Jagadish Chandra, New Socialist Alternative (CWI in India)

This year’s planned general strike on 8 January was massive. It broke all previous records in the numbers involved in united class action in India.

The strike was called by ten major trade union bodies under the banner of the Joint Committee of Trade Unions, linked to many opposition parties.

The main demand was the “reversal of the anti-worker, anti-people, anti-national policies of the government,” including the dropping of any decisions for the privatisation of the state-owned companies Air India and Bharat Petroleum.

Undoubtedly, the general strike was a huge success numerically. The overall participation in the strike of 250 million was an increase of 30 million from the 220 million of 2019.

Inevitably, both the state and the administration across the country worked overtime to see that the visible impact of this collective class action was minimised.

Attacks

Over the years, as crisis-ridden Indian capitalism has begun to offload its burden onto the urban working poor and the beleaguered rural peasantry, the general struggle of resistance has taken many forms.

It has shown itself in many intensified cross-class struggles that have taken place throughout the country, not necessarily led in an organised way or expressing clear demands.

But the poor expressed their anger and frustration in the form of localised bandhs (stoppages), ‘railrokos’ (stopping trains) and many times state-wide and country-wide bandhs.

While industrial workers of many different sectors all over the country went on strike, the peasants and agricultural workers massively responded to the call of a ‘rural bandh’ and organised road and rail blockades (see socialistworld.net for a comprehensive list of sectors and states affected).

Linking struggles

The trade unions put forward a 12-point programme of demands on basic economic and work-related issues.

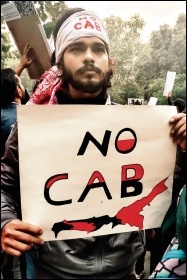

In the midst of the mass protests sweeping the country against the government’s attacks on democratic rights, the unions also protested against the outrageous onslaught by Modi’s BJP government on the basic tenets of the constitution through the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the national register of citizens (NRC) and the national population register (NPR).

The CAA allows citizenship to people who have fled to India from persecution in Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan before December 2014. However, this does not apply to Muslims, rendering them stateless.

The state apparatus was extremely worried about the social and political fall-out if the forces of the general strike and those of the sporadic and spontaneous movement against the CAA had joined together.

Despondency

The last six years of aggressive, neoliberal economic attacks, mixed with non-stop majoritarian Hindutva communal onslaughts, had numbed even the most politically advanced sections.

Given the absence of a leadership with a far-sighted perspective to combat and thwart the juggernaut of Modi’s right-wing Hindutva (promoting the dominance of Hindu culture) regime, naturally a sense of despair existed among some workers and youth.

The twin fiascos of 2016 – demonetisation* and the Goods and Services Tax – that brought enormous misery to the middle class and the poor across the country, went almost unchallenged.

What could have been a real opportunity for the left to mount a challenge against the Modi regime was instead frittered away, without any serious attempt to build a struggle.

This is particularly the case with demonetisation which caused more than 180 deaths in the span of ten weeks, including ordinary bank workers.

The irony is that 70% of bank employees are organised under the banner of two unions – the All India Bank Employees Association and the Bank Employees Federation of India – aligned to the left parties CPI and CPI(M).

Following that missed opportunity, traders and vendors were up in arms against the notorious Goods and Services Act, which resulted in massive job losses in the service sector of the economy to the tune of almost five million jobs. This too went largely unchallenged.

It is in this context that the second victory of prime minister Narendra Modi in the May 2019 general election has to be seen.

Soon after, Modi went on to abrogate the constitutional guarantees to the people of Jammu and Kashmir – which of course led to mass protests in the occupied territories that are still being brutally suppressed.

Many of those in opposition to Modi’s regime are either under house arrest or behind bars.

With this forced silence and with a parliamentary opposition that had no idea of putting up a fight, the left gave up even the thought of extra-parliamentary struggle.

Anger erupts

Then Modi’s sinister move to surreptitiously bring in the Citizenship Amendment Bill, and then bulldoze it through parliament with just a mere seven hours debate, triggered the anger of the masses.

It started in the state of Assam, which had already seen the disastrous exercise of a National Register of Citizens.

Across the country angry youth spontaneously poured on to the streets with a clear battle cry of “enough is enough!” The protests are still raging unabated.

It is very clear from the course of events that the left in general has been found wanting. The general strike meant it had an opportunity to change the scenario from one of helplessness to an all-out struggle against the Modi regime.

It’s no exaggeration to say that if the left and the trade unions had given a lead, taking with them the anti-CAA protesters on the basis of a clear programme for the scrapping of the CAA, it would have had an electrifying effect among both the organised working class and the non-organised mass of people, who have formed the bulk of the anti-CAA protests.

The 250 million figure for the numbers participating in the general strike would then have easily been double that number.

Instead, the left parties, and thus the trade union leaders, were too reluctant to mount an all-out challenge against the Modi regime.

Only after being forced by sections of the rank and file, did they include at the last minute a demand against the CAA – added as the 13th demand and extending the customary solidarity in order to save face.

It was criminal not to campaign against the CAA with all their class might. It shows how out-of-touch are these so-called ‘communist parties’ are with the situation on the ground.

They act and behave like any other opposition party based on the middle class, without any perspective of struggle or a combative programme to unite the masses.

They are fetters on the working class and the oppressed, preventing them from finding the road to a revolutionary change in society.

New Socialist Alternative’s (CWI India) leaflet, demanding the scrapping of the CAA, explained that the ongoing country-wide protest against the Modi regime is full of radical potential.

The urgent task for the Marxist fighters around New Socialist Alternative is laid out very clearly. We must reach those combative youth and convince them of the need for the struggle to scrap the CAA/NRC/NPR to be fought on class lines, with clear demands.

* The withdrawal and replacement of higher currency notes – which was meant to expose unaccounted wealth – failed. Instead, it cost the economy over 1% in total output and led to 1.5 million job losses.