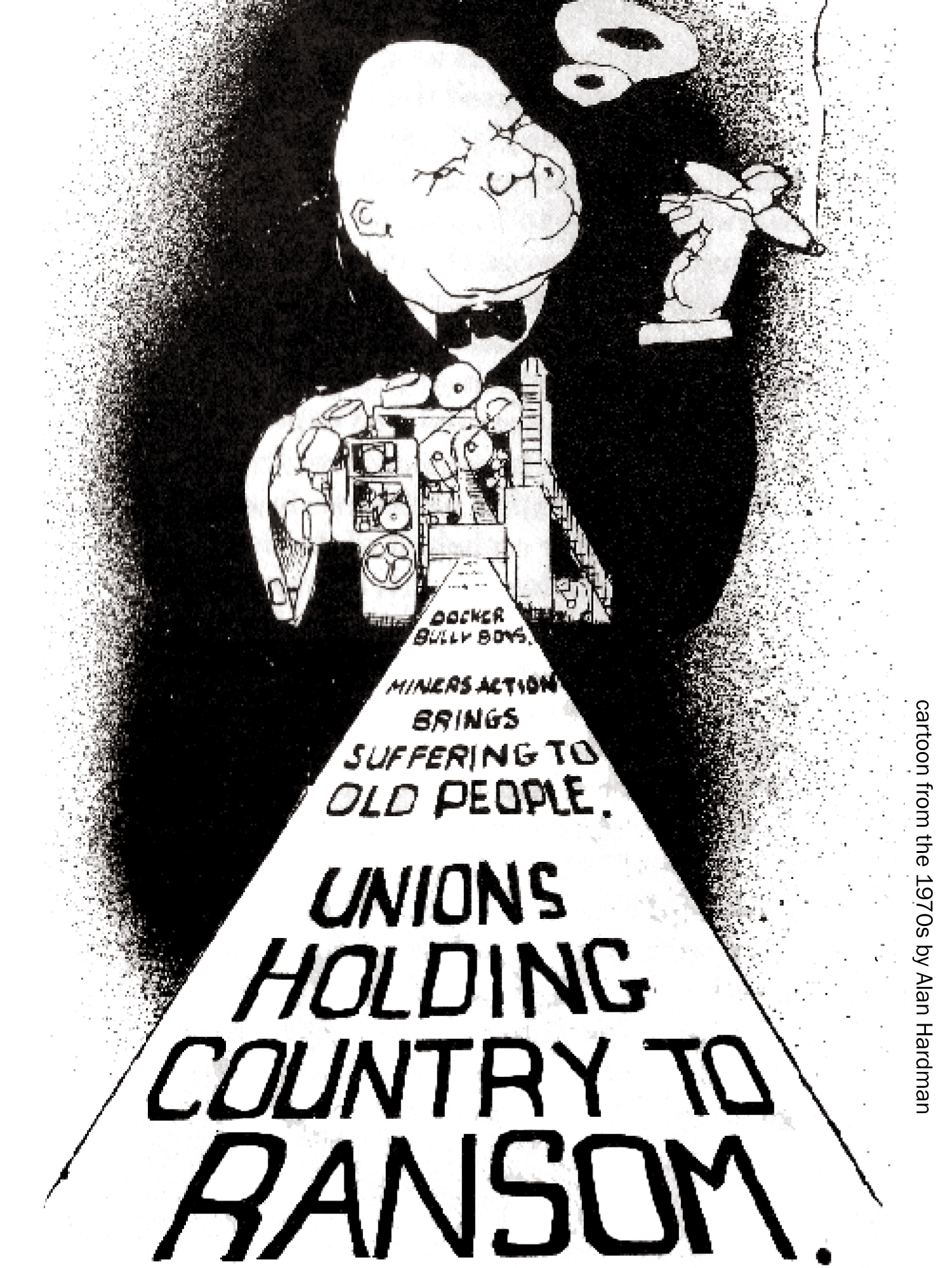

Cartoon attacking press bias against striking workers from the 1970s by Alan Hardman (Click to enlarge: opens in new window)

In 2008 Peter Taaffe, Socialist Party general secretary, reviewed the book Flat Earth News by Nick Davies. This is a devastating book which lifted the lid on the workings of the media. Davies has since led the Guardian investigations into the News of the World phone hacking scandal. We carry an extract of the review here. The full review can be read in Socialism Today issue 117 April 2008, printed two years before the Con-Dem government was formed.

There already exists in Britain a fairly widespread suspicion, if not a clear conviction, that the capitalist media – television, press, radio and, increasingly, websites allied to these information outlets – are biased and lack veracity. The ‘red tops’, the tabloid press, are the greatest sinners, with Rupert Murdoch’s Sun in the vanguard.

The American media critic Ben Bagdikian has traced the corporate takeover. In 1997, he wrote about the corporations producing America’s newspapers, magazines, radio, television, books and films: ‘With each passing year… the number of controlling firms in all these media has shrunk: from 50 corporations in 1984 to 26 in 1987, followed by 23 in 1990, and then … to less than 20 in 1993. In 1996 [it] is closer to ten’. By 2004, he found the US media was dominated by just five companies: Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch’s News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany and Viacom.

At the same time, the number of people employed in the industry fell by 18% between 1990 and 2004. But the average operating profit margin of these media corporations was 20.5%, approximately twice as high as the level among Fortune 500 companies.

Churnalism

A substantial part of the book deals with the plight of journalists who, through relentless pressure, have been reduced to ‘churnalists’, merely passing on unchecked stories from outlets such as the Press Association (PA), Reuters and Associated Press (AP).

In his book Nick Davies recognises that there was no golden age, but a certain latitude did exist in the past, which allowed some, particularly well-known figures, many of a left persuasion, to find a platform for airing views which questioned, if not the system of capitalism, the consequences that flowed from it.

Now, as with other professions, the remorseless pressure of neoliberalism has reduced journalists to mere cogs who churn out information force-fed to them. There is an additional factor not recognised by Davies.

In the past, the pressure of a powerful trade union movement allied to widespread support for socialist ideas compelled the capitalist press to reflect this in their coverage. They were compelled to give a platform to leading left Labour and trade union figures, including strike leaders and even the occasional Marxist.

Murdochism

Some newspapers like the Daily Mirror tilted to the left, towards Labour, when it was at bottom a workers’ party. All this was squashed by the advent of ‘Murdochism’ and the brutal capitalist methods he personified.

In a Cardiff University investigation, commissioned by Davies, of the so-called ‘quality press’ – The Times, The Guardian, The Independent and the Daily Telegraph – 60% of “quality-print stories consisted wholly or mainly of wire copy and/or PR [public relations] material”. Only 12% of stories, the researchers said, were generated by the reporters themselves.

PR has grown astronomically since the 1980s, thanks to companies and political parties. There are now 48,000 PR representatives compared to 45,000 journalists in Britain.

On behalf of the Blair government, Alistair Campbell, Blair’s press secretary, used every dirty method in order to suppress the colossal criticism which had built up over the war in Iraq. The monstrous lie over Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction used to justify the war is a tale often told.

However, Davies gives even more graphic detail about this, the attack on the journalist Andrew Gilligan over the ‘sexed-up’ intelligence report justifying the war, and many other examples of New Labour’s responsibility for the war. Campbell was successful in diverting attention from the original question about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction.

His bullying, even of capitalist journalists, was taken to unheard of lengths by his New Labour acolytes. Davies reports that ministers in the government approached some newspapers with “explicit invitations to sack Andy McSmith, the political editor of the Independent, Paul Eastham, the political editor of the Daily Mail, Christian Wolmar, the transport editor of the Independent… and Andrew Marr, when he was editor of the Independent”.

The concentration of media ownership has now produced a situation whereby ten corporations own 74% of the private media. This monopolisation meant that 8,000 journalists working outside of London lost their jobs between 1986 and 2000.

It is difficult to fault Nick Davies’s forensic analysis of a sick media. But what conclusions does he draw? He correctly identifies the crushing of the print unions in the Wapping dispute as a turning point, not just for print workers but for journalists as well.

Wapping

He says that Murdoch’s establishment of his new ‘fortress’ at Wapping in 1986, “broke the print unions and removed the final obstacle to the rule of the corporations ‘who thought greatly about commerce and casually about journalism’.” But then, reflecting popular prejudice, he makes the unwarranted statement: “Those unions were notorious for their greed and bad practices”.

There was nothing ‘greedy’ about the print workers. Through the force of their unions and many hard-fought battles in the past they had extracted from ruthless bosses favourable wages and conditions. They had established norms which other workers dreamed of and, moreover, hoped to attain in the future.

But the defeat of the print workers, together with the miners, discouraged millions of workers and, to some extent, still does today. Despite his misleading comments on the print unions, Davies admits: “But they were also the only force strong enough to resist the new corporate owners. And without them, the journalists’ union, which had always relied on the printers to stop the paper coming out when they were in dispute, lost its power too.”

This points up the crucial role of the working class as the leading force in industrial and social struggles, not just in the print unions or other industries but in general. It graphically underlines the dependency of other intermediary layers – although they might appear more ‘educated’ and ‘culturally’ advanced – and the majority of the middle class on the struggles of the workers. Moreover, historical experience has shown that journalists can be drawn into the whirlpool of social upheaval and move to the left, sometimes in a decisive fashion. Witness the radicalising effect on journalists of the Russian revolution – with John Reed as one striking example – or the Spanish, Chinese and Portuguese revolutions.

Upheavals in Britain, which loom, can exercise a similar effect on British journalists, especially as many are now subjected to the same neoliberal, brutal sweatshop conditions as workers in general.

The one weakness in this book is that Davies is reluctant to draw the conclusion that the media is in the service of ‘political power’, particularly that which defends the already existing capitalist system. He freely admits that the press barons of the past were “in love with political power” and the demands of the system. Lord Northcliffe used his newspapers to topple the Asquith government in May 1915 and “create another (led by Lloyd George in December 1916)”.

His brother, Lord Rothermere, infamously through the Daily Mail, cheered on the fascists in Germany and Britain in the 1930s. Lord Beaverbrook bluntly stated that, as owner of the Daily Express: “I run the paper for the purpose of making propaganda and with no other motive”.

Owners’ influence

Davies tries to argue, unsuccessfully, that the new corporate owners interfere far less than their propagandist predecessors. Proof of this, he says, is that most journalists “nowadays will tell you they have never written a story on the instructions, direct or indirect, of an owner or of any editorial placemen employed by an owner”. He misses the point that such ‘instructions’, are generally not necessary because most journalists have a censor sitting on their shoulders.

Max Hastings, editor of the Daily Telegraph under Conrad Black, confessed: “I’ve never really believed in the notion of editorial independence… I would never imagine saying to Conrad, ‘You have no right to ask me to do this’, because Conrad is… rightly entitled to take a view when he owns the newspaper”.

Andrew Neil, right-wing lickspittle of Murdoch and Thatcher, when he took over the Sunday Times, described Murdoch as “an interventionist proprietor who expected to get his way… Why should the owner not be the ultimate arbiter of what was in his paper?”

But the most crucial question raised by this tremendous book is the one posed at the end by Davies himself: ‘What is to be done?’ He shows that the Press Complaints Commission (PCC) is a toothless body incapable and unwilling to take on the press moguls in the declared interests of truth and objectivity. It rejects 90% of all complaints on ‘technical grounds’ without investigating them.

But his weakness is a harking back to an imaginary time when journalists wrote not to the agenda of the owners of the press but to the honest principles of journalism. It is true that there were some, such as The Times pre-Murdoch, which were journals of record, reporting events objectively, in the main to forearm the class it represented, the capitalists.

Leon Trotsky, one of the leaders of the 1917 Russian Revolution, once declared that The Times told the truth nine times out of ten, the better to lie on that crucial tenth occasion when its vital class interests were at stake. This was demonstrated in The Times’ stance in the 1926 general strike. In every major social confrontation since that has been the case. The difference today is that Murdoch’s Times, with the rest of the press, only rarely allows the truth to be reported.

This does not mean to say that there are not courageous journalists and commentators today who do their best to inform us of the truth, to seek to champion the oppressed, downtrodden and working class. But theirs is a muted voice compared to the past, with attempts to push them to the margin, as with the courageous likes of John Pilger, Robert Fisk, etc.

Davies places his hope in alternative sources of news, particularly on the internet. But he pessimistically adds: “In the real world, however, it is unlikely we will find any way of bringing the media back on track”. This begs the question whether it was ever ‘on track’? To paraphrase Karl Marx, the ruling ideas of any epoch are ultimately those of the ruling class. This is the real role of the media in capitalist society.

The solution ultimately is to create a real alternative. This means creating alternative, democratically controlled sources of information, particularly about the struggles of the oppressed, the activities of the working class, the labour movement and the trade unions. This means independent papers, hopefully in time radio stations, and demands for access to TV.

Omission

Davies says that one of the greatest sins of the media today is ‘omission’. He gives some examples of this but does not mention that there is no discussion of what is taking place in the workplace – the boiling anger of the working class, the deterioration in their conditions, etc.

This task will not be fulfilled by the present media. All strength to those conscientious journalists who seek, through the cracks that exist, to find a road to the truth and objectivity. But it will be by building up a powerful workers’ and socialist press that the real alternative to the ‘cancer-ridden’ media of Britain and the world will be created.

This must be accompanied by raising now the need for the nationalisation of the printing presses, television and radio, under popular management and control, as the most democratic means of overcoming the dictatorial stranglehold presently exercised by the press moguls and their acolytes.

This is not to suggest ‘state control’ of the press. We, the working class and the labour movement, do not want to take over the Sun, the Daily Mail or even the august Guardian. We oppose the state monopoly of news and information as existed in the Stalinist states of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

Similarly, we opposed the recent actions of Hugo Chávez against the right wing television station RCTV, which was used as a handle by the right to picture his government as taking a step towards dictatorship.

Socialist press

The real alternative is democratic working class and popular control of the press and media resources in general. This would not result in a monopoly for the government or one party but allow access to the media in proportion to political support.

Trotsky wrote 70 years ago, in relation to Mexico where the issue of press freedom and nationalisation was being discussed: “The real tasks of the workers’ state do not consist in policing public opinion, but in freeing it from the yoke of capital. This can only be done by placing the means of production – which includes the production of information – in the hands of society in its entirety.

“Once this essential step towards socialism has been taken, all currents of opinion which have not taken up arms against… the proletariat must be able to express themselves freely. It is the duty of the workers’ state to put in their hands, to all according to their numeric importance, the technical means necessary for this, printing presses, paper, means of transportation”.

Capitalism and Stalinism defend undemocratic control of the media by a minority. Socialism with democracy stands for taking the ‘production of information’ out of the hands of a minority to put it in the hands of a majority and allow full freedom of discussion.

Flat Earth News

by Nick Davies

Published in 2008 by Chatto & Windus

£17.99

Available from Socialist Books

PO Box 24697, London E11 1YD

Phone: 020 8988 8789.

Email: [email protected]