Brazil’s most polarised and unpredictable election campaign in recent history has ushered in a new era for the country.

The far-right candidate, Jair Bolsonaro, an ex-army captain who defends the military dictatorship and its methods of torture and extermination of the left, leads in the first round with 46% of the vote. He came within a short distance of winning an outright victory.

This development poses a clear threat to the working class and will pose new challenges for the workers’ movement.

Between 42% and 46% of the electorate say they wouldn’t vote for him under any circumstances and a significant level of abstention took place.

In the election the traditional parties of the ruling class saw a collapse in their support.

Although the radical left Party of Socialism and Liberty (PSOL) candidate, Guilleme Boulos, fell to just under 1%, PSOL made significant advances. The number of federal deputies rose from six to eleven.

In São Paulo it increased its number of federal deputies from one to four. PSOL’s campaign has involved thousands of supporters of social movements.

But it suffered from the enormous pressure for lesser-evilism to defeat Bolsonaro. The fear of Bolsonaro’s victory has tended to outweigh the enormous sympathy which exists for the PSOL candidates.

His electoral growth has served as a provocation for big sections of the population repelled by his right-wing, anti-working-class policies and his misogynistic, racist, anti-LGBT+ rhetoric.

His rejection ratings are 52% among women compared to 38% among men. Already, ‘anti-Bolsonaro’ committees have been formed in many areas.

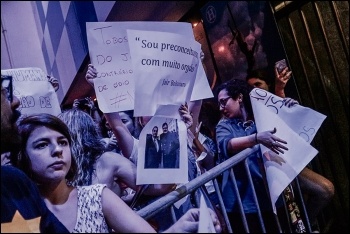

Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in all the state capital cities and thousands more in other municipalities on 29 September.

It is estimated that overall one million people, a majority women, youth and workers, took to the streets under the slogan of #EleNão (#NotHim).

Bolsonaro’s social base is mainly made up of older men from the middle classes and richer strata of society, concentrated in south and south eastern Brazil, where there is a bigger middle class.

Rejection of Bolsonaro is very high among women and the poorest – 55% of those who make less than double the minimum wage – and in the north east, where he is rejected by 61%.

Bolsonaro was stabbed in his stomach when he was campaigning on 6 September. The commotion generated by this attack helped him.

His capitalist opponents had to hold back their attacks and criticisms. And he used it as an alibi to not participate in debates with other candidates.

During this campaign Bolsonaro has adopted more explicit neoliberalism, distancing himself from ‘strong-state nationalism’ which was typical of a section of the Brazilian military, including during the 1964-1985 dictatorship.

Despite being a candidate backed by the rich, a reactionary, and a defender of deeply anti-people measures, Bolsonaro is still seen by a wide section of the population as anti-system and outside the establishment. Despite being an MP for 28 years, he has built an image of

being outside the games of the professional politicians, big business and establishment media.

He links the “left” with corruption. He adds to this an image of someone who will confront the problem of ‘security’ with an iron fist.

He uses the issues of corruption and violence, two real problems, to capture the electoral support of the middle class and some sections of the poor who are more and more filled with fear and hatred.

The sentiment of opposition to the system has predominantly so far been captured by the right wing – mostly due to the limits and slow pace of building a new radical anti-capitalist and socialist left.

The opposition to Bolsonaro is still dominated by the Workers’ Party (PT – the former ruling party of Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff), characterised by the defence of class collaboration and institutional actions which are not differentiated from the rotten political system.

The PT emerged as the largest block in the Chamber of Deputies with 57 MPs. The PT’s Presidential candidate, Fernando Haddad, finished second.

The sharp decline of the PT, following corruption scandals and convictions, has been stalled and reversed among some voters.

The main reason for this turnaround is the total disaster of the right-wing Temer government.

Temer overthrew Dilma in a 2016 coup-style impeachment manoeuvre and has applied a tough programme of cuts and attacks to social rights during a deep recession.

The PT responded to the 2016 coup by prioritising negotiation among the elite to recompose its support in Congress and other institutions.

They were facing popular opposition to the austerity imposed by Dilma. This has been their approach in the struggle against impeachment and in the ‘Fora Temer’ (Temer Out) movement.

The PT tries to convince the ruling class that Bolsonaro is too risky. The Brazilian capitalist class did everything it could to establish a trustworthy candidate – one more organically linked to the ruling class with a clear neoliberal programme.

However, they failed in this project. Geraldo Alckmin – candidate for the Social Democratic Party, the main party of the Brazilian capitalists – got less than 5% support.

Despite the conciliasionist line of the PT, polarisation is becoming extreme. Fighting Bolsonaro, who has a real chance of winning, will become the priority for millions.

These people will become politicised and ever-greater numbers will understand the limits of the PT – opening up greater opportunities for the socialist left, which is not soaked in class collaboration, to make big gains.

Should Bolsonaro win, his government will go onto the offensive and introduce far more repressive measures.

It will represent a turning point in Brazil and throughout Latin America. A movement to fight this repression needs to be built including with the formation of self-defence committees.

As a warning to the left in other countries, the right wing in this campaign used the disaster of Venezuela, which it argued is the consequence of socialist policies. In reality it is the consequence of a failure to break with capitalism.

The threat of a Bolsonaro government means that in the second round, LSR is fighting for a vote against Bolsonaro and for a movement to be built to prepare a struggle against such a right-wing, repressive government.

Brazil is passing through a period of extreme instability and volatility. Sudden changes can occur. The revolutionary socialist left, and LSR in particular, must prepare for the great battles which are approaching.