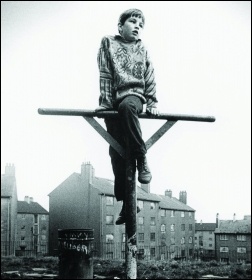

‘An unsentimental depiction of the brutality and inhumanity of capitalism’

Eileen Hunter, Nuneaton Socialist Party

‘Shuggie Bain’, written by Douglas Stuart, is a novel that at times makes the reader stop and reflect. You feel the pain of young Shuggie growing up in Thatcher’s 1980s, a pain felt by working-class communities including in now ex-mining villages like mine.

If you are under 30 and you want to find out how Thatcher’s economic policies affected the working class, especially single parents and men who lost their jobs in heavy industry, then this book will provide an unsentimental depiction of the brutality and inhumanity of capitalism. For those of us who lived through these times and in those communities, we are reminded of the honourable way we fought against this new era of brutal capitalism.

Stuart, like Steinbeck before him in Grapes of Wrath, contrasts capitalism’s inhumanity with the sublime efforts of the characters, such as Shuggie and his mother Agnes, to defy their bleak surroundings and create moments of sheer delight.

Stuart takes us on a grand adventure with Agnes and Shuggie: “Along the pit road in the middle of the night, the peat bogs are pitch-black, and everything is silent but for the low gurgle of burn water and song of bog toads… It all seemed less ominous to her now, less of a sucking black hole meant to keep her stuck.”

We sing Agnes’ happy song, ‘I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden’, as they approach their destination, a roundabout, and we feel Shuggie’s epicurean connection the following morning as he views his front garden: “The transformation of the small plot that was once brown dirt and waist- high grass was a waving ocean of colour. Dozens of healthy, fat flowers waved in the breeze: peach, cream, and scarlet roses, all dancing and bobbing like happy balloons.”

Deindustrialisation

This book is an emotional rollercoaster, such is the life lived by those depicted. Stuart understands that the ‘tough Glaswegian’ stereotype of what it meant to be a man had been shattered with the wholesale closure of the shipyards and the mines. Men became shadows of their former selves. Stuart shows them in the club at the end of Pithead Road, remembering their honourable fight in their titanic struggle to save their pits and communities in the miners’ strike of 1984 -85. Today, many of the miners’ welfare clubs have gone, and the men have nowhere to reminisce or celebrate their lives.

The novel is set in the 1980s when many LGBT+ people came of age during the era of Section 28, a homophobic law passed in 1988 by a Conservative government that stopped councils and schools “promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.”

As Shuggie struggles with why he is bullied and doesn’t act like the other boys, we see him as the others do, in his attempts to try and understand his own sexual identity. Not only were these discussions banned in schools, but Tory Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher said at the time: “Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay. All of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life.”

In The Militant, the Socialist Party’s predecessor, we fought against this intolerance and I remember setting up the first Gay/Straight Alliance with my students in school. We were actively passing motions for all trade unions to rally and protest. This led to mass protests by LGBT+ campaigners, supported by workers as depicted in the film ‘Pride’. Ultimately, the law was stopped in Scotland in 2000 and in the rest of the United Kingdom in 2003.

I particularly liked the way Stuart plays with time in the book. We start at the end in 1992 and transcend into a bedroom in 1982. Here Agnes dreams of dancing and escaping her parents’ high rise flat. Not easy as a single parent with three children.

This book takes us to the Monday post office queue with all the other single parents whose benefits were paid every week on an order book. This at least offered some hope over the weekend. Now, in 2021, those extra allowances, as recognition of your additional financial hardship as a single parent, have been stripped away and replaced with the struggle to get through a month on a flat rate of Universal Credit.

No holds are barred by Stuart in the darkest moments. It’s a rare gift for an author to allow the reader to feel both the sunshine and, as Shuggie and Agnes experience the dark side of family life, the impact of misogyny, sexism and poverty.

As Stuart powerfully demonstrates, Agnes is: “Brought low by the men in her life as she is burnt up by her alcoholism. Those who love her most recoil from the flames. But then, as with Saint Agnes, she rises again in hope, steps out of her own ashes every morning, and tries once more to get sober.”

Shuggy Bain is a Booker prize winner and many reviews look forward to Stuart’s next book. Some want to know what happened to Shuggie after 1992. I’d like to think he turned a corner, saw a Socialist Party campaign stall, bought a paper, and fought back with us, organising to get rid of this rotten capitalist system.

The sign of a great read is that you know when you finish, you will want to read it again. As I walk around my pit village on a midsummer evening, I admire the beautiful blooming barmy roses, and I can’t help but smile as I think of Shuggie and Agnes.

- ‘Shuggy Bain’ by Douglas Stuart, Picador, £8.99