30 years ago the historic struggle against the hated poll tax was reaching its peak. Below is an edited version of a foreward by Dave Nellist to the new book “Couldn’t Pay, Wouldn’t Pay, Didn’t Pay” compiled by Eric Segal, secretary of the South East Kent Trade Union Council. Dave, a member of the Socialist Party and its forerunner Militant, was the Labour MP for Coventry South East from 1983-1992 and became the main parliamentary spokesperson for the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation. Here he outlines the most important stages in the battle to defeat the poll tax and its lessons for struggle today.

The battle against the poll tax was the biggest civil disobedience campaign of the 20th century. In a normal year in the 1980s the number of cases (summonses) brought before the magistrates’ courts of England and Wales was about two million. But between April 1990 and September 1993 the number of cases of unwillingness, or inability, to pay the poll tax taken before the magistrates (in just England and Wales) totalled an additional and staggering 25 million.

It is estimated this involved 14 million people, many with multiple summonses. That’s just under one-third of the entire adult population. The sheer volume of cases overwhelmed the legal system; universal enforcement of the poll tax was made impossible, and what had once been described as Margaret Thatcher’s ‘flagship’ policy was sunk.

In November 1990, as Margaret Thatcher was forced to resign, the captain went down with the ship.

How did a government with a 102-seat majority and a seemingly strong, commanding leader, suffer one of the greatest defeats in modern times? Such results are not accidents, they don’t fall from the sky. They require planning and organisation.

The poll tax

The poll tax was introduced in Scotland in April 1989, and England and Wales a year later. It was never risked in Northern Ireland. The poll tax replaced the domestic rates system, which had been a means of raising income for local services based on the size of residential property, so roughly related to income.

The poll tax, however, was a head tax – a flat rate – which meant a millionaire paid the same as the poorest 18-year-old. The poll tax affected young and old, employed and unemployed, the sick and disabled, council tenants and homeowners. It was widely seen as unfair. It was estimated that Thatcher’s own family in Dulwich would save £2,300 a year, while working-class families with adult sons or daughters living at home could have an extra bill of many hundreds of pounds.

Building the campaign

The campaign against the poll tax in Scotland was launched in Edinburgh in December 1987. The new tax in Scotland, and later in England and Wales, was to have the effect of providing a single issue – a lightning rod – for accumulated hatred of Margaret Thatcher and the Tories for the defeat of the miners, the pauperisation of local services and councils, rising unemployment, the decline of manufacturing employment and industries, and the privatisation of utilities.

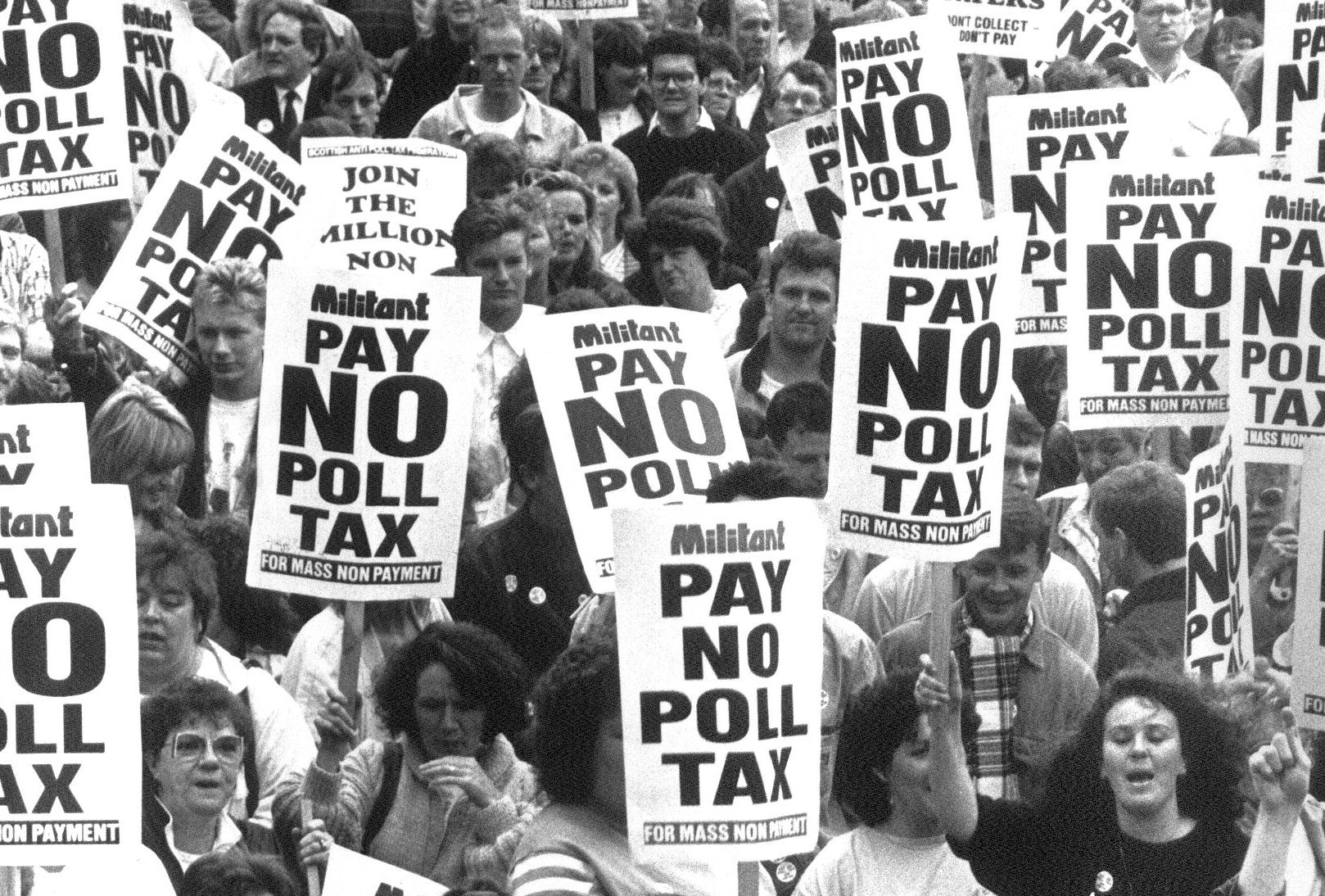

In April 1988, a conference of Militant (now Socialist Party) supporters decided to launch anti-poll tax unions throughout Scotland. An opinion poll, some 12 months before the poll tax was actually introduced there, showed 42% would be in favour of a campaign of illegal non-payment. Amongst Labour voters the figure was 57%.

The anti-poll tax unions mushroomed. In Glasgow three months later, 350 delegates from 105 anti-poll tax groups agreed to set up the Strathclyde Anti-Poll Tax Federation. The confidence of those building the anti-poll tax unions with the strategy of non-payment was well placed. By the end of 1989, one million of the nearly four million adult population in Scotland had refused or delayed payment.

Don’t pay, don’t collect

The poll tax was made unworkable by grafting together the millions unable to pay with millions more unwilling to pay. ‘Don’t pay, don’t collect’ was the slogan from the beginning of the campaign. And the strategy of mass non-payment and non-collection was campaigned for, almost singularly, by the anti-poll tax federations in Scotland, and later in England and Wales, following the lead given by the Militant.

Many supported non-registration as a way of ‘hiding’ from the tax, and it did remove a million or more from the electoral register. But it was only useful as a precursor of preparation for non-payment, not a viable strategy in its own right.

Then as now, with battles against local council service cuts, Labour leaders restricted their opposition to parliamentary speeches. Those involved in, and especially leading, the anti-poll tax movement understood that major social issues are not resolved in parliament – where no matter how good the speeches, governments rarely listen – but outside, by real social forces.

Should we break the law?

The Labour leaders opposed any strategy which involved refusing to obey the law. But there are two types of law – those we all accept that keep society in check (laws giving pedestrians right of way on a zebra crossing, through to laws against murder) and naked class laws, such as the restriction of union rights to organise industrial action – or taxes, like the poll tax, blatantly designed to benefit the rich at the expense of the rest.

If preceding generations hadn’t had the courage to break laws that declared trade unions illegal, we wouldn’t have many of the gains trade unions have subsequently won for us. We had no qualms about building mass resistance to the poll tax, even if that meant breaking the law.

Many on the left also thought the strategy of illegal mass non-payment could not succeed. The Socialist Workers Party leader, Tony Cliff, dismissed the tactic in a speech at Newcastle Polytechnic in May 1989, saying: “Not paying the poll tax is like getting on a bus and not paying your fare; all that will happen is you’ll get thrown off”!

Those of us already fully involved in preparing the anti-poll tax struggle had more confidence in working people. And, as it turned out, not just in areas traditionally thought of as working-class. As one newspaper correspondent later commented: “I knew Margaret Thatcher was done for when I read that, according to official figures, one-third of the people in Tunbridge Wells aren’t paying”!

Campaign in England and Wales

The campaign against the poll tax in England started small. Some felt Margaret Thatcher couldn’t be beaten – she’d beaten Argentina in the Falklands war and defeated the miners, so how could we win over a tax?

In Coventry the campaign started, like in many other towns and cities, as we gathered outside the Council House and ceremoniously and defiantly burnt the registration forms in dustbins.

MP and Miltant supporter Terry Fields and myself regularly raised the issue throughout 1989 in the House of Commons in speeches and in questions, linked to dozens of meetings we were speaking at out of hundreds that were organised nationally.

At the Labour Party conference in October 1989, a dramatic incident was seen by millions on TV news bulletins. Christine McVicar, a delegate from Glasgow Shettleston Labour Party, tore up her poll tax payment book at the conference rostrum as she moved a resolution calling for Labour to back the mass campaign of non-payment.

She defiantly declared to the conference: “Without the Tolpuddle trade unionists and the suffragettes breaking the law, we wouldn’t be here at this conference… I’m ripping up my poll tax book not as an individual but as part of a mass campaign of non-payment”.

The following month the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation was founded at a conference of 2,000 delegates. The federation was to play the decisive role in the coming battle. The protest grew as 1990 opened with hundreds, sometimes thousands, gathered outside town halls to protest.

The poll tax ‘riots’

Mass demonstrations were organised on 31 March, 1990, the day before 35 million adults were due to get their bills. 200,000 demonstrated in London and a further 40,000 in Glasgow. The divorce between the vibrant campaign organised from below, and the passive opposition of trade union and Labour leaders organised from above, was sharply illustrated a few days later when on 4 April the Trade Union Congress held a rally against the poll tax in a hall that would hold 3,000, but only 800 (mainly union officials) turned up.

The march in Glasgow was entirely peaceful, but the activities and strategy of the police in London led to violent clashes between them and some protesters which the media played up as riots. But that didn’t dent the anti-Tory mood across the country.

At the beginning of April, a few days after the so-called poll tax riots of Trafalgar Square, Labour had an opinion poll lead of 23%! But Labour’s leader, Neil Kinnock, then spent much of his time over the next months and years expelling the leaders of the poll tax rebellion, and ended up squandering that lead. By December, it was the Tories who were ahead by 8% and Neil Kinnock lost the subsequent general election in 1992.

In 1990, the campaign against the poll tax continued to grow. An All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation trade union conference was called in June 1990 and attracted 1,287 delegates from 651 organisations representing 870,000 workers.

The battle moves to the courts

As well as on the streets, in marches, demonstrations and lobbies, the struggle moved crucially to the courts. Two weeks after the date that the first poll tax payment fell due, if it wasn’t received, local councils were legally entitled to begin court proceedings, obtaining ‘liability orders’ calling in the whole year’s debt. If no payment was then received, councils could invoke more draconian enforcement.

By June and July, court cases from liability orders were in their hundreds of thousands, and the millions who did not pay ground down the judicial system.

Hundreds of activists developed the skills of an obscure court role, the ‘McKenzie friend’. As thousands were summoned to the courts, facing the magistrates and the council officials without the benefit of legal representation, hundreds and hundreds of ordinary working-class people stepped up to the role, trained by the briefing notes provided by the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation and, in particular, the poll tax Legal Group.

Competitions grew as to who could keep the magistrates busy (or, even, entertained) the longest. So in hundreds of courts, at best, magistrates were hearing a few dozen cases a day. But liability orders were obtained, and more punitive enforcement began.

Bailiffs

After obtaining a liability order, legislation allowed councils to invoke deductions from earnings or certain state benefits. If non-payment persisted, the bailiffs were sent in to seize property for sale (known in Scotland as warrant sales or ‘poindings’).The final sanction was imprisonment for up to three months.

The use of sheriff’s officers (bailiffs in Scotland) began as early as July 1989. One of the first cases was against Jeanette McGinn, a widow from Rutherglen in Glasgow, who had refused to register for the poll tax and not paid the £50 fine. When the sheriff’s officers gave notice they were coming to her home to seize her property, she telephoned the Strathclyde Anti-Poll Tax Federation office, which organised buses and minibuses from all over the city and region to take hundreds of protesters to her home.

The council backed down. Similar tactics were later used in England and Wales, as local anti-poll tax unions developed ‘bailiff busters’.

Imprisonment

The first to be threatened with jailing in England was 74-year-old Cyril Mundin, in Northampton, in October 1990. Cyril had been a paratrooper on D-Day, so a certain amount of press interest was inevitable.

Hundreds marched to the court in his support. A Sunday newspaper, the News of the World, sent ‘Captain Cash’ to pay the fine, so that Cyril wasn’t sent to prison! But Rupert Murdoch’s paper couldn’t (and wouldn’t) pay all the outstanding poll tax bills! And so the jailings began. Pensioners were sent to three-month maximum security prisons such as Durham. In the first 18 months, 117 people were imprisoned by 40 councils. At least ten pensioners received sentences totalling 366 days.

Every jailing was challenged in the High Court by judicial review, whereby a senior judge was asked to review the procedures by which the imprisonment decision was arrived at. Many cases were won and dozens were released.

Labour’s reaction

Initially, 30 Labour MPs signed their refusal to pay, which would have meant their imprisonment. Only one, in fact, went the whole distance – Liverpool Broadgreen MP Terry Fields, who was imprisoned in July 1991 and served 58 days in Walton prison in Liverpool. Thousands demonstrated outside.

The Labour leadership was vicious. Neil Kinnock condemned advocates of organised mass non-payment of the poll tax as “toytown revolutionaries”. At the next national executive committee of the Labour Party following Terry’s release from prison, Roy Hattersley and Clare Short proposed Terry’s and my expulsion – Terry for going to prison, and ‘bringing the Labour Party into disrepute’, and me for being next in line. Labour later closed down the Labour Party Young Socialists for its role in supporting the campaign. The motion at the October 1993 Labour Party conference was moved by one Tom Watson!

The poll tax is defeated

Eight months after the poll tax was introduced in England and Wales, in November 1990, Margaret Thatcher was forced to resign and John Major replaced her. We had not only moved the government on policy, we’d removed a prime minister!

The poll tax was abolished on 21 March 1991, one week short of one year! Though legal proceedings against non-payers continued for many months and years.

What were some of the lessons learned? Well perhaps the most important was, struggle works! As the late, lamented Bob Crow, leader of the transport union RMT, famously said: “If you fight you won’t always win. But if you don’t fight you will always lose”. And in the case of the poll tax the struggle of those unable to pay united with those unwilling to pay, welded with a confident strategy and tactics, led to an historic victory.

It was an organised mass struggle, not individuals left to fight or suffer alone, that made the battle against the poll tax so seminal in the 20th century. We could have won more quickly had the trade unions had a policy of non-implementation, which we had called for since 1987 with the slogan “don’t pay, don’t collect”.

But we did win, and it was because Margaret Thatcher and the political establishment in Britain made two fundamental mistakes. Instead of their previous tactics of taking on one section of the Labour movement at a time in separate struggles, they introduced a tax that attacked the whole of the working class at the same time, making solidarity even easier to achieve. And they mistook the timid leadership of the Labour Party and trade unions for the determination of the working class once roused in struggle.

It’s one thing to make laws, another to implement them – a lesson the establishment doesn’t want working-class people to remember. It also illustrates what Marxists have often argued: that general election results are merely snapshots of the mood of the country on a particular day, not set in stone for a whole parliamentary term.

Even large government majorities can be ephemeral when working people are roused in anger and have organisations with a leadership determined to resist injustice – a point worth remembering even now with Boris Johnson’s 80-seat Tory majority, the largest since Margaret Thatcher’s in 1987.

Better to break the law than break the poor

- Imprisoned poll tax fighters meant business

Eric Segal is a member of the Socialist Party and secretary of the South East Kent Trade Union Council. He was a leading activist in the Kent Anti-Poll Tax Federation. and was jailed for 30 days in 1991 for non-payment of the poll tax.

The anti-poll tax struggle provided incontrovertible evidence that the state in Britain is not some benevolent, impartial institution. The role the courts played in legitimising and then enforcing the poll tax legislation cut through the illusion that fairness and reasonableness uphold the rule of law.

What more evidence do you need when you look at the part the police played in backing up the bailiffs who were sent by the courts to force their way into homes to take the possessions of working-class people? Or the way they policed the anti-poll tax demonstrations or jailed those who, in the words of MP Terry Fields, would rather break the law than break the poor?

The battle against the poll tax showed that the state is used as a vehicle to maintain and defend the dominant interests of the capitalist class – contrary to the view held by academics and the reformist right wing of the labour and trade union movement.

Prison is a part of the state machinery. Imprisonment for political activity is not new, and prison has long been known to be the university of revolutionaries. We understood that it was likely that, alongside those who simply could not pay the poll tax, the jailing of anti-poll tax campaigners would be part of the mass campaign to stop the tax. We knew that the Tory government would not hesitate to use all the resources to defend its class.

The election to a position in the Kent Anti-Poll Tax Federation was conditional on the understanding that it could result in imprisonment for non-payment. We had to show that we were deadly serious in our determination to break this unfair tax and bring down Thatcher. In other words, we meant business.

Our slogan, ‘pay no poll tax’, showed the clear difference between us and the leaders of the trade unions and Labour Party in our determination to break the tax. The key was that this was a mass movement led and organised by the working class with a clear perspective.

It was not the demonstrations alone that won or the ‘riots’ that took place when the police attacked peaceful demonstrators in Trafalgar Square. It was the sustained and organised campaign of civil disobedience, the mass non-payment campaign proposed and initiated by Militant supporters. At its height, 18 million people were defying the law and refusing to pay. It was the organisation of that movement and clear ongoing tactics and strategy that succeeded.

Those of us in the leadership of the anti-poll tax unions who were prepared to go to jail did so in the knowledge that we were supported by our class. We were not individuals looking for martyrdom, but we were prepared to take the fight into the belly of the institutions of the state.