow Lenin and other socialists to return to Russia in a ‘sealed’ train across German territory.

The German generals, looking over their shoulders as the USA prepared to enter the war, gambled that the return of Lenin and other revolutionaries would worsen Russia’s turmoil, forcing the country out of the war. They got much more than they bargained for – a socialist revolution in Russia which inspired the overthrow of the Kaiser and a revolution which threatened the existence of German capitalism.

Merridale shows how Lenin was extremely hesitant about taking up this offer, as he correctly feared it would be used by his political enemies to denounce him as a “German agent.” But faced with no other viable option to get back to Russia, Lenin very reluctantly went along with the scheme.

However, he insisted at all times on his full political independence from German imperialism and its interests.

Lenin continued to write and publicly speak on how he opposed all the imperialist warring nations, including Russia and Germany.

He insisted the revolutionaries travelled by third-class coach in the train and that a chalk line drawn across the floor of the carriage separated the Russians from their German military ‘minders’.

Merridale discusses in detail the allegation made by Lenin’s enemies in 1917, and ever since, that he received “German gold”. She concludes that “instead of proof there were only probabilities and lies” to back up this claim which is used to try to discredit Lenin and the Bolsheviks, and to airbrush the role of the masses in the revolution.

Furthermore, she comments that Lenin was no more an agent of imperialism than Georgi Plekhanov, the ‘father of Russian Marxism’, who was sent back to Russia with the aid of imperialist Britain. For Plekhanov, “though a Marxist, was a sound man on the war, a patriot who could tell other socialists exactly where their duty lay.”

As well as the Provisional Government, the February revolution threw up the soviet (council) of workers’ deputies, a “dual power” rivalling the capitalist administration. But on the day Lenin’s train pulled out of Zurich station, 27 March, the Provisional Government declared, with “an endorsement in the name of the soviet,” it would continue the war.

Lenin insisted that the Bolsheviks must resolutely oppose the treacherous Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries at that time leading the soviets.

Merridale describes Lenin’s growing exasperation with the vacillating leadership of the Bolsheviks in Russia, particularly Kamenev and Stalin. In the pages of the party paper, Pravda, Kamenev argued that Russia “would still have to fight and win its war, albeit mainly to defend the gains of the revolution…”

Although Kamenev was “censored” by the local party (“and Stalin silently abandoned him”), confusion reigned inside the Bolsheviks until Lenin’s return. Lenin’s “telegram of early March had been explicit: no support for the Provisional Government, no cooperation with other parties… for a transfer of power from the bourgeois to a workers’ militia or to soviets…

“The whole line ruled out any coalition with the Mensheviks. The war, he had insisted, was a bloody capitalist adventure, and not what Kerensky was now calling a fight for revolutionary self-defence.”

Jubilant

On reaching Finland Station, Petrograd, Lenin told a large jubilant crowd to prepare for socialist revolution. “His slogans felt like a sudden electric shock… a call to life, a blinding glimpse of futures some had privately begun to doubt,” Merridale writes.

The last chapter brings out Merridale’s political hostility towards Lenin. She claims the October revolution was a “coup” that led to “dictatorship.” In doing so, Merridale dismisses a genuine revolution involving millions and conflates the early years of working class rule with later Stalinist counter-revolutionary tyranny.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that the October revolution marked the first time the working class came to power successfully and started to carry out the socialist transformation of society against enormous odds.

- ‘Lenin on the Train’ – hardback £25 or £10 paperback due in April. Order from Socialist Books, PO Box 24697, E11 1YD, [email protected] or leftbooks.co.uk