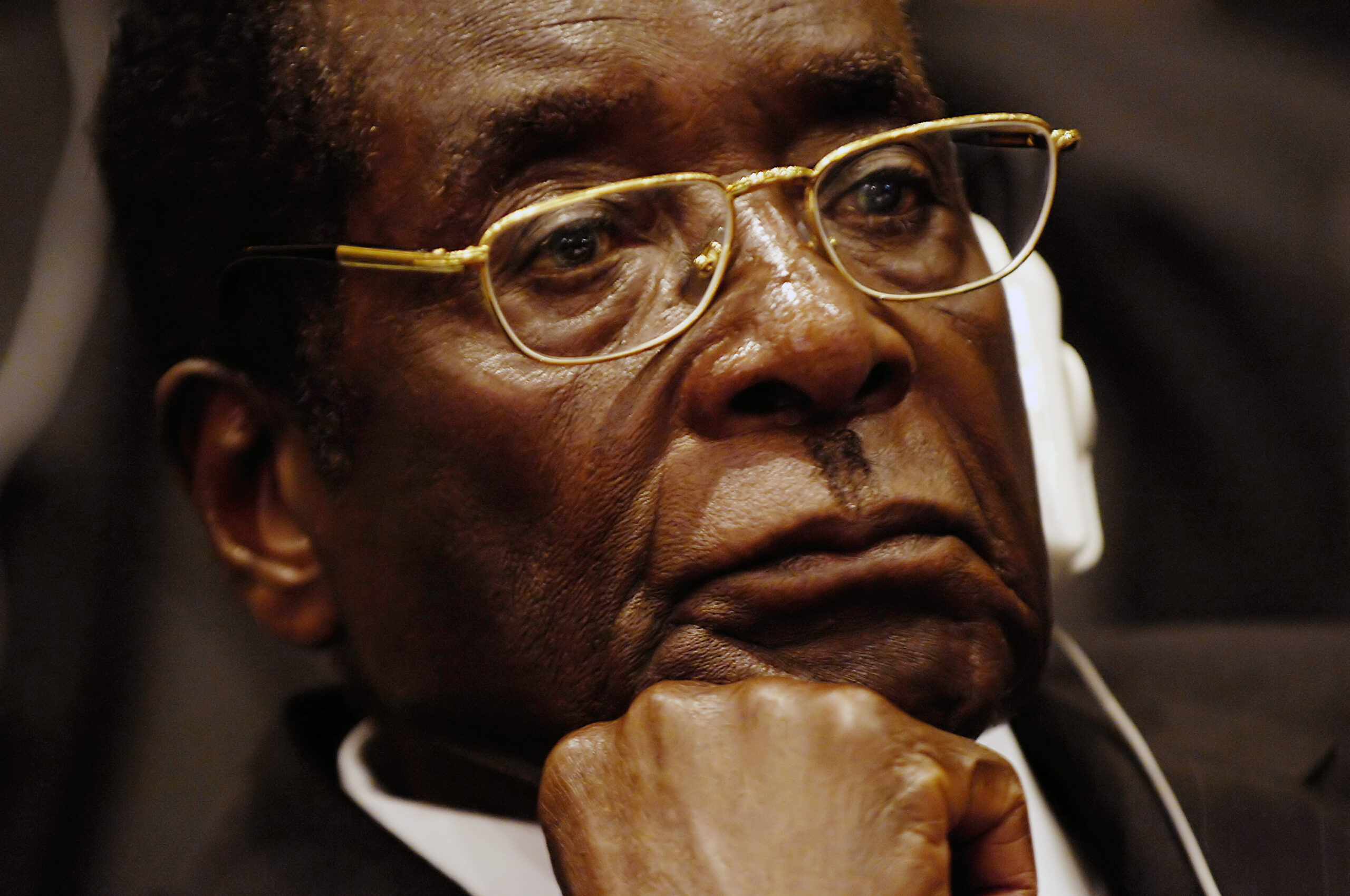

Zimbabwe’s autocratic president Robert Mugabe has effectively been ousted through a ‘soft’ military coup led by the old guard Zanu-PF faction gathered around Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Mnangagwa too has a history of organising brutal repression against political opponents and Zimabawe’s organised working class.

Nonetheless, Mugabe’s removal may embolden independent workers’ organisations to renew their struggles against the regime, as Weizmann Hamilton and Tinovimbanashe Gwenyaya of the Workers and Socialist Party (CWI South Africa) explain.

The takeover of power by the Zimbabwe Defence Force represents a turning point in post-independence Zimbabwe.

The military takeover was precipitated by the dismissal of Mugabe’s most loyal henchman for the past 37 years, Emmerson Mnangagwa.

This was part of 93-year-old Mugabe’s manoeuvres in Zanu-PF party structures to ensure his 52-year-old wife Grace would succeed him as president.

However welcome the end of Mugabe’s reign may be, the military’s intervention is taking place behind the backs of the masses. To pre-empt the independent movement of the masses, such as the 2016 Tajamuka protests, the military is drawing the elites, including the opposition, into a political arrangement to impose on the masses a dispensation whose primary aim is to maintain the capitalist status quo.

However, Mugabe’s removal may be the trigger that reignites mass movements. Even the choreographed ‘war veterans’ demo opened up political space for widespread protest against the entire ruling clique.

Mugabe’s actions had in the recent period become increasingly erratic. He had presided over an economy that experienced the highest inflation rate in world history rendering the Zimbabwe dollar completely worthless.

It led to the forced abandonment of the currency and its substitution with the US dollar and the SA rand.

The catastrophic economic collapse, 90% unemployment and mass starvation led to a mass exodus, mainly to South Africa, of at least a quarter of Zimbabwe’s 12 million population.

These developments are taking place against the background of a deepening economic crisis that has compelled Mugabe to go cap-in-hand to China and the West, including the International Monetary Fund, for economic aid and the lifting of sanctions.

The events leading up to Mnangagwa’s sacking and those which have followed are the cumulative outcome of the Zanu-PF government’s successive failures since the ‘liberation movement’ assumed power nearly four decades ago.

The initially popular Mugabe won successive landslide victories in elections until in the mid-90s he implemented a brutal IMF/World Bank neoliberal ‘economic structural adjustment programme‘ which provoked the biggest workers’ protests in Zimbabwean history.

However the turn of Zimbabwe’s then trade union leaders towards collaboration with capitalists and rich farmers against Mugabe disarmed this movement and allowed Mugabe to pretend he was a champion of the poor.

Since then Mugabe has been able to stay in power by increasingly authoritarian methods backed up by the very same military that has now moved to oust him.

Mugabe’s decision to pick his own successor was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Grace Mugabe’s exponential rise to power thus played a decisive role in the expulsion of Mnangagwa, precipitating the succession crises now unfolding in Zanu-PF.

Drunk with the euphoria of power, Grace Mugabe and her G40 faction seemed to have assumed Mugabe’s role itself in dictating the programmes of Zanu-PF and by extension those of government.

Mnangagwa, who claims to have survived food poisoning a few weeks before his sacking, has been leading a faction called ‘Lacoste’ – which is backed by the military, and securocratic elements within Zanu-PF and who have played a leading role in Mugabe’s reign of terror.

With Mnangagwa’s flight into exile after his sacking it first appeared that his faction was on the back foot and had been relegated into the political wilderness.

But as subsequent events illustrate, Mnangagwa’s military backers were not willing to accept defeat.

The Lacoste faction appears to have moved with the tacit consent of not just South Africa, but also after consultation with China. Mnangagwa himself is reported to have been flown back to Zimbabwe in a South Africa national defence force military plane.

The military claims that this is not a coup, merely an intervention to clear out the “criminal elements” that surround Mugabe.

This appears to be carefully crafted to allow the Southern African Development Community (SADC), chaired by South Africa’s president Jacob Zuma, to allow the military to complete their mission without coming under pressure to take some kind of action to show their disapproval for ‘regime change’ by unconstitutional means.

A military intervention is ruled out. SADC has not even been able to stabilise Lesotho. A military intervention to force regime change in Zimbabwe would ignite a conflagration they would have no control over.

It is far more likely that the Zimbabwe Defence Forces will be given the time to stabilise the situation by managing Mugabe’s exit and to prepare for the elections due in 2018 with Mnangagwa as caretaker president.

Stabilising the situation will entail a purge of the G40 faction – a process that has already begun.

The Zimbabwean masses have largely been spectators in the factional battles of Zanu-PF and have in recent days watched and danced with delight at what appeared to be a self-inflicted implosion and the almost guaranteed demise of the Zanu-PF state.

Sections of the masses will welcome this development seeing in it the lifting of the yoke of the Mugabe dictatorship.

But this would be a mistake. Mnangagwa led the Gukurahundi operation during the 1980s murdering an estimated 20,000 Ndebele people.

At the same time there is deep distrust in the military and few illusions that it represents hope or an end to the misery of the Mugabe regime.

The military has been critical in sustaining the Mugabe dictatorship, including carrying out systematic terror.

Thus there should be hardly any illusions as to whether or not the military represents a tenable alternative for the working masses and poor.

A recent report revealed that the illicit outflow of diamond revenue was used to prop up the regime and companies which were linked to the military and the Central Intelligence Organisation.

Neither a transitional government nor its successor will be able to solve the problems of poverty and mass unemployment.

The atrocities of the military remain well documented; its role in kidnapping and killing opposition supporters, particularly during elections, remains unquestionable.

The military coup is not at all a change of the Mugabe-Zanu regime’s character but represents its continuation and attempt at the regeneration of the military’s control over it in a manner they hope will be self-sustaining.

Its purpose is to guarantee the continuation of its autocratic rule and not to usher in a new democratic dispensation under the control of Zimbabwe’s masses.

The experience of recent years shows that many of the working class of Zimbabwe understand this very well.

This was evident in 2016 when there was a massive uprising and grassroots mobilisation in rejection of Mugabe’s regime.

The military responded to this by standing firm and emphasising its allegiance to Zanu-PF and Robert Mugabe.

The lesson both of last year’s mass mobilisation, as well as the whole of Mugabe’s tenure, is that reliance on external forces such as SADC and neighbouring governments is futile and regressive.

All the administrations of the South African government – from Mbeki through to Zuma – have propped up the Mugabe regime.

The South African Communist Party followed suit, demonstrating its contempt for the Zimbabwean masses by denouncing the mass demonstrations as recently as last year as the work of a “third force” bent on regime change.

The masses are their own liberators, the Zimbabwean experience of the last two decades confirms this.

As previously emphasised by the Workers and Socialist Party, the masses of Zimbabwe can only rely on their own programme, their own power and their own organisation to overthrow the capitalistic dictatorship and achieve the socialist transformation of Zimbabwean society.

Zimbabwe’s workers, young people, and the diaspora must now congregate towards building a mass workers’ party.

Such a party must learn from the lessons of the failed attempt in the late 1990s to build one. It is vital to ensure a new workers’ party strives to lay the foundations of a government of workers and poor on a socialist programme so as to inflict a decisive defeat of the post-Mugabe regime currently emerging.

This version of this article was first posted on the Socialist Party website on 21 November 2017 and may vary slightly from the version subsequently printed in The Socialist.