THE GREAT miners’ strike of 1984-85 was the longest lasting, most bitter industrial dispute of the second half of the 20th century in Britain and was undoubtedly the most widespread in its effects on society generally.

It was one of the most momentous events ever in British labour movement history and had a huge impact on virtually every subsequent industrial and political development.

Over 27 million working days were lost in strike action in 1984 (mainly amongst miners). Two miners, David Jones and Joe Green, were killed while picketing. 11,300 miners and their supporters were arrested and over 5,600 stood trial and more than a hundred were jailed, although 1,504 were released without charge. Striking Nottinghamshire miners had curfews and a pass system imposed on them – like the hated apartheid system in South Africa – which meant they were virtually under house arrest on occasion.

Seafarers were sacked and railworkers were victimised for taking solidarity action with the miners. Over 700 miners were sacked and not reinstated in their jobs.

The state benefit system was abused to try and starve the miners back.

In response to all of this, over £60 million was raised for the miners, according to the Guardian newspaper. Warehouses full of food and toys were donated to the striking miners and their families from trade unionists and supporters in Britain and internationally.

A huge network – an alternative welfare state in effect – started and inspired by the miners themselves and the miners’ wives support groups, mushroomed and spread across the five continents of the globe.

In particular the strike saw thousands of miners’ wives come to the forefront; not solely organising background assistance but going on picket lines and travelling throughout Britain and the world explaining the miners’ just cause.

Women played a vital role in the strike. Sue Alberry from Clowne, a North Derbyshire village with half a dozen local pits described how the local Women’s Action Group started from scratch to build this support: “Our group of miners’ wives and other local women gave out 300-400 food parcels every week until the end of the strike. When we needed to feed pickets, there was no electricity or hot water in our strike centre, but we were given camping stoves, gas lamps, tables and forms and we were soon cooking 200-500 breakfasts a day. We started a two shift-system – one week picketing, one week in the centre. A local shopkeeper gave us buckets of hot water from his shop, another gave us bread rolls. The butcher wouldn’t give us anything and his shop was boycotted for years afterwards.

“In the school summer holiday we supplied hot meals for the kids. We found clothes, prams and cots for babies born during the strike. At Christmas we organised a party at a local pub with a striking miner as Santa – all the kids got a small present. The hardest part was when they went back to work. We marched back with them, heads held high because we did what was right. I felt proud to have been part of this strike.” 1

This huge collective effort in backing the miners meant that Tory prime minister Margaret Thatcher did not get the short, sharp victory she hoped for against her old class enemy. And the events of the miners’ strike have left a legacy of bitterness and class hatred that has remained for decades to haunt the Tories.

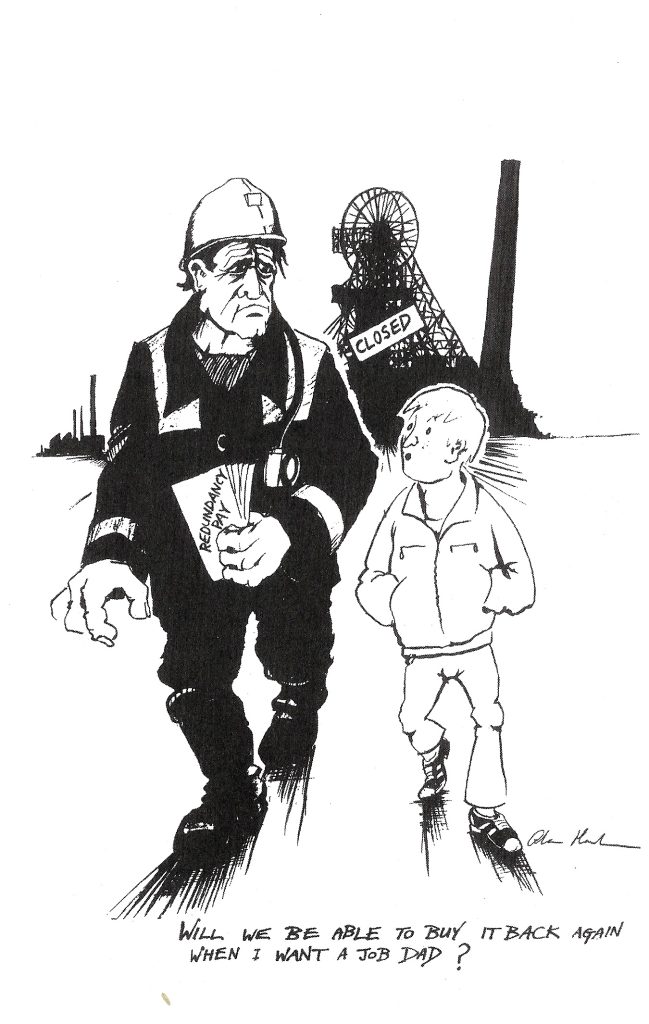

The Tories later admitted that it cost nearly £6 billion to win the dispute, which they saw as a political attempt to break the power of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). And from 1985-95 the Tories’ continued war against the miners cost at least £28 billion spent in destroying the coal industry through redundancy and benefit payments, keeping pits mothballed and lost revenue from coal. According to Dave Feickert, the NUM national research officer from 1983-93: “This is nearly half of the North Sea tax revenues of £60 billion collected since 1985.” 2

It was estimated that over £10 billion was spent switching coal-fired power stations to dual coal and oil use before and during the strike.

Thatcher and her cabinet were desperate for victory and prepared to go to great lengths – the police were openly used as a political weapon. Former Tory chancellor Nigel Lawson admitted that preparation for the strike was “just like rearming to face the threat of Hitler in the 1930s”. For the first time in a post-war national strike the police were brought out before the public’s gaze as an openly political arm of the state and an increased suspicion and lack of confidence in them has remained since. Agents provocateurs, spies and the army were also deployed.

MI5 and MI6 were involved. Shadowy right wingers like David Hart and Tim Bell, who were Thatcher’s undercover advisers during the dispute, have since boasted about their connections with the intelligence communities and the funding they received from big business. And former trade union leaders like Joe Gormley of the NUM and other union officials, it is claimed, were working for MI5, including Roger Windsor, who was chief executive of the NUM during the strike.3

Yet, despite the extraordinary lengths the Tories went to, by October 1984, six months into the strike, the future of Thatcher’s government hung in the balance – when there were less than six weeks’ coal stocks left. The proposed strike by the pit supervisors’ union NACODS threatened to close down all working pits in the Midlands at this time.

Former chairman of the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB), Sir Walter Marshall, spelt out what this meant: “Our predictions showed on paper that Scargill would win certainly before Christmas. Margaret Thatcher got very worried about that… I felt she was wobbly”. 4

lan MacGregor5, the Thatcher-appointed boss of the National Coal Board (NCB), was summoned to Downing Street and recalls Thatcher’s comments in his memoirs: “I’m very worried about it. You have to realise that the fate of this government is in your hands Mr MacGregor. You have got to solve this problem”.6

The Iron Lady melts

BUT IT wasn’t the determination of the ‘Iron Lady’ Thatcher or any other Tories that saved them – it was the trade union and Labour leaders. The union leaders claimed they couldn’t deliver support for the miners but the experience at rank-and-file level was that workers were ready to come out in support.

A poll even in the dying days of the strike, when it was clearly heading to defeat, showed that 40% of trade unionists still supported the miners and 35% – many of whom would have been in key sections that could have determined the outcome of the strike – were willing to take action.

Even at that stage, with the correct call and leadership, such support could easily have been built into a force of two to three million workers. This force could have taken the generalised solidarity strike action that may have staved off the miners’ bitter defeat and possibly even have brought victory.

Ned Smith, the former director of Labour relations at the NCB commented in a TV interview after the strike that the failure of the Trade Unions Congress (TUC) to deliver “total support” for the miners was the turning point in the attitude of the government.7

Some Left union leaders genuinely wanted to help but lacked the elementary tactics, strategy and confidence to do so. We commented at the time that unfortunately “the infection of new realism [the class-collaborationist rightward drift of the union movement] had even spread to the Left leaders”, who only gave the most general of calls for solidarity action with very little concrete being done in practice.

However, when the dockers came out in July, there was talk in Tory government circles of calling a “state of emergency”. And on a number of occasions, Thatcher personally intervened behind the scenes in pay negotiations, such as the railworkers and power workers, to increase their offer and ensure a second front didn’t open. Car workers, after years of being under the cosh of Thatcherite bosses, began to recover their confidence and were also given a generous pay settlement when they threatened action.

Miners still defiant – 20 years on

AMONGST many miners and their families and supporters there is still a huge pride in their battle from 1984-85 struggling so magnificently when such odds were stacked against them. But it still sticks in their throats to be told their struggle was doomed from the start and that they were only being used as pawns in an ideological battle between Margaret Thatcher and Arthur Scargill.

They were not, as right-wing electricians’ leader Eric Hammond insultingly described them: “Lions led by donkeys.” The miners’ strike was clearly not orchestrated by NUM leaders like Scargill, but started from below as a defensive struggle to stop the rundown of their industry and to preserve their communities.

Striking miner Dave Nixon summed up the mood of many young miners when he told a BBC documentary in 2004: “In February 1984 we were like a coiled spring ready to be triggered… Of course we knew it would be a long strike but we were willing to suffer the two months we thought it would take to convince the Coal Board that their arguments were unjust.”

The reality was that the national and area NUM leaderships knew what was coming – particularly with the build up of coal stocks – but were not certain about how and in what way their struggle would develop. Certainly, much of the leadership appears to have been caught off guard at the beginning of the strike, which produced a cautiousness and hesitancy in the early days which led to complications later on.

Even leading figures on the Left who were solidly behind the strike pessimistically concluded early on that the miners would not win. In Tony Benn’s diary entry for 5 May 1984 he wrote: “It looks as though the miners cannot beat the government.” 8 He did, however, predict a long strike.

Yet, once the strike started it developed its own logic. It was clearly seen by the miners and their supporters in the wider working class, as well as by the Tories and the ruling class, as a battle that had to be fought to the finish. On a number of occasions during the dispute the government wavered when it saw partial strike action in support of the miners from other sections of workers.

The class struggle is not decided in advance like a mathematical formula. It can only be decided in the course of struggle itself and the miners understood that – even if they felt the odds were against them. It is better to fight and aim to win rather than go down to defeat without any resistance.

The support the miners’ battle engendered showed that the working class was massively with them – even if most of the leadership of the workers’ organisations were not.

Labour leader Neil Kinnock only visited a picket line once during the dispute nearly ten months into the strike. For most of the time before that he had hypocritically and equivocally claimed to support the miners whilst repeatedly condemning picket line ‘violence’.

Whilst some former miners’ leaders and the majority of the trade union and Labour leaders have moved far to the right since the strike – almost occupying a parallel universe – the miners who took strike action have not had regrets, nor repudiated their stand.

Joe Owens, a Scottish miner who was a Militant supporter during the strike, summed it up in a book he wrote marking the tenth anniversary of the strike: “I feel privileged to have fought it. I wept when it ended and on the day three years later when they shoved us out on the stones with shitpence compensation; and I wept again in 1992 when another 30,000 men and their families faced what men I knew had faced. Everything to do with the experience is still raw and ten years later the rage is still with me. I think it always will be.” 9

Other miners still feel the same 20 years on. One such is Brian Wilson of Brampton, near Cortonwood: “I would go through it again… it was the notion of comradeship, of them against us, standing back to back… everybody were together. It were a thing I wouldn’t have missed.” 10

His wife, Anne Wilson showed what a revolution in consciousness the strike meant for the women who got involved: “A lot of the women who supported the strike had never gone out to work; they just looked after the family and that were the way the miners wanted it to be. Then suddenly they came into their own. You see, the women found a voice, they found education and work – and that’s something they never lost.” 11

Yet, it was about much more than the ‘spirit of 1984’. The miners’ strike became an ideological battle about the future direction of society. Militant warned at the time that the Tories wanted to reduce mining and trade unionism to a “mere memory”. They have since virtually annihilated the coal industry and undermined manufacturing industry to a point where even sections of the ruling class can see that such a collapse is not in the long-term interests of British capitalism.

Mail on Sunday columnist Suzanne Moore put it succinctly enough: “What their strike represented to us was a set of values worth fighting for. It was never simply about pay. It was about the threat Thatcher’s free-market philosophy meant to their way of life, to their communities, to the very idea of trade unions.” 12

Yet, the miners’ struggle ensured that the imprint of militant trade unionism, though weakened, remained strong enough to survive the difficult period of the 1990s and is currently resurfacing.

It would take dozens of books to recall all the sacrifice and heroism of the miners’ struggle and the detailed events of 1984-85. But as well as the fighting tradition of the miners we need to pass on to a new generation the lessons – political, strategical and tactical – from the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

NOTES

1 From The Socialist, issue 337, 13 March 2004

2 The Guardian, 11 February 2004

3 For a full account of Windsor’s role (along with that of Hart and Bell and MI5) see The Enemy Within, Seumas Milne, Verso, London 1994 and 2004

4 Interviewed on a Channel Four Dispatches programme in 1994

5 According to Paul Routledge, after Tory cabinet minister Lawson persuaded Thatcher to give Gormley a peerage he “maintained close links with the former electricians’ union boss Frank Chapple, ‘who detested Scargill and was at one with me in longing for a Coal Board management capable of standing up to him”.

“Chapple advised him to get someone who was not afraid of Scargill. Most businessmen said they weren’t but in their hearts they were, he told Lawson after a dinner a deux. ‘The Chapple test was one good reason why I went for MacGregor,’ he wrote.” (Paul Routledge, Scargill the Unauthorised biography, Harper Collins 1993, p132)

6 Quoted in The Enemies Within, Ian MacGregor with Rodney Tyler, Fontana 1985, p281

7 Quoted in Peter Taaffe, The Rise of Militant, Militant publications, London 1994

8 Quoted in Paul Routledge, Scargill the Unathorised Biography, p147

9 Miners 1984-1994, A Decade of Endurance, edited by Joe Owens, Polygon, Edinburgh 1994, p4

10 Brian Wilson quoted in Observer Magazine, 1 February 2004

11 Anne Wilson quoted in Observer Magazine, 1 February 2004

12 Mail on Sunday, 7 March 2004