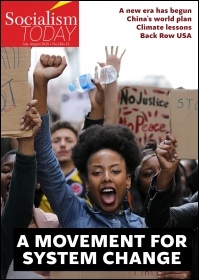

The cover article from the July-August edition of Socialism Today, No. 240.

A new movement for system change

Malcolm X famously said, ‘you can’t have capitalism without racism’. Assessing the new upsurge in the #Black Lives Matter movement, Hannah Sell argues that fighting racism does mean a fight to replace capitalism with a new society, socialism.

The brutal police murder of George Floyd has ignited a massive #Black Lives Matter movement, first in the US and now globally. This is not the first global wave of demonstrations in recent years – #BLM first spread worldwide in 2014, as did the women’s marches after Trump’s election. We have also seen a huge global wave of protests on climate change.

The current movement, however, has important characteristics that mark it out as being on a different level than what came before. It has a broader reach. The Washington Post, for example, reports that there have been far more demonstrations in the US than the previously unprecedented 650 women’s marches that took place in 2016. In addition to the big cities, protests have taken place in even the smallest towns, including in places in the south with recent histories of white supremacist activity.

As Rana Foroohar put it in the Financial Times, protests are happening in “some overwhelmingly white communities – places like Boise, Idaho and Colorado – as well as multicultural cities like New York” and that many of the issues taken up by the movement impact on the whole working class, “including increased spending on education and social safety nets”. She concludes that the protests are about “both race and class”. They are overwhelmingly made up of working class youth, with young black people being joined by whites, Asians and Hispanics in a multi-ethnic and multi-racial outpouring of rage. The protests continued in the face of brutal police repression, including more than 10,000 being arrested. They have widespread popular support. According to one Washington Post poll an overwhelming 74% of Americans support the movement.

The picture is similar globally, with major demonstrations in numerous countries. In Britain, for example, the centres of every major city and many smaller towns have been flooded by young people from working-class estates determined to make their voices heard. The police killings of George Floyd and countless other black Americans, along with the crude racism of Trump, were the triggers, but the movement – in the US and internationally – has a broader scope.

The immediate kindling for the explosion taking place are the effects of the coronavirus crisis, which has laid bare the rotten character of twenty-first century capitalism, including its deeply engrained racism. The BAME populations in both the US and Britain have been more likely to die from the virus, in large part because they are overwhelmingly in the poorer sections of the working class – having to keep working through the pandemic and often living in overcrowded conditions. At the same time the huge increase in unemployment has seen one in six black workers in the US lose their jobs. George Floyd himself both caught Covid-19 and lost his job due to the lockdown before he was killed by the police.

The pandemic did not come after a period of prosperity but rather the years of belt-tightening and austerity that followed the 2007-08 world economic crisis. The predominantly young people taking part in the movement have spent all their conscious lives in an era when the inability of capitalism to meet their aspirations has been abundantly clear. Their parents have suffered the longest period of wage restraint since the 1930s, and their own future was already one of low paid, insecure jobs before the emergence of coronavirus and the devastating economic crisis it has triggered. The accumulated anger at all of this lies behind the grand scale of the protests.

Right-wing governments and leaders whipping up racism – above all Trump – is clearly a factor but the movement is not under the illusion that merely electing less reactionary politicians will solve the problems. After all, in 2016, two years after #BLM burst onto the scene, and the final year in office of Barack Obama – the first black US president – there were still over 1,000 police killings, with black men nine times likelier to be killed than other Americans. Poverty among black workers increased while Obama was in power. Between 2007 and 2016, with Obama in office for most of that time, the average wealth of the bottom 99% of Americans dropped by $4,500, with African Americans worst affected. Black home ownership plunged, back to the levels of the late 1960s, as mass foreclosures took place. It has not recovered since.

There is a strong deep-felt mood on the current protests therefore, that deep-going fundamental change is needed to end racism – something that has been ingrained in society for centuries and remains so today. In Britain as well as the US an understanding of how deeply rooted racism is, was shown in the mass protest of young Bristolians who felled the statue of the slave trader Edward Colston and chucked it in the docks. It is from those docks that the ships sailed that built Bristol’s wealth on the blood of African men, women and children. Campaigns to remove the statue had been ongoing for decades with no result. In the face of establishment opposition the current black Labour mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees, had not dared to even add a plaque acknowledging the estimated 19,000 Africans who died in Colston’s ships. The youth of Bristol had the courage that he lacked. A statue is only a symbol, however, and what is posed now is what is necessary to achieve societal change.

Capitalism and racism

At this stage the movement has no clear organisation or leadership. Regardless of how long this specific wave of protests lasts, it nonetheless represents the beginning of a new phase of struggle, within which participants will debate how to achieve their goals. Some of the issues up for discussion include what role – if any – non-black participants in the movement can play; whether protests can remain peaceful as the state forces respond; how the movement should be organised and whether the struggle against racism is or should be political; and – connected to all the other questions – does fighting racism mean fighting capitalism because, as Malcolm X famously put it, “you can’t have capitalism without racism”. For the many participants in the movement that agree with him, the question of how to end capitalism and what to replace it with is also posed. Even The Guardian’s photo gallery of the protests commented in the captions, “socialism vs capitalism” was “an ever-present conflict” in the protests. At this stage it would be more accurate to say it is a point of discussion among the protestors.

To the establishment media reporting on the protests it must seem strange, and frightening, that opposition to capitalism is an important strand in the movement. After all, many major corporations are going out of their way to show their support for #BLM. In a particularly British example, PG Tips and Yorkshire Tea were involved in a twitter contest to demonstrate their complete opposition to racists drinking their tea! In the US Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon and richest man in the world, is one of many who has declared his solidarity with the #BLM protests. The corporate rush to identify with #BLM is significant, because it reflects the popular support for the movement. Nonetheless, regardless of the intentions of individual capitalists – cynical or otherwise – capitalism remains an intrinsically racist system.

Karl Marx, the founder of scientific socialism, described how capitalism came into being “dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt”. He was talking primarily about the horror of the transatlantic slave trade, which was crucial to the development of capitalism. The statue of Edward Colston is one of countless representations of its role in the development of British capitalism. Capitalist politicians from all parties – including the new Labour Party leader Sir Keir Starmer – expressed their horror that Bristolians ‘took the law into their own hands’. Yet a poll in the local paper – the Bristol Post – showed that 61% of the population supported the demonstrators. And of course, when, for example, statues of Lenin were pulled down during the restoration of capitalism in Russia, they described it as a heroic and democratic act. Only when it is statues that are connected to the authority of British capitalism does it become ‘anarchy’ and ‘lawlessness’. And while they have generally condemned the Bristol demonstrators, institutions up and down the country have also rushed to be seen to act to remove at least some of the most blatant examples of – literally – putting slave traders on a pedestal.

Rooted in the capitalist nation state

Tearing down statues can only have a symbolic effect, and is not a central demand of the movement, but has mainly been used by the government and right-wing press as a distraction from the central issues. However, there is a limit to how far the British ruling class is prepared to go even on symbolism. Slavery played such a central role in creating the basis for British capitalism that those involved can never be cut out of the supposedly ‘glorious history’ that is an essential bulwark of support for their system. Virtually every institution of modern British capitalism that existed during the years of the transatlantic slave trade was deeply involved in it. The Royal Family, the Church of England, and many of Britain’s still-existing banks – including Barclays, Lloyds and HSBC – are among those who profited from the slave trade.

Capitalism is a global system but it remains based on nation states. The first countries in which capitalism developed were in Europe, followed by the US, and they have continued to dominate and exploit the rest of the globe. Every national capitalist class relies on a historically cultivated but now deeply ingrained national consciousness to maintain its social base, which includes a version of history which suits its needs. The erection of the Colston statue 170 years after his death, as part of creating a historical narrative to justify imperialism, is one small example of this. In Britain and the other imperialist countries, racism is deeply imbedded into both actual history and the accompanying national mythology.

With slavery came the development of a huge edifice of racist ideology designed to justify what was being done. Later that ideology was adapted to justify the imperialist plunder of Africa, Asia and Latin America. Protestors have rightly pointed to the racism of Winston Churchill. His innumerable racist comments were part and parcel of his justification of British imperialism as being good for what he described as ‘primitive’ and ‘subject races’. However, his views were nothing exceptional, but ingrained in the British ruling class.

US capitalism has a different, but no less racist, history. The US civil war developed between the rapidly developing industrial capitalists of the North and eleven Southern states based on the slave-owning plantations. Initially the US president Abraham Lincoln had no intention of declaring the end of slavery, but was forced to do so after the North suffered a series of defeats in the first period of the conflict. The 1862 proclamation of emancipation had an immediate effect on the course of the war as hundreds of thousands of slaves left the plantations, weakening the Southern economy. Most went on to fight for the North, seizing land from the plantation owners as they did.

The period immediately after the civil war was known as the ‘reconstruction’. Poor whites and blacks fought together in a mass social movement for the right to vote, for publicly-funded education and for land, summed up in their slogan ‘forty acres and a mule’. The Northern capitalists backed the movement up to a point in order to consolidate their victory over the Southern plantation owners. However, as soon as they were confident of their power, they moved to curb the dangerous encroachment on the rights of property that the unity of the former slaves and poor whites represented. The Ku Klux Klan was unleashed to carry out a reign of terror on black people, as well as poor whites. The formal rights won were diluted by the Jim Crow laws while ‘lynch law’ enforced the reality of no rights for black people. US capitalism therefore developed with a large black population making up a significant minority of the rural poor and working class, suffering vicious institutional racism.

Today, the ruling class of the advanced capitalist countries have had to adapt in the face of mass movements against racism and imperialism. Direct colonial rule is mainly a thing of the past. The crude overt racism of the past is less acceptable in society as a whole. Nonetheless, racism remains a vital part of how capitalism maintains its social base.

The role of racism

Two hundred and fifty years ago the gap between the richest and poorest nation states was around five to one. Today it is 400 to one. Racism is used to justify the exploitation of the human and material resources of the rest of the world, for example, by putting the continued impoverishment of the peoples of Africa down to some imagined innate failing leading to corruption and governmental incompetence, rather than capitalism’s inability to develop Africa which is endlessly bled dry by the imperialist countries. More than a billion people live on the continent of Africa, yet the GDP of the whole of sub-Saharan Africa is a fifth of US GDP. Most of the participants in the #BLM protests are focussed on fighting racism where they live, but the question of ending imperialist exploitation of the neo-colonial world is also motivating them.

Racism is also a vital means to divide the working class – who make up the overwhelming majority of society in both Britain and the US – against each other within countries. Over recent decades real wages have at best stagnated and often decreased, while the profits of the capitalist class have increased dramatically. The capitalists always use any means they can to divert attention from their responsibility for low wages – variously blaming women, young people, or agency workers for driving down pay. Racism – through laying the blame on migrant workers whilst simultaneously justifying paying them below the going rate – is currently their most effective means of divide and rule. Just 8% of the 1,084 directors of the hundred biggest companies on the London Stock Exchange are from BAME backgrounds. Even if the number was far greater, however, this would not alter the capitalists’ need to divide in order to rule. Individual capitalists may proclaim their support for #BLM, but they are still benefiting from racism as a means to preserve the rule of their class and the system of exploitation of the majority by a tiny minority that it rests on.

At the same time it is not accidental that we have seen the election of right-wing populists like Donald Trump, the Brazilian president Jair Bolsanaro, and to some extent Boris Johnson, who use crude racism in a way that unsettles some other sections of the capitalist class. Defending an increasingly unpopular system, capitalist politicians have to find some way to secure a social base. Whipping up division is one of their only options and will remain so. Even those sections of the capitalist class who object would generally far rather have a capitalist right-wing populist than a left figure in government, particularly if their election might give the working class confidence to fight. Look at the flood of big-business donations to the Tories in the run up to the 2019 general election, 26 times the amount received (mainly from the trade unions) by Labour. Despite their opposition to Johnson, the Financial Times – the paper that comes closest to representing the views of Britain’s capitalist class – reluctantly called for a vote for the Tories because the alternative of a Jeremy Corbyn-led government was far worse from their point of view.

This does not mean that it is impossible to win victories under capitalism in the fight against racism. As with previous mass struggles, the current movement has already won some concessions. Considerable legal improvements and steps forward in social attitudes can and have been achieved under capitalism. So can a further development of a black elite, which has been a conscious policy of the ruling class in the US since the civil rights movement, in order to increase the stability of their system by giving African Americans a ‘stake’ in the American dream. There is no prospect, however, of ending racism under capitalism. As the system enters crisis, even some of the gains of the small black middle and upper-middle class will be undone. In the US between February and April 3.3 million businesses – 22% – went bust. Among black business owners the decline was 41%. Without doubt some of those who had clawed their way up the social ladder are going to be thrust back into the ranks of the urban poor.

Debates in the movement

Ending racism then does require ending capitalism. The answers to the other questions being debated in the movement flow from this conclusion. Many of the issues now being considered were debated in previous struggles. During the US civil rights movement a generation of heroic African Americans learnt vital lessons on the basis of experience. The early stages of the movement – epitomised by Martin Luther King Jr – put the emphasis on pressurising the institutions of capitalist society, and particularly the Democratic Party establishment, for legal advancements. The failure of this approach to achieve fundamental change led to many, including King himself, to look for other alternatives. At the time he was killed, in April 1968, he was looking towards working class struggle as a way forward.

King’s assassination sparked a wave of riots across the US. A mood of opposition to rioting or any violence is dominant in the current movement. Demonstrations have remained largely peaceful in the face of large-scale police violence, particularly in the US. In Britain the response to threats from the far right was to cancel the main protests in London. Some of the small number of BLM protestors who still attended pointedly demonstrated their peaceful intentions by risking their own safety to rescue a far-right protestor from being trampled in the melee.

In the future, however, faced with further state violence, riots could develop. This would not represent a road to victory, on the contrary it would make it easier for the capitalist class to undermine popular support for the movement, imprison its most determined fighters, and lead to the destruction of facilities used by the black and working class communities the movement aims to defend.

However, that does not mean taking a passive approach when faced with the prospect of brutal police and sometimes far-right violence. The need for organised self-defence was a conclusion drawn by later leaders of the civil rights movement, including Malcolm X and the Black Panthers. Organised stewarding to protect demonstrations has already started to develop from below in the current movement but to do it fully and effectively requires mass democratic organisation.

For both Malcolm X and the Black Panthers the struggle for organisation was linked to a search for what programme was necessary to win black liberation. Malcolm X came to see that ‘you can’t have capitalism without racism’. He had no illusions in the capitalist Democratic Party offering a way forward, comparing the liberal Democrat fox to the Republican wolf who are both as likely to eat you. Inspired by the movements for national liberation in the colonial world he also came to see the struggle as not simply black versus white but oppressors versus oppressed. Malcolm X was killed in February 1965 and the Black Panthers were founded the following year. In many senses they began where he had finished, representing the high point of the heroic civil rights movement.

The Black Panthers began in Oakland, California and spread like wildfire across the US. At their peak they were selling 125,000 copies of their paper a week. They were founded with the magnificent statement: “We do not fight racism with racism. We fight racism with solidarity. We do not fight exploitative capitalism with black capitalism. We fight capitalism with basic socialism. And we do not fight imperialism with more imperialism. We fight imperialism with proletarian internationalism”.

The Panthers did not have the opportunity to fully develop, never mind implement, their ideas. Faced with massive state repression, with many of their leaders gunned down by the police, they went into decline quite rapidly. Nonetheless, it is no surprise that they are a major inspiration for the young generation currently taking to the streets. The approach they were moving towards represents the road to victory in the 2020s.

The austerity generation

The Black Panthers recognised that the alternative to capitalism was ‘basic socialism’. They saw that what was needed was to take power and control from the tiny handful of capitalists who own the major industries and banks. This was necessary so that the resources could be harnessed to begin to build a society able to meet their demands for jobs, decent housing, education, peace and more.

Having grown up in the era of capitalist austerity, many of the young people now taking to the streets had already drawn anti-capitalist conclusions and begun to look to socialism as an alternative. In the 2019 general election Jeremy Corbyn’s left programme won the support of the absolute majority of young and BAME voters. Overall 62% of 18-24 year olds and 64% of BAME voters supported Labour under Corbyn. Interestingly, whereas the Labour vote dropped overall amongst the poorest sections of the working class, that did not apply among the young, with 64% of ‘DE’ 18-24 year olds voting Labour. Following Corbyn’s replacement with the pro-capitalist Keir Starmer as Labour leader, a scepticism towards all political parties has grown among some layers. This is inevitable given the miserable diet now on offer from all the mass parties.

However, the most far-thinking sections of young people are weighing up how to achieve their goals against the background of growing mass unemployment and economic crisis. This poses the question of the need for a mass political voice. The Corbyn experience has shown that socialism cannot be achieved by one left leader at the top of a party which is still dominated by capitalist politicians. The defeat of Bernie Sanders within the capitalist Democratic Party – and his subsequent backing for Joe Biden in the November presidential election rather than standing independently himself – will lead to similar conclusions being drawn in the US. The need for a mass party of the working class which acts as a voice for mass struggles is a concept which will be seized by the generation currently moving into action on a much greater scale than in recent decades.

The heroic Black Panthers did not, of course, attempt to build a party of the whole working class. The Panthers were consciously a black party. They stood, however, for a united struggle of all sections of the working class, understanding that this was necessary to overthrow capitalism. As founder Bobby Seale explained it, “those who want to obscure the struggle with ethnic differences are the ones who are aiding and maintaining the exploitation of the masses. We need unity to defeat the boss class – every strike shows that. Every workers’ organisation’s banner declares: ‘Unity is strength'”.

This is in complete contrast to those proponents of identity politics today who see things only in terms of racial identity and dismiss all white workers as ‘privileged’. These ultimately reactionary ideas are of course present in the current movement and, given the absence of mass democratic organisation, individuals who support them can attempt to assert their leadership. This approach does not reflect the views of the majority of participants however, who can see both that #BLM is receiving wholehearted and active support from many white working class youth, but also that many of the issues on which they want to see change – including poverty, low pay, joblessness and housing – affect the whole of the working class.

The potential for united struggle

The civil rights movement took place against the backdrop of the long post-war boom. Today, far more than then, the possibility for a mass united struggle of black and white workers on these issues is posed. One factor in this is the greater anti-racist conscious of big sections of the working class, but most important is the growing crisis of capitalism which is threatening the future of all working class young people. As it develops, even some sections of white workers who have currently swallowed the capitalist lies that it is BAME workers rather than capitalism that are responsible for their misery, can potentially be won to an anti-racist mass united struggle against capitalism.

That is not to give an inch, of course, to the idea that the #BLM movement should wait for other sections of the working class to ‘catch up’ before it acts. No oppressed grouping ever won its demands that way! The mass protests over recent weeks have already achieved more than endless patient lobbying. It does point, however, to the need to link the fight against racism to the vital economic questions of jobs, homes and public services. This approach does not exclude the possibility that – like the Panthers – there may be attempts at building specifically black political organisations. If they are, as the Panthers were, a step towards linking the struggle for black liberation to the struggle for socialism, such parties could be a step forward.

However, particularly in Britain, there is the potential for more generalised struggle to mean that a mass party of the working class is posed in the next period, rather than sectional formations. Even if the latter develop they are likely to be transitory, quickly looking towards uniting with other sections of the class. The need for a new mass party to have a federal approach, with different socialist and workers’ organisations coming together in common struggle whilst having the right to maintain their own identity and programme, could play an important role in this process.

Even during the coronavirus crisis we have seen a glimpse of the potential power of the working class. Trade union membership has surged as workers have looked to a collective means to defend their health, safety and pay. Very multi-racial groups of workers – such as the London bus drivers – have taken militant united action over health and safety issues.

Nonetheless, many of the participants in the BLM protests will not be aware of the potential role of the 6.4 million strong trade union movement in fighting for the rights of black and Asian workers. The responsibility for that lies entirely with the many trade union leaders who have paid lip service to supporting #BLM while failing, or in some cases refusing, to mobilise for the demonstrations on grounds of the lockdown.

The Socialist Party has been to the fore in fighting to mobilise the workers’ movement in support of #BLM. Looking back on the Panthers experience one of its founders, Huey P Newton, commented that their attempts to work together with ‘white radicals’ failed because the white radicals did not have a base in the working class. The important working class base our party has started to build stands us in good stead for winning the new generation now entering struggle to socialism.

Objective developments will, however, play the decisive role. The recent growth in trade union membership has taken place despite the inadequacy of the leadership of the TUC because workers see they need to be in a trade union to defend their interests. Facing a worse economic crisis than 2008, mass unemployment, increased homelessness, and savage cuts to already decimated council services, multiple struggles will develop, many involving the same young people currently on the streets. When faced with a choice in elections of different parties who all refuse to support those movements, the need to fight for working class interests at the ballot box will be clearly posed.

The Socialist Party will support all steps towards independent working class political representation. One important role of a mass workers’ party would be to provide a forum for discussion about how to organise the struggle and beyond that on how to transform society in the interests of the majority. The conclusions drawn by the Socialist Party – that it is necessary not just to reform capitalism but to overthrow it, bringing the major corporations and banks into democratic public ownership under workers’ control and management – are not yet the view of the majority. Nonetheless, the defeat of Corbynism has already led many of the new generation to reject ‘tinkering around the edges’ and to search for a means to achieve fundamental change. That will be driven home by coming events.

We are at the start of a decade of enormous capitalist crisis and turmoil. The current movement is the first wave of the radicalisation that will result. Many of its participants can be won to the struggle for socialism and have the potential to stand on the shoulders of giants and to achieve what their heroes, the Black Panthers and Malcolm X, attempted – the socialist transformation of society, laying the basis for the elimination of racism.