Only a democratic socialist plan of production can stop price hikes and shortages

Iain Dalton, Socialist Party national committee

“We were already having problems with food prices… What countries are doing now is exacerbating that, and the war is putting us in situation where we could easily fall into a food crisis,” said Maximo Torero, chief economist for the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation.

Among the major food producing nations, Russia is the world’s top wheat exporter, with 17% of the global market, and Ukraine third with 12%. Ukraine is the top exporter of sunflower seeds with 30% of the market, and Russia second with 27%. Ukraine is also the fourth largest exporter of corn, with 17% of global exports. 50 countries rely on Ukraine and Russia for 30% or more of their wheat supplies.

Directly affected by the war are shipments of grain from Black Sea and Azov Sea ports such as Odessa, Nikolayev, and Mariupol – which have shut down since the onset of the conflict. Almost half of the winter harvest of corn hasn’t been shipped out of Ukraine.

Also, the cutting off of Russia from the SWIFT financial payment system has had a knock-on effect for shipments from the country. Indeed, the threat of sanctions is leading to companies ‘self-sanctioning’, ie not committing to shipments of Russian commodities for fear of being hit by future sanctions.

Harvest disruptions

The harvesting of winter sowings in Ukraine will undoubtedly be affected, both in terms of how well crops can be tended and, if the war continues, the degree to which they can be harvested.

The threat of further sanctions will likely lead to reduced summer sowings of grains in Russia. And while higher prices may lead to increased sowing levels in other countries such as the US, as an article from Dutch financial services company ING warned: “If we see a prolonged disruption in supply from Ukraine and Russia, increased plantings from other producing countries may help, but clearly will not offset the full potential losses from these Black Sea producers.”

All these developments come on top of already soaring food prices, a result of numerous factors, including the impact of Covid-19 on worker absences and the ongoing supply chain crisis causing delays in shipping.

Another key factor is the environmental crisis, such as the heatwave and drought in Canada that adversely impacted on durum wheat used in producing pasta. It’s predicted that the cost of pasta in the UK could increase by 50% this year.

Heavy rains in China means its wheat crop might be 20% less than expected, although China’s 18 months of wheat reserves can cover this shortfall.

The increased cost of industrial inputs into farming is an additional factor. The price of urea, a key component in some fertilizers – largely produced in Ukraine and Russia – has skyrocketed. Fuel, necessary to run farming vehicles, has also seen its price soar.

Midwife of revolution

Spikes in food and other commodity prices have often been midwives of revolution. As the Economist journal warned: “All this may lead to unrest. President Anwar Sadat tried to do away with Egypt’s bread subsidy in 1977; he reversed his decision within days after riots that had to be quelled by the army. Ethiopia’s revolution of 1974 followed an oil-price shock. Higher food prices in 2008 and 2009 helped set off the revolts of the Arab spring, and protests that led to the toppling of Omar al-Bashir in Sudan in 2019.” And let’s not forget the February 1917 Russia Revolution started by a strike of women workers demanding bread!

Egypt is one of the countries particularly affected by the current war, with 86% of wheat imported from Russia and Ukraine. Lebanon is another net importer of wheat. The price of flatbread there has already increased 400% over the previous two years and after the Beirut port explosion destroyed the main grain silos, the country has only a month’s supply of wheat stored.

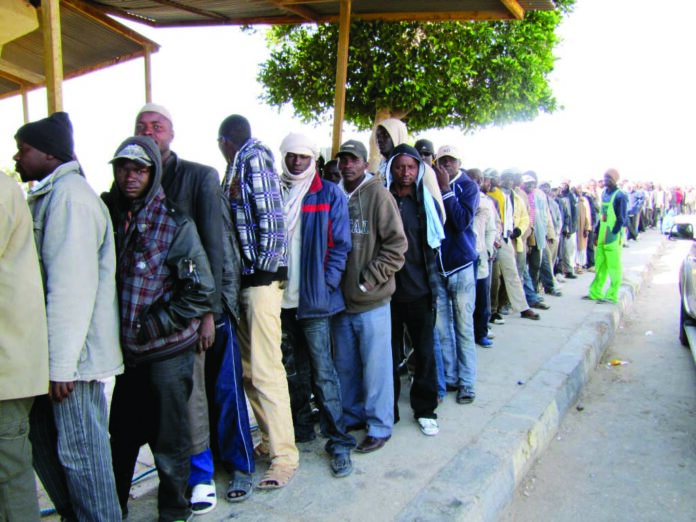

Food inflation across sub-Saharan Africa was already running at 9% in 2019-20, and has been running at higher levels more recently.

Optimistic pro-capitalist commentators will point out that theoretically there are sufficient surpluses in various parts of the world that could potentially meet the shortfall in supply. However, that would require society being organised on the basis of meeting the needs of people, rather than the profits for a handful at the top.

Unlike the generous spirit shown by millions of ordinary people in donating to help aid refugees from the war, the response of many capitalist governments to this latest food crisis is to increase protectionist trade measures further. Hungary has banned all grain exports. Serbia is banning exports of wheat, corn, flour and cooking oil. Indonesia has limited palm oil exports.

Meanwhile, just four companies dominate almost 75% of grain trading.

Archer-Daniels-Midland reported a 22% growth in profits year-on-year in the fourth quarter of 2021, and upping its dividend payouts. Bunge increased its profits by 17% in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Cargill reported the biggest profit in its 156-year history in its 2020-21 financial year; while Louis Dreyfus posted profits for first half of 2021-22 financial year of $336 million, up a whopping 167%!

Under capitalism the misery of workers goes hand in hand with profit bonanzas at the top.

Only by bringing the big grain traders and the supermarket and logistics giants into public ownership, under democratic workers’ control and management, can we guarantee that the food produced in the world will actually ensure everyone can be fed at a genuinely affordable price.