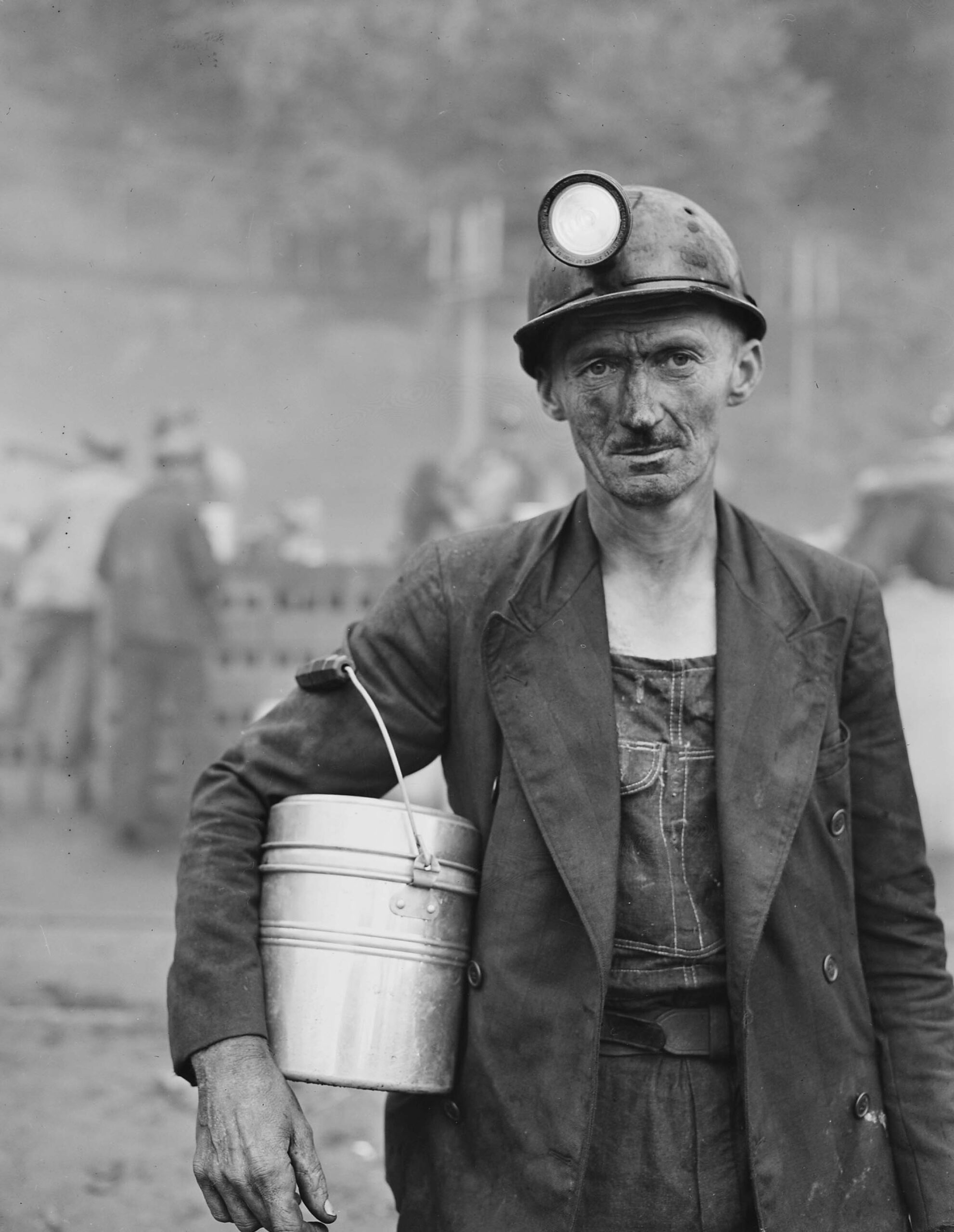

Orwell joined a shift at a coal mine and wrote about the terrible working conditions of miners, photo Russell Martin/CC (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

Domenico Hill, Bristol south Socialist Party

In early 1936, a then unknown George Orwell was commissioned by the publisher Victor Gollancz to travel to the north of England to research ‘the conditions of the working class’. ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’ was published in 1937, after Orwell had travelled to Spain in December 1936 to fight fascism, as part of the Poum (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unity).

The book is not only a great insight into the actual conditions workers faced during the depression of the 1930s, but also sheds light on the political journey of Orwell himself. He progresses from lower-middle-class Eton boy and colonial police officer, through unstable employment and poverty, towards growing socialist convictions.

Orwell stayed at a boarding house in Wigan and noted that, far from being wealthy and detached, many landlords barely made a living, sharing the rationed portions given to their lodgers, desperate to get the income provided from travelling salesmen, while bitterly resenting their lodgers.

Coalmining

He managed to join a shift at a local coal mine and was exhausted within minutes just getting to the coalface, which not unfrequently was over a mile on foot from the main shaft. Orwell, a tall man, describes an agonising walk through a low tunnel, constantly doubled over and crawling on his hands and knees. On arriving at the coalface, the miners had to lie or kneel down and hack away at the coal with their pickaxes.

For anyone who has read Zola’s novel ‘Germinal’ about French miners in the 1860s (see ‘Books that inspired me: Germinal’ at socialistparty.org.uk), it’s glaring that conditions had changed very little, except that now there was a mechanised conveyer belt which took away the coal rather than ponies.

Orwell writes about the housing conditions and income of mining families, particularly of unemployed miners. Unemployment benefits, ‘the dole’, had been introduced in 1920. A debate raged in the press about whether the amount of dole was too little or too much, ‘encouraging idleness’.

Orwell lists a weekly budget for an unemployed miner, his wife, and two small children, based on a means-tested dole of 32 shillings a week – an amount of money barely able to cover a semi-starvation food diet, fuel and rent. The main items are potatoes, flour, meat, coal, sugar and tea. Only a small percentage of expenditure goes on vegetables. Milk for the infant is donated by a charity. Rent makes up 9 shillings.

An outraged citizen wrote to the News of the World and the New Statesman claiming it was perfectly possible to eat healthily for a week with 3 shillings and 11 pence. Among the food items listed by this gentleman are: three wholemeal loaves, 1lb carrots, 2lb dates, 1lb onions, 1/2 lb margarine and ten oranges. The list excludes rent, fuel, clothing, repairs, travel, and the budget is for just one person.

At that time, many middle-class people raged against workers who ‘didn’t eat properly and couldn’t cook’. A particular source of ire was the perceived indulgence of workers for massive amounts of tea, sugar and cigarettes. In the case of the unemployed miner, tea and sugar cost 2 shillings and 9 pence a week, out of 32 shillings. If only the workers would get educated and eat more oranges!

Now in the 21st century, unemployment benefits continue to mean semi-starvation for thousands. While, parliament debates clawing back £20 a week from Universal Credit, food has to be distributed by ever-expanding foodbanks. The capitalist press continues to push lies about workers spending food vouchers on cigarettes and alcohol, leading to their replacement with meagre food parcels for school children who qualify for free school meals.

Housing

In the 1930s many workers lived in houses which were subsiding and damp, with walls bulging out and frequently blocking doors and windows. The design of many of the terraces was such that not only did people have to go outside to go to the toilet, but they had to go out the front door and walk down the end of the street to join a queue at the back.

Orwell mentions the new ‘corporation’ (council) estates being built then, which survive in suburbs to this day. No doubt these represented a massive improvement in conditions, with baths, running hot water, and gardens.

But Orwell states how many workers felt resentful and alienated by having to move there, and some preferred to stay in the slums because ‘it’s more homely’. Orwell found that the rents for council houses were usually far higher, workers were moved much further away from their places of work, and complained that the estates were ‘soulless’ and ‘prison-like’.

The Road to Wigan Pier dwells a lot on the attitudes between classes, particularly the dislike and even physical revulsion many middle-class people felt for the working class, disguised by a studious courtesy. The more middle-class people slid into poverty in the 1930s the more tenaciously they held on to their perceived privileges of being ‘gentlemen’.

Much of what Orwell writes about social attitudes and divisions, fostered by the capitalist class, echoes painfully in the current day. This book is a must read to remind us of what we have won, what is being taken away, and how to win a better society in future.