Stonewall riots’ legacy shows need for socialist struggle to win LGBT+ liberation

Michael Johnson, Socialist Party LGBT+ group

Pride events around the world this year are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, widely seen as the birth of modern LGBT+ rights movements.

The original pride marches following the riots were political protest marches. Today, big business has taken them over to advance the cause of private profit, and at a safe historic distance capitalism ‘celebrates’ Stonewall in a hypocritical effort to attract the ‘pink pound’.

While 50 years of struggle since Stonewall have won positive changes in laws and attitudes, today, a mass, working-class movement to end LGBTphobia – and the capitalist system which sustains it – is still needed.

There had been movements in the struggle for LGBT+ rights prior to the riots. The campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in the UK won some victories in 1967. In the United States, there was work by groups like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis.

The Mattachine Society was founded by communists and trade union activists, one of the earliest “gay rights” organisations in the US. It had been involved in campaigns challenging homophobic policing and workplace firings.

However, by the time of the Stonewall riots it had largely become focussed on avoiding confrontation and “assimilating” into the official institutions of capitalist society. This saw its support decline in the lead-up to the riots.

This was at a time of collective struggles like the US civil rights, Black Panther and anti-war movements, and also more individualistic phenomena like 1960s ‘counterculture’. In other parts of the world, there were national liberation struggles and events like the revolutionary general strike in France in May 1968.

There was an atmosphere of resistance to the status quo, but with many different ideas about how to achieve liberation, sometimes confused and contradictory. Meanwhile, repression and harassment of LGBT+ people were widespread.

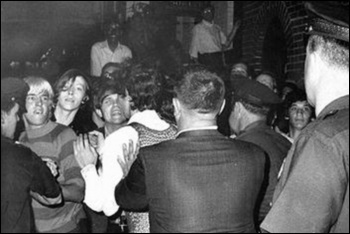

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street was one of several New York bars run by the mob due to legal prohibition of gay clubs. It was the only such bar where dancing was allowed.

This was its main draw since reopening as a gay bar, along with its location in New York’s bohemian Greenwich Village. It was especially popular with younger LGBT+ people.

Police raids on gay bars were frequent, once a month on average for each bar. Bar managements usually knew beforehand due to police tip-offs, and raids occurred early enough in the evening that business could commence after the police had finished.

During a typical raid, police turned on the lights, lined up the customers, and checked their identification cards. Those without ID or dressed in full drag were arrested; others were allowed to leave.

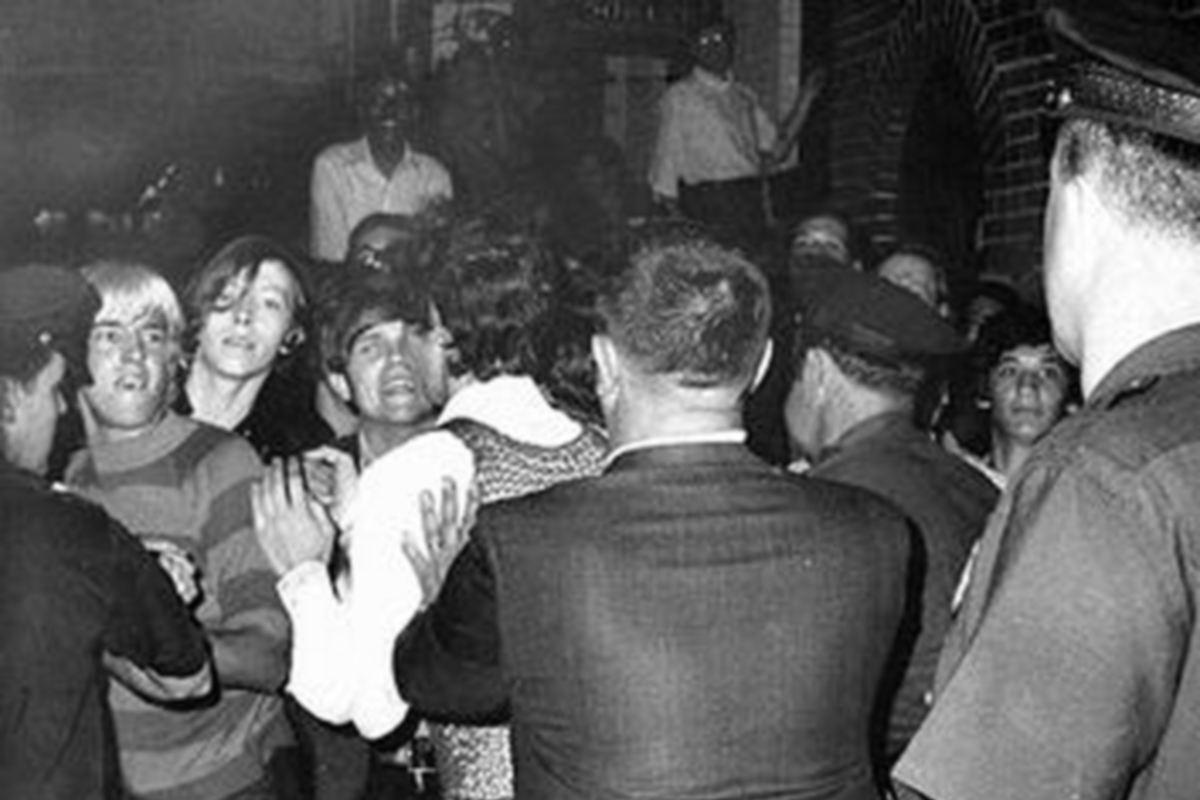

On Saturday 28 June 1969, the Stonewall Inn was raided as normal. However, that night, the raid did not go as planned.

Fed-up patrons refused to present their identification or have their gender ‘verified’. The police decided to take everyone present to the police station, after separating customers wearing drag in a room in the back of the bar.

Patrons who had not been arrested were released, but they did not quickly leave as they would usually have done. Instead, a crowd began to grow and watch outside the bar. Within minutes, over a hundred people had gathered.

As officers escorted customers to police wagons, one arrested woman shouted to bystanders: “Why don’t you guys do something?” An officer attacked her while forcing her into the back of the car, the outraged crowd went berserk, and the riot began.

They pelted the police with coins, ‘paying off’ the cops just as bar owners had to if they wanted to avoid raids. The crowd continued to grow.

One participant described it as “just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head… Everyone in the crowd felt that we were never going to go back. It was like the last straw.

“It was time to reclaim something that had always been taken from us… It was total outrage, anger, sorrow… We felt that we had freedom at last, or freedom to at least show that we demanded freedom… The bottom line was, we weren’t going to go away. And we didn’t.”

By 4am, the police had regrouped and nearly cleared the streets. However, this was not the end of the fight. Graffiti quickly appeared on the walls of the Stonewall Inn, with slogans declaring “drag power”, “they invaded our rights”, “support gay power”, and “legalise gay bars.”

The next night, rioting again engulfed Christopher Street. Thousands had gathered in front of the Stonewall, and street battling raged until 4am for the second night running.

Further protests and riots occurred against the local newspaper, Village Voice, after it ran reports of the riots which described them as the “forces of faggotry” and “Sunday fag follies.” One witness to these remarked: “The word is out… The fags have had it with oppression.”

New York’s Stonewall Inn in 1969, photo by Diana Davies/New York Public Library/CC (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

Wave of political struggle

The riots themselves were an outburst of stored-up anger. The real change started to happen because they were also a watershed moment in the public visibility of LGBT+ repression and conflict, and a wave of organisation and political struggle followed.

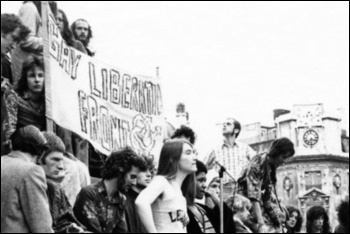

The Gay Liberation Front was quickly formed, directly challenging politicians, the police and media on LGBTphobia on a regular basis. This was followed by the Gay Activists Alliance. It sought to focus on LGBT+ rights as a single issue, in contrast to the wider struggles the Gay Liberation Front tried to connect with.

Increased militant activism in the fight for LGBT+ rights wasn’t only occurring in New York. Frank Kameny, a leading organiser of the Mattachine Society, estimated that prior to Stonewall there were around 50 to 60 LGBT+ rights groups in the US. A year after Stonewall there were “at least 1,500.”

These groups and other activists organised the Christopher Street Liberation Day parade on the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Another year later, these parades would spread across the US and internationally, the basis of today’s pride events.

These early marches were a far cry from the corporatised prides of today. They had radical demands and liberation to the fore. Activist Marsha P Johnson, who had taken part in the riots, explained she joined the marches as “I want my gay rights now!”

While the Stonewall riots where not the start of the fight for LGBT+ rights, they played a major role in sparking the steps forward in US organisation and struggle in the ensuing years, from challenges to anti-LGBT+ legislation to the battle against the Aids crisis and recent successes such as marriage equality.

Stonewall sparked similar steps forward around the world, including the spread of pride events, with now over 100 occurring across the UK. And also activism like the development of a sister Gay Liberation Front group which played a similar role in Britain.

Britain’s 1984-85 miners’ strike was also crucial in linking the organised working class and LGBT+ rights movement. Groups like Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners joined the struggle against a common enemy, the Tory government and its big business paymasters. This was part of the process of the trade union movement taking up the struggle against LGBT+ oppression more seriously.

LGBT+ struggle today

Last year, a British government survey of LGBT+ people found two-thirds are afraid of holding a same-sex partner’s hand in public, or being open about their sexuality, for fear of a negative reaction.

More than a quarter of young LGBT+ people in education have experienced verbal harassment, insults or being forcibly outed. Nearly all LGBT+ people experiencing harassment do not report it, citing reasons like “it happens all the time” and the feeling that nothing would change if they did.

A new report from the Trade Union Congress has found that 68% of LGBT+ people have faced sexual harassment at work. Of these, two in three did not report the harassment they faced to their employers. Furthermore, a quarter of those who didn’t report chose not to for fear of being outed.

Homophobia and transphobia are rooted in society based on class. Capitalism defends the interests of super-rich big business owners at the expense of ordinary people who create the goods and services that make the owners’ profits. The system has a vested interest in fostering division and prejudice to maintain the privilege of the ruling elite.

When in crisis like today, capitalism threatens even the gains won through struggle in the past. Pro-capitalist politicians try to whip up bigotry to distract from the real enemy, the capitalist class.

And austerity, trying to make ordinary people pay for the bosses’ economic crisis, hits groups already discriminated against under capitalism hardest. The housing crisis, cuts to homelessness services and shelters, cuts to NHS funding, and many other austerity attacks affect all working-class people, and are hitting LGBT+ people extra sharply.

So defeating austerity and LGBT+ oppression requires rebuilding working-class struggle against capitalism. By joining in the struggle alongside workers and young people, and fighting for a socialist alternative, we can win!

A socialist society, based on public ownership and democratic working-class control of society’s resources, would be run by the majority, for the majority. By planning to provide for all instead of competing to enriching the bosses, the conditions of inequality and scarcity which sustain prejudice would begin to evaporate, and personal relationships could be freed from the restrictions imposed by class-based society.

In building such a movement, political pride events are as important as ever. Taking the arguments for LGBT+ liberation into the trade unions and workplaces, onto the campuses and estates, and connecting them to the struggle for socialist policies, we could rally support behind the call for genuine liberation of the working class and all oppressed people.

Since 2010 we’ve seen large numbers of LGBT+ services close due to lack of funding. LGBT+ people are disproportionately more likely to experience mental health problems or homelessness; all areas where we are seeing huge cuts.

We need to link up with workers to fight back against these cuts, and the housing crisis, poverty pay, precarious work, and attacks on our terms and conditions faced across the country.

The Tories – the party of big business – are in crisis. In the last three years two prime ministers have been forced to resign. The splits over Brexit have been laid bare by the shenanigans in parliament over May’s deal. Central for all of us fighting against oppression and austerity is a campaign for a general election to get the Tories out!

But the fight for a Jeremy Corbyn-led government with socialist policies also means fighting to remove the representatives of capitalism in the Labour party – the Blairites who pass on the cuts and attack Corbyn’s anti-austerity platform – and to transform Labour into a mass workers’ party.

At pride this year, we should not just celebrate the memory of the Stonewall riots, but continue their legacy of organising for militant action. Not just at once a year pride events, but in our trade unions and community groups; fighting not just against individual attacks, but for a change in society, for socialism, that means genuine liberation for all.