Council’s historic victory over the Thatcher government

|

|

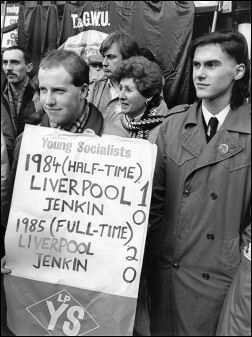

Liverpool City Council demonstration, November 1983, photo Paul Traynor |

ON 9 July 1984 Liverpool City council, led by Militant (the Socialist Party’s predecessor), won a sensational victory over the ruthless Tory government of Margaret Thatcher.

They secured extra funding for the council’s urban regeneration programme.

The principled stand by the 47 Liverpool Labour councillors, allied to a mass movement of the city’s workers and wider working class, stands in stark contrast to today’s sleazy and spineless Labour leaders.

Tony Mulhearn, one of the Liverpool councillors subsequently victimised by the state and witch-hunted by the Labour Party leadership, explains the successful struggle 25 years ago.

“DANEGELD,” THUNDERED the Times. Danegeld was the tribute in gold demanded from the English rulers in the thirteenth century by the invading Danes in exchange for not engaging in pillage and plunder.

“Two unlovely black eyes,” declared the Daily Mail, when it condemned the Tory environment secretary Patrick Jenkin’s retreat over additional funding for Liverpool City council in 1984. It wrote: “The Trotskyites and others of the hard left who run Liverpool have had the best of the fight with him in their threat to defy the law on that city’s overspending.”

“A cowardly deal” was the headline of the Daily Express which went on: “Patrick Jenkin seems to have bought himself some peace from the Militant-led Liverpool City council. This is a shoddy and cowardly deal… Mr Jenkin has shown that defiance pays.”

These headlines were just some of the reactions to the Militant-led Liverpool City council’s success in securing £30 million from the Thatcher government on 9 July 1984.

In contrast to the outrage expressed by the media were the scenes of exultation that greeted the councillors when they reported the outcome of the negotiations with Jenkin to a 600-strong meeting of the Liverpool District Labour Party.

Programme

|

|

Liverpool City Council: Celebrating the climb down of government minister Patrick Jenkin, granting Liverpool City Council more money, photo John Smith |

Liverpool was the only council to secure extra funding from a Thatcher government wedded to the principles of monetarism espoused by the likes of economists Milton Friedman and Frederick Hayek, whose monetarist model was also embraced by Chile’s bloodthirsty dictator Augusto Pinochet with murderous consequences for the Chilean working class.

This victory enabled the council to carry out its electoral programme, included the building of 5,000 houses, opening six new sports centres, creating 2,000 jobs and refusing to carry out £10 million worth of cuts which had been the legacy of the Liberal/Tory alliance which had ruled Liverpool for the previous 20 years, with a short interregnum of Labour rule.

This anniversary is particularly significant as it occurs at a time of national and global capitalist upheaval, and the mind-boggling revelations about the behaviour of MPs who have aped the actions of the greedy bankers by using every phoney device to stuff their pockets with gold.

The next thing to come under the spotlight should be the lucrative consultancies and directorships of MPs and ex-ministers who have become millionaires overnight having presided over the privatisation of publicly-owned companies.

Also, temporarily hidden from the public gaze, the private porkers in the financial sector continue to stack up personal wealth. A couple of examples show that, in spite of the near-criminal activity of the bankers, Peter Mandelson’s philosophy of ‘being relaxed about people being filthy rich’ is alive and well and, in spite of Brown’s bluster about ‘responsible banking,’ continues to shape the outlook of New Labour.

In 2008, in the midst of the economic crisis, bankers earned on average £255,000 more than their counterparts in other branches of private industry. Incredibly Northern Rock’s non-executive directors’ salaries rose by 33% after it was nationalised.

Recently, City sources revealed that RBS, bailed out by the taxpayer, and milch cow for Fred ‘the Shred’ Goodwin, made a deal with its head of global banking John Hourican which grants him a package which, given the rise in the RBS share price, doubles his stake on paper to £11 million in two months. And only last week the government approved a £10 million remuneration package to Goodwin’s successor, Stephen Hester.

Against these figures, the frame-up against the 47 Liverpool Labour councillors by the District Auditor, who charged them with losing the Liverpool rate payers £106,000, is truly grotesque.

Terry Fields and Dave Nellist were two MPs who gave unconditional support to the Liverpool City council and who were expelled from Labour as a result of the witch-hunt unleashed by the then Labour Party leader (now Lord) Neil Kinnock.

His Lordship has been uncharacteristically silent about the ‘grotesque chaos’* overwhelming a Parliamentary Labour Party that, as a consequence of his action in unleashing a pogrom to cleanse Labour of socialists, no longer remotely reflects the interests of the working class (* the scurrilous term used by Neil Kinnock in his infamous 1985 Labour Party conference speech to attack the Liverpool 47).

In contrast to the behaviour of the current crop of charlatans, Terry, Dave and later Pat Wall in Bradford, accepted only the average wage of the workers they represented who were working in industry.

It is a tribute to their dedication to socialism that their names are mentioned more and more over the airwaves and in the local press during public discussion on the current parliamentary revelations. For example, I was contacted by Radio Merseyside to explain the role of Terry Fields as a firefighters’ rep and MP in the context of the present parliamentary bacchanalia.

Record

|

|

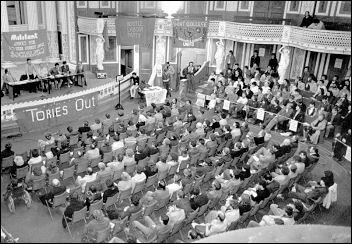

Militant Rally in Liverpool 9 April 1984. Steve Sullivan, a miner from Sutton Manor mine speaking at St George’s Hall, photo Jacob Sutton |

The passage of time has not diminished the achievements of the 47, nor undermined the importance of the struggle. In spite of the distortions of establishment spokespersons, aided and abetted by the lies of right wing parliamentarians and trade union leaders, the record of the 47 remains stubbornly intact.

The 47 inherited a catastrophic financial situation when they took control in 1983. The outgoing Liberal-Tory alliance had deliberately underspent throughout the 1970s as a cynical ploy to maintain electoral support. In one year they actually cut the rates (a forerunner of today’s council tax).

This was achieved by increasing rents, terminating the house-building programme and shedding thousands of jobs, in addition to cuts in other sectors. Thus Liberal council leader Trevor Jones was able to claim he presided over the lowest rate increases in Liverpool’s history. He was knighted by a drooling Thatcher for services rendered.

Thatcherism

These events had as their background the Thatcher government’s dislike of local government or, more precisely, Thatcher’s hatred of local democracy which often then resulted in the election of Labour councils.

Part of the Tories’ programme when they were elected in 1979 included decentralising state power and devolving decision-making to localities. In fact, the opposite took place. Using the device of the block grant system which penalised local authorities who exceeded the government’s prescribed spending limits, the government succeeded in slashing local authority expenditure.

The percentage of local expenditure financed by central government fell drastically from 61% in 1979-80 to 48% in 1985-86. That 13% shortfall had to be funded by local councils if services were to be maintained.

However, such was the Tories’ ruthless determination to drive down local expenditure, they introduced a policy of rate-capping with savage penalties for those councils who exceeded the limitations imposed by central government. For every £1 breach of expenditure, £2 would be lost in rate support grant.

Initially, all Labour-controlled local authorities had agreed to support a campaign against the policy of rate-capping. Amongst the leaders of this campaign, it is incredible to recall, were David Blunkett and Ken Livingstone, with Neil Kinnock as their parliamentary cheerleader.

However, the consequences for Liverpool were more severe than all other authorities. In 1984-85 the total target of expenditure set by the government for all English authorities was 6% lower than their expenditure in 1980-81, but Liverpool’s target, as a consequence of the rating policy of the Liberal/Tory alliance, was 11% lower than its spending in 1980-81.

Liverpool’s officials estimated that between 1978-79 and 1983-84, the city had lost between £26 million and £34 million in government grants as a result of the government lowering Liverpool’s spending target. This was the £30 million (on average) that the council explained the government had stolen.

Thus, the years of rate-slashing policies by the Liberal-Tory alliance in Liverpool meant that the financial position of the city was in even greater dire straits than all other local authorities.

The government’s policies meant that, in order to balance the books, a local authority would either have to increase the rates, sometimes massively to compensate for Tory cuts, or savagely cut back on jobs and services.

The Liverpool District Labour Party’s policy was to reject both of these options and instead to carry out its electoral promises. In the elections of 1983 a key component of the Liverpool party’s electoral programme was ‘No rate or rent increases to compensate for Tory cuts.’

That campaign explained to the Liverpool electorate the consequences of Liberal/Tory rule. The campaign also explained the pernicious slashing policies of the Tory government and gave a commitment that a radical socialist programme would be implemented. This included house building, job creation, rent reductions and improvement of services, linked to a campaign to retrieve funding from central government. The result was the magnificent electoral victory in 1983 with Labour gaining 12 seats, giving Labour 51 seats against the Liberal/Tory total of 48.

The massive financial crisis already described, which Liverpool Labour inherited, was seen as a reason for the implementation of the electoral programme rather than, as is usually the case with all the pro-capitalist politicians, a reason to retreat.

If Liverpool’s expenditure had increased at the same rate as other authorities and even within government guidelines through that period, then the city’s target set by the government for 1984-85 would have been much higher. In addition to the problems caused by the Liberals’ financial jiggery-pokery through the 1970s and early 1980s, in 1983 the incoming Labour council inherited a budget which included £8 million to £10 million of unallocated cuts.

Against this background it was a diabolical lie for the right wing to allege that the crisis in Liverpool was of the 47’s own making. Jack Straw, for instance, who in 1984 advocated a rate rise of 60%, has to this day never retracted the lies spewed out by him and his colleagues.

His excuse over the scandal about his parliamentary claim for full council tax when he had already been allowed a 50% discount was that “accountancy does not appear to be my strongest suit.” This admission serves to underline his ignorance about the real depth of Liverpool’s financial crisis that even Patrick Jenkin was compelled to recognise.

Mass struggle

|

|

Liverpool City Councillors hold press conference at House of Lords 26 Jan 1987, photo Dave Sinclair |

But the victory was not achieved merely by slick negotiation between the councillors and Patrick Jenkin. Jenkin’s promise to ‘do his very best’ to ameliorate some of Liverpool’s problems wasn’t solely due to his compassion having seen, in his words, ‘housing conditions the likes of which I’ve never seen.’

It was also prompted by the mass support enjoyed by the council evidenced by the 1,000-strong demonstration which followed him around the housing estates which he viewed on his visit to Liverpool.

He was also conscious of the magnificent electoral support as well as the physical support shown by the great demonstrations that marched through the city in support of the council’s policies, particularly the demonstration on budget day the previous March when a one-day strike took place, supported by 30,000 local authority workers. 50,000 people marched through the city that day in support of the council’s proposed ‘deficit budget’. That support was the reason Thatcher had despatched Jenkin to the city to get a real flavour of the situation on the ground.

Celebration

The council meeting following the funding victory was greeted with scenes of jubilation more akin to welcoming a returning football team having won the FA cup. The lobby of the council saw local authority workers, striking miners, young people, unemployed and parents with their young children, all listening to the victory speeches. Labour speakers were greeted with cheers, while over the benches of the Liberals and Tories hung a mood of demoralisation.

The support for the council was based on concrete changes to better people’s lives. For instance, before the local press joined the Rupert Murdoch/Robert Maxwell media axis in its demonisation of the councillors, the Daily Post carried a headline ‘House-proud city has got it right.’ It reported the comments of a housing expert, Alice Coleman, who had carried out extensive research into housing conditions nationally and internationally.

‘Liverpool,’ she declared at a meeting to assess the council’s housing policy, ‘has got it right.’ She completely concurred with the main thrust of the Urban Regeneration Strategy and the council’s conviction that the majority of people preferred to live in traditional houses.

Moreover, the spin-off effect of the city’s housing programme on employment had been publicly recognised by building companies who are not usually friends of Labour. In the three years from April 1983 to May 1985 it was estimated that 6,489 jobs had been generated in the private sector as a result of the house-building programme.

Twenty-five years late, the chattering classes agonise over the disengagement of people in general from politics and their disillusionment with the mainstream parties. Chat shows on various agencies of the media usually draw the conclusion that the party leaders, particularly Gordon Brown, lack charisma, or they don’t have the ability to crack a good gag.

The logic of this argument is that New Labour should persuade Ken Dodd to lead the party and they would romp home at the next election with a massive majority based on a 99% turnout!

The Liverpool 47 attracted the highest Labour vote in history, and higher than in any election since world war two even though the population of the city had declined from 700,000 in 1945 to 460,000 in 1983. While turnout for local elections in recent years has ranged from 11% to 20%, the turnout in 1983 and 1984 was 45% to 55%. A clear message that if policies which correspond to the needs and aspirations of the working class are implemented, then the support will be forthcoming.

It was this level of support that gave the ruling class and its allies at the tops of the Labour movement an enormous problem.

The council leaders warned the workers that the Tories would bide their time and wait for the opportunity to take their revenge, particularly with the vengeful Margaret Thatcher determined to crush any opposition. They explained the urgency of stepping up the national campaign to persuade other major councils to take the Liverpool road and to compel Thatcher to retreat.

Tragically, this strategy did not succeed. One by one, the other councils involved in the anti-rate capping campaign capitulated under Tory pressure, aided and abetted by the national Labour leadership, particularly by the treachery of Labour leader Neil Kinnock. Ken Livingstone in London and David Blunkett in Sheffield, sounded the retreat which turned into a rout, eventually leaving Liverpool in isolation. This retreat was accompanied by a hysterical media campaign designed to isolate Liverpool, with deputy Labour leader Roy Hattersley accusing the Liverpool councillors of ‘literal corruption’.

In spite of their unparalleled record of achievement, the power of the state eventually prevailed. Thatcher’s district auditor, supported by the House of Lords, removed the 47 councillors from office, cheered on by the Labour leaders. Kinnock and his lieutenant, witchfinder-general Peter Kilfolye, finished the job on behalf of the capitalist state by expelling the majority of the 47 from the Labour Party.

Since then many gallons of ink, acres of newsprint, and speeches by right wing charlatans have attempted to denigrate the 47’s period of office. But the record has been written in concrete buildings and stands as a monument to the socialist achievements of the Liverpool City council of 1983-87. Achievements symbolised by the incredible victory over Patrick Jenkin 25 years ago.