Sascha Stanicic, Sozialische Organisation Solidarität (Sol, CWI in Germany)

The result of the Bundestag elections on 26 September heralds a new political period for Germany. The two big ‘peoples parties’, the social-democrat SPD and Christian-democrat CDU/CSU bloc, have massively declined, winning less than half the votes cast. Back in the 1970s, it was over 90%.

It is almost certain that, for the first time, a coalition of three parliamentary groups will be formed. However, it is also certain that such a new development will not lead to the fundamental change in policy that opinion polls show 40% of the population favour.

The future government will continue to align its policies primarily with the interests of the capitalist class. No matter what coalition is formed, the neoliberal FDP will most likely be the most direct representative of these capitalist interests in the government.

The question of who should pay for the costs of the economic crisis and pandemic control will not be answered in the interests of the workers and socially disadvantaged by either an SPD-Green-FDP coalition or by a CDU/CSU-Green-FDP coalition, as both will operate on the basis of capitalism.

All this makes it even more urgent for trade unions and social movements to prepare for tough defensive struggles.

CDU/CSU in decline

Since 2013, the CDU/CSU bloc has lost seven million votes. The SPD received well over eight million less votes compared to its 1998 peak. Both the right-wing AfD and the left party Die Linke also lost votes.

23.4% of eligible voters did not participate in the election. The ‘party of non-voters’ has become one of the strongest forces.

The next federal government will be weaker than the Merkel governments of the last 16 years, and the ruling class will have increasing difficulty formulating a unified policy.

The CDU’s decline is an expression of the struggles over the orientation of the party and the vacillation between adherence to the Merkel course, which is partly oriented towards ‘social partnership’, for which party leader Laschet stands, and the urging of sections of the capitalist class for harsher attacks on the working class, for which Friedrich Merz stands.

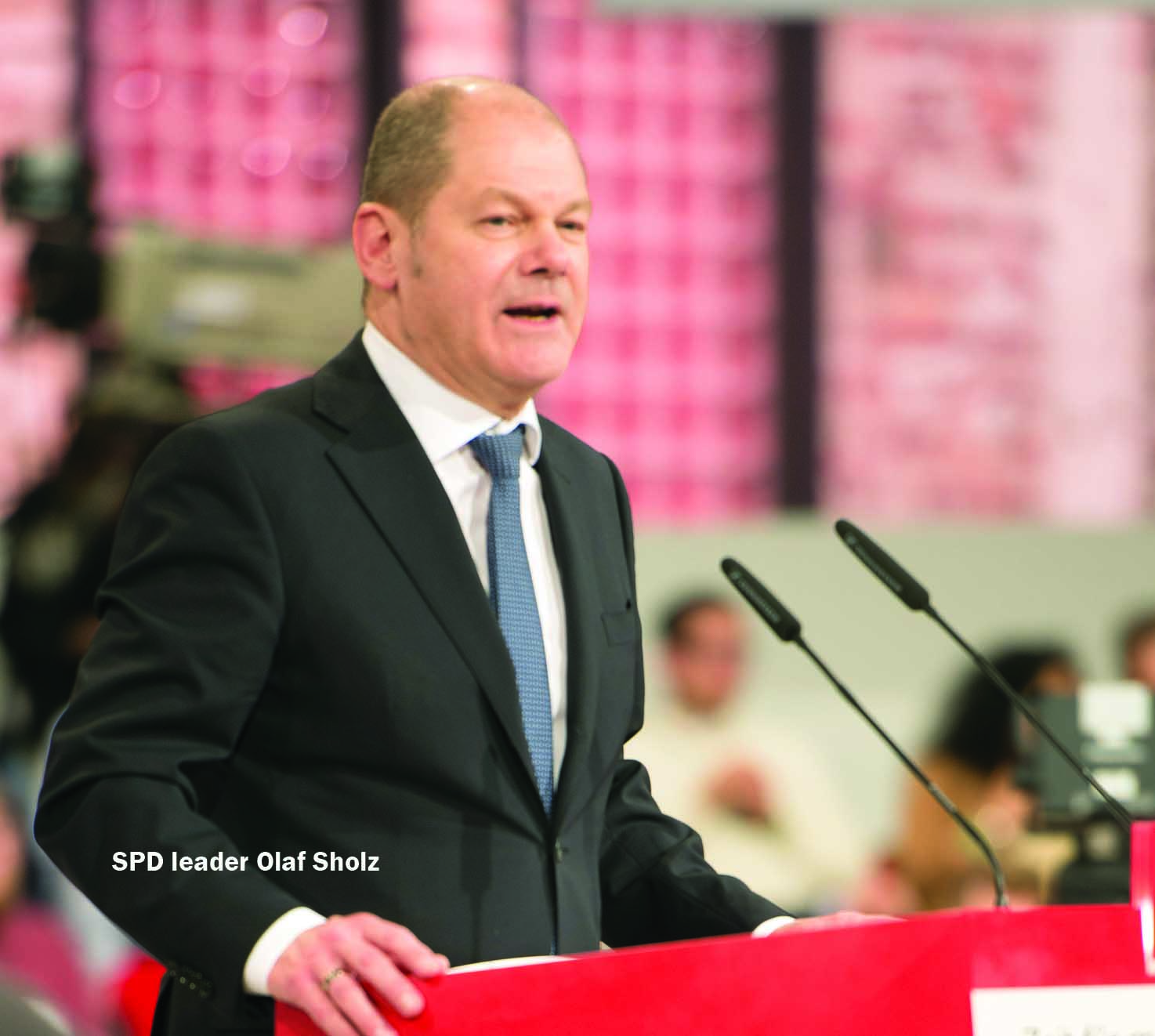

SPD

Even if the SPD is jubilant, it cannot hide the fact that its 25.7% share of the vote is the third-worst result in its history. In recent weeks and months, the SPD benefited from the fact that the CDU/CSU had opted for the ‘wrong’ candidate and that, earlier this year, the establishment media and other capitalist institutions ended the Greens’ soaring poll ratings with a campaign against their top candidate Annalena Baerbock.

This is because they feared the expectations of the population, particularly regarding climate protection measures, that would have arisen with a Green-led federal government. Above all, the SPD did less ‘wrong’ in the election campaign than the others.

The modest increase in votes for the SPD, especially the fact that it was able to mobilise 1.25 million previous non-voters, reflects the fact that social questions played an important role in these elections, and that the Social Democrats have once again blinked to the left with their promises of a €12 minimum wage, the introduction of a wealth tax, and ‘abolition’ of the neoliberal Hartz welfare system, etc.

However, this is not a comeback of the old ‘workers’ party’, but rather an expression of the ‘lesser-evil’ alternative that most voters saw.

Greens and FDP

The FDP and Greens go strengthened into negotiations on a coalition formation – even if the Greens had to bury their Chancellorship ambitions. The fact that the free-market FDP was able to record significant increases in votes is mainly due to the fact that during the pandemic it had succeeded in appearing to some as a ‘reasonable’ critic of the government’s coronavirus policy, and that in the election it focused less on its capital-friendly positions.

AfD

The right-wing AfD has lost votes, but at the same time continued to consolidate itself within the party system. In the eastern federal states of Saxony and Thuringia it became the strongest party, and is still generally twice as strong in east Germany as in the west of the republic.

This will shift the balance of power within the party further in the direction of the right-wing extremist forces around Bj-rn H-cke, and the AfD remains a serious threat to the working class, women, migrants and minorities.

The left

The other loser of the election is Die Linke, the Left party, which has slipped below the 5% voter threshold and will only enter the Bundestag with 30 members because it won three direct constituency mandates in Berlin and Leipzig.

In addition, it is to be expected that a number of left-wing and social movement-oriented MPs will not return to the Bundestag, and thus the political orientation of the parliamentary group may shift to the right.

Die Linke leaders Dietmar Bartsch and Susanne Hennig-Wellsow spoke immediately after the election about ‘mistakes’ that had been made and the need for a reappraisal. But they do not say the obvious: the strategy of pandering to the SPD and the Greens did not work.

On the contrary, as Sol has warned in recent weeks and months, there is much to suggest that many former Die Linke voters preferred to vote SDP and not the Die Linke copy, in order to ensure that the CDU/CSU does not become the strongest force.

That a left-wing party does not gain strength in times of great systemic crises; that it achieves fewer votes than the FDP among workers and cannot mobilise the youth, and that it repeatedly fails to reach non-voters, is an admission of bankruptcy.

Die Linke’s fundamental problems are that it has lost its credibility via its participation in government with the SPD and the Greens; has not stood out from the federal government in the coronavirus crisis, and is considered by many to be the ‘left wing’ of the political establishment.

Above all, this image blocks the way to the millions of non-voters, who apparently no longer feel addressed by any of the existing parties.

In marked contrast to its overall performance, Die Linke in Berlin-Neuk-lln, which has built as an anti-capitalist and social movement-oriented force in the district, was able to achieve significant gains in votes in the election to the city’s House of Representatives, at a time when the party’s overall vote in the city fell.

Die Linke should ruthlessly come to terms with this electoral disaster. It should focus above all on what a left party is needed for: to support and bring together trade union struggles and social movements, arguing for anti-capitalist and socialist perspectives and solutions.

Sol members will continue to work for this in the party. We call on all those who are disappointed by this election result to become even more active now – in trade unions and social movements, in order to counter the policies of the coming government and, with Sol, also in Die Linke in order to advocate a socialist change of course there.

Which government is coming?

One should not rule out any of the mathematically possible coalitions, but there is much to suggest that it will come down to a ‘traffic light’ coalition consisting of the SPD, Greens and FDP, even if FDP leader Lindner would prefer a ‘Jamaica’ coalition with the CDU/CSU and the Greens.

It is also possible that a new government will move in the direction of the current Austrian government model of the conservatives and Greens which gives members of the government extensive freedom in certain departments.

Whether such a government will come about, and if so, how quickly, cannot be predicted at this stage. However, it cannot be ruled out that this will happen much faster than it now appears in view of the confusing and new situation.

- This article can be read in full on socialistworld.net