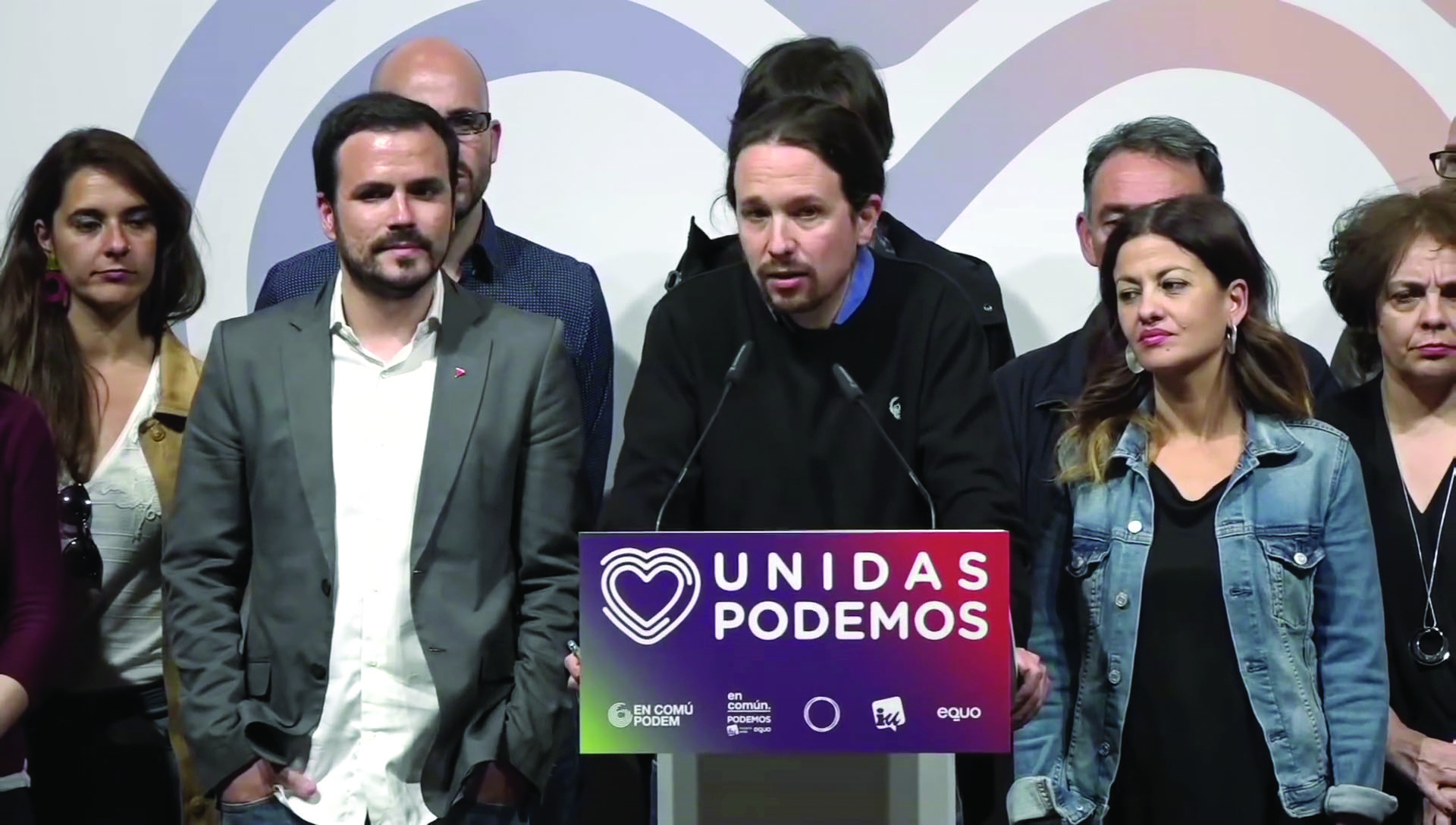

Podemos’s co-founder and former leader Pablo Iglasias. Photo: Podemos/CC

Pablo Iglesias – one of the founders of the Podemos party in the Spanish state and its most prominent representative – announced his resignation from politics earlier this year, the tenth anniversary of the movement of the Indignados (the ‘outraged’) which gave birth to the new party. Ross Saunders – Socialist Party Wales and national committee – looks back over the processes which gave birth to the new party, its development and the mistakes of its leaders which have put its future in jeopardy.

The revolt of the Indignados erupted as a protest against brutal capitalist austerity. The capitalist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and the misnamed Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) demanded that ordinary working-class people pay the bill for the economic crisis, which convulsed the world in 2007-08.

While Spanish banks received huge no-strings-attached bailouts, Zapatero savagely cut back public services, pensions and welfare and held wages down. Jobs were slaughtered and new attacks were launched on trade union rights in order to obstruct the efforts of workers to fight back.

Workers had the power to repel these attacks, but only token resistance to austerity was offered by the conservative leaders of the major trade union federations.

By the beginning of 2011, five million were out of work, including half of all young workers, and evictions were taking place on a mass scale.

With no lead from the organised working class, the anger erupted into spontaneous protests on 15 May 2011 (thereby giving the movement its other name – ’15M’) and raged throughout the summer of that year.

Tens of thousands marched to public squares, like the Puerta del Sol in Madrid, and occupied them. Tent cities grew up and were sustained for weeks in a score of cities.

In protest assemblies, voice after voice was raised against the corrupt capitalist establishment, especially the banks and the existing political parties which submitted to them.

But the anger on display was not focussed by any organisation. Disgust at the role played by former workers’ parties like PSOE and the Communist Party, together with the failure of the tops of the trade unions to give a lead, led to distrust of political parties in general and even suspicion at the idea of organisation.

In the short term, it was the right wing which advanced: the People’s Party (PP), a conservative capitalist party to the right of PSOE, won the council elections held in the midst of the protests and would go on to win the general election later that year.

Many of the record numbers of voters who spoiled their ballot papers and the millions who stayed at home in those elections were not apathetic, but there was no political party capable of channelling that rage.

The United Left (IU), which was dominated by the Communist Party of Spain (PCE), had increased its support, but it was too rigid and bureaucratised to capture much of the enthusiasm of the tempestuous movements which were developing.

Meteoric rise

This was the context in which new party Podemos (‘we can’) was created in 2014 and grew meteorically. Less than a year old, Podemos gained 8% of the vote in the European elections in 2014.

Pablo Iglesias, one of its founders, was addressing crowds of 150,000 at rallies in Puerta del Sol as the year closed.

In the 2015 general election Podemos came third, gaining over five million votes – 20% of the total. That election announced the end of stability for the capitalist class in the Spanish state. Four general elections were held in four years and none of them returned a majority for any party or coalition.

The most important factor in the growth of Podemos was its radical programme. It pledged to ensure everyone had a decent income and the right to housing. It promised to raise wages, lower the retirement age and nationalise key sectors of the economy, saying it would defy the EU and refuse to pay Spain’s enormous debts.

At a time when many were disgusted by the austerity that PSOE had carried through, it gained popularity with a combative approach, proclaiming its intention to replace PSOE as the main opposition party.

Podemos also promised to give ordinary people control of the organisation. It offered new methods of participation – including through innovative online methods. Its election candidates were also selected online in primaries and it offered to link up with IU in a united front.

Podemos’ initial gains were impressive, but in the years since it has failed to live up to the expectations of workers to fight the capitalist establishment – which could only have been met by a revolutionary socialist programme that breaks with capitalism.

A setback in the second general election fought in 2016 provoked a crisis in the party, now in an electoral alliance with IU as Unidas Podemos (“United We Can”, or UP).

The dominant idea in the leadership of the party at the time was that, having won the support of those who wanted radical change, it would be necessary to create a more ‘respectable’ image in order to broaden its appeal.

Its leaders stopped talking about nationalisation and other radical policies and began describing its politics as ‘social democratic’. The result was that UP lost a million votes in 2016.

Following the losses, at Podemos’ second national conference in 2017, co-founder Íñigo Errejón argued that Podemos should turn even further to the right.

Role of working class

At that time, Iglesias opposed such a strategy. Errejón was decisively defeated, but Podemos had not built a stable base of support in the working class or strong democratic structures, which would have assisted it to weather the storms ahead and opportunist pressures that would inevitably arise again.

The working class, because of the crucial position it occupies in production and the functioning of society, as well as its ability to cripple capitalism through strike action, plays the key position in the movement to replace capitalism with socialism.

As Podemos was developing, the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI – the socialist international organisation to which the Socialist Party is affiliated) called for the setting up of structures that would enable working-class people – including those who worked long or unpredictable hours – to participate in the party and determine its direction.

It was difficult for workers with limited time to participate meaningfully in unfocused discussions that could continue indefinitely. Discussions should have been focused around resolutions about the way forward for the party.

Instead, the supposedly ‘horizontal’ lack of structure of the party and the reliance on online referenda meant that the organisation was dominated by those who have the most time and resources to make their case to the membership, but not necessary the firmest opposition to capitalism.

Turning point

The political terrain on which Podemos was operating changed radically in 2018, when PSOE leader Pedro Sanchez successfully ousted PP leader Mariano Rajoy and replaced him as prime minister.

Given the powerful desire of workers to be rid of Rajoy, it was correct for Podemos to enable Sanchez to form a government and help to end the reign of the PP government, while always working to expose the real character of PSOE.

But Podemos went much further than this – offering Sanchez, even at times pleading with him, to let Podemos join PSOE in government, even as Sanchez was exposing himself more each day as a reliable tool for capitalism against the workers.

This mistaken attitude to PSOE lost another sixth of their seats at the 2019 elections, under half of its peak votes and seats.

After two elections in 2019 failed to give him a majority, Sanchez gave Podemos what they asked for, and Iglesias and several other leaders of Podemos and IU joined the government and were given ministerial portfolios.

Despite vague promises to serve workers’ interests Sanchez kept in place the cuts budget he inherited from the PP and obediently carried out more austerity demanded by the EU.

This absorbtion of Podemos’s leaders into the capitalist establishment struck at the heart of what had made Podemos popular. This has particularly damaged Podemos where the relation between powerful local national identities and the Spanish state have not been resolved.

Catalan national question

The powerful upsurge in the Catalonian independence movement from 2017 – which included some features of revolution – was an important test for Podemos, which it utterly failed.

After Spanish state forces brutally repressed those who tried to take part in the referendum for independence in 2017, Podemos’s response was to sit on the fence, and merely bleated that there should be a referendum “mutually agreed” by both sides.

The damage was done not just in Catalonia itself, where it was pushed from having won the election in 2016 to sixth place. It was also virtually wiped out in Galicia and lost half its positions in the Basque area.

No left force will be able to build support in Catalonia in this period unless it respects the right of self-determination of nations.

The rise and fall of Podemos is full of lessons for the global movement of the masses against austerity. Its formation with, initially, a radical programme was a step forward from the capitulation of the former workers’ parties because it offered a political resistance to capitalism.

But its failures to adopt or orientate to the methods of the workers’ movement meant that it succumbed, in a similar way to the social democratic parties, to the pressures of the capitalist political system.

The meteoric rise of Podemos demonstrated the appetite that the Spanish masses have for a new mass workers party, which, with a clear socialist programme and a leadership democratically accountable to a mass membership, could provide a real alternative to the capitalist parties.