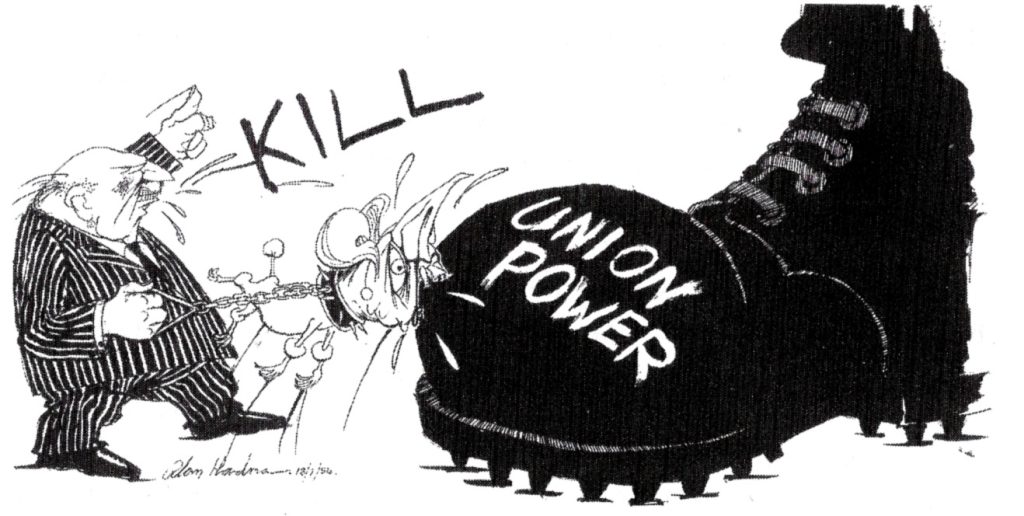

THE SEEDS of the 1984-85 miners’ strike were planted years before the strike started in March. The defeats the miners inflicted on the Tory government in 1972 and 1974 represented a political earthquake that resulted in Ted Heath’s removal from office in February 1974. Key strategists of the ruling class determined that never again would a strike or trade union action be allowed to determine the fate of ‘their’ government. In particular they decided that the power of the miners, along with other unions, needed to be smashed – even if this meant the destruction of whole sections of British manufacturing.

Coal Board boss Ian MacGregor had announced in the autumn of 1983 that he planned to close 20 pits and axe 25,000 jobs in the mining industry. But it was when the proposed closure of Cortonwood colliery in south Yorkshire was announced on 5 March, that a walk-out of Yorkshire miners was provoked which rapidly began to escalate. The NCB area director announced Cortonwood’s immediate closure without going through the accepted pit closure review procedure, in order to meet MacGregor and Thatcher’s imposed cut in production levels. This was seen by the rank-and-file miners as the gauntlet being thrown down.

A few other pits in Yorkshire had already walked out. Within days most of the coalfield was strike bound and the area became the militant hub of the strike, sending out flying pickets to other areas.

Since the Tories’ election in 1979, 47,000 mining jobs had been lost and 48 pits had been closed. Even after Arthur Scargill’s election as NUM president in late 1981 over 20,000 mining jobs were lost and 21 pits closed.

However, during this time all pit closures were subject to the review procedure. This involved all mining unions being involved before accepting closure on the grounds of exhaustion or safety: alternative jobs were then provided for those miners wishing to remain in the industry. Mining is an extractive industry and inevitably some mines will close through natural exhaustion of mineable coal.

But the threat to Cortonwood was of an altogether different character from all other pit closure proposals. The shady hands of MacGregor and Thatcher were behind this attempt at a more rapid downsizing of the industry.

The decades of decline

AFTER THE coal industry’s nationalisation in 1947, there followed decades of a slow, haphazard decline in the size of the industry and the number of men (and a few women) employed in and around the pits. In 1948 over 600,000 worked in the industry, by 1984 this was just 182,000.

On average, between eight to ten pits closed every year in this period and more pits closed under Labour governments than Tory ones. However, Thatcher’s Tory government was going for a much bigger cull.

In the post-second world war years, certain elements of workers’ control over issues like health and safety and hiring and firing had developed in the nationalised industry, particularly at local level through the efforts of the NUM. At a national level, however, despite having Communist Party (CP) members as NUM general secretary like Arthur Horner (1945-59) and Will Paynter (1959-68), the NUM’s reputation for militancy was based on past struggles.

This period of CP rule saw no official strike action taken by the union against gradual pit closures and a correspondingly serious decline in miners’ living standards until the 1970s. The NUM, which was formed from the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) in 1944, had never organised national strike action on any issue until the 1972 strike over pay.

The state of labour relations in the coal industry at the time is revealed by a statement by Lord Robens, NCB chairman, on the decisive pro-management role of Will Paynter in the 1964 national wage negotiations: “Paynter was still a Communist, which made his speech all the more remarkable, but his devotion to the union and the men whose well being was his responsibility, as always, came before his party’s affiliations… He told his hearers he accepted the board’s offer of nine shillings and sixpence per week [about 50p a week] on the minimum was the most the industry could afford… Paynter saved the day.” 1

In 1948, miners’ wages were 29% above the average pay of manual workers. By 1960 they were only 7.4% above and by 1970 they were 3.1% below the average. The introduction of the national power loading agreement (NPLA) in 1966 helped overcome some of the problems miners had faced in getting paid a proper national rate for the job by introducing a standard wage structure for the industry.

In previous bonus scheme deals workers were paid according to how much they produced without taking into account the hours worked or geological complexities at a pit. The NPLA made sure miners no longer faced the incessant battles over their rate and for once they knew how much they would be paid every week.

Resurgent tide of struggle

THERE HAD been a resurgence of the traditional miners’ militancy below the surface in a number of key coalfields in the late 1960s. In Yorkshire, a traditionally right-wing area of the union, the creation of the Barnsley Miners’ Forum in 1967 led to the development of a new generation of left-wing leaders emerging from the rank and file – foremost among them was Arthur Scargill.

The Barnsley Miners’ Forum was to play a crucial role in organising successful unofficial industrial action on pay and conditions in the 1960s, which developed the methods of flying pickets and mass picketing used so successfully in 1972 and 1974.

The reputation of the miners as the militant brigade of guards of the labour movement was won through its heroic struggles at the start of the 20th century and their nine-month struggle and defeat in 1926.

The miners retied the knot of history as a militant class-struggle union in the 1970s – a period of heightened industrial and political action – where they were at the forefront of workers’ struggles, organising solidarity and inflicting the humiliating defeat of Heath.

The rising curve of industrial militancy in the early 1970s is shown through the number of days lost of all workers in strike action:

| 1970 | 10,908,000 days lost | |

| 1971 | 13,589,000 days lost | |

| 1971 | 23,923,000 days lost |

The figure for 1972 has only been surpassed three times in the recorded history of strike action in Britain: in 1926 the year of the general strike, in 1979 through the so-called winter of discontent strike by public-sector workers against the Labour government’s pay freeze and in 1984 itself (27 million days) because of the miners’ strike.

From 1969-70 onwards a series of industrial demonstrations and strike movements against the industrial relations policies – an attempt to restrain the growing influence and power of trade unions amongst the working class – of first the Wilson Labour government of 1964-70 and then the Heath Tory government of 1970-74 had greatly radicalised and politicised huge swathes of trade union activists and workers generally.

Mass demonstrations, strike movements and even a threatened one-day general strike took place against the Heath government’s anti-union legislation. In particular, action against the jailings of the Pentonville Five London dockers and the Shrewsbury Two building workers in 1974 under the Industrial Relations Act and the occupation of Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, showed the heightened consciousness and militancy of workers at that time.

Into this arena stepped newly confident and militant miners in 1972 winning a huge victory for higher wages, which helped erase the bitter memories of the defeat of 1926. The miners gained victory because the NCB and the government were unprepared for the strike, reckoning that a right-wing national leadership could avert the threat of action and that the post-war consensus about managing the industry would continue.

The flying pickets

ANOTHER KEY factor in the strike was the more widespread development of flying pickets and mass picketing. A pivotal point was the closure of the gates at Saltley coke depot – a coal storage depot for the foundries and industry in the Midlands. On 10 February 1972, 10,000 miners, engineering and car workers descended on Saltley Gates – as well as strike action being taken that day by over 100,000 workers in the area after Arthur Scargill, president of the Yorkshire miners at the time, addressed mass union meetings. This then forced the police officer in charge to demand the closure of the gates.

Miltant, the forerunner of the Socialist Party, played a significant part in this action: “Militant supporters in Birmingham had played a key role in tipping off the NUM pickets in Birmingham that Saltley Gate was being used as a collecting depot for ‘scab coal’.” 2

Then the miners’ action really began to bite and successfully ended decades of divisions over pay between pits and areas.

These tactics were again put to use in the industrial action of 1974, following an overtime ban from the end of 1973, although on a lesser scale than in 1972. The Heath government, still licking its wounds from 1972, was more consciously trying to take on the miners and break them this time round.

However, Heath had still not prepared in the same way as Thatcher was to prepare a decade later. The miners had instituted an overtime ban before strike action, which was coupled with electrical power workers refusing to work around the clock. This alone was enough to bring in a “state of emergency”, with petrol rationing, power cuts and the infamous three-day working week.

The Times newspaper, then seen as a more authoritative voice for the interests of British capitalism said: “We cannot afford the cost of surrender”, outlining an intent for a fight to the finish with the organised working class.

The Times also raised the shadowy threat of more dictatorial measures to beat the miners’ action saying that “the only remaining choice is to impose a policy of sound money at the point of a bayonet.”3 The moves towards an authoritarian solution were constantly being explored behind the scenes during this period.4

With an effective two-day-a week lock out declared on the working class, Prime Minister Heath then called an election in February 1974 where he asked ‘Who rules the country?’ The answer he got was that it was not him or his Tory Party. In one of the most polarised ever general elections – with the miners’ strike ongoing – Heath was turfed out of office. The success of flying pickets and mass picketing was to form a key part of the psychology and preparations of militant miners in the run-up to and during the 1984-85 strike.

But the ruling class learnt lessons from the strikes of 1972 and 1974 and made preparations accordingly for the brutal class war they conducted in 1984-85. The NUM leaders were aware of the preparations made by the Tory government elected in 1979 (through the Ridley Report and other measures, of which more later, that represented a qualitative change in the thinking of sections of the ruling class). But they were still reliant on the tactics of 1972 and 1974 to win their next strike.

It was not that the tactic of flying pickets and mass picketing were wrong or inappropriate. However, because of a number of fundamental differences they could not be the sole means of winning victory in an all-out bitter political dispute that 1984-85 was to become.

One factor working against a cohesive national struggle on either pay or pit closures was the effective imposition of divisive bonus payments in 1978, despite a national ballot voting against it by 55%. The Left successfully argued against reintroducing the scheme, which was hated in many areas, because it set miner against miner and pit against pit. The right-wing areas and national leadership, including NUM President Joe Gormley defied a national conference decision against the scheme and tried to subvert it by gaining a High Court ruling to hold a ballot.

When the ballot went against them they declared it null and void. Then the Left challenged this constitutional fraud at the High Court where Mr Justice Watkins said: “The result of a ballot nationally conducted is not binding upon the National Executive Committee.”

Incredibly, this was a ruling the right wing chose to forget in 1984.

And it opened the floodgates for the incentive schemes. This meant once again that a miner in one pit could earn only £6 a week in bonus payments whereas a miner in an allegedly more productive pit nearby could earn over £40 a week. The variations between areas were further enhanced by the differential bonus payments. Such divisions were to be a factor in later national pay ballots and indeed in the 1984 strike.

The Tories regroup and prepare for showdown

EVEN BEFORE its election in 1979, the Tory Party, egged on by the ruling class who wanted to curb the effective power of the unions, made industrial and political preparations to take on the miners. Their reasons were many fold, with revenge not the least amongst their motives. But, as has been subsequently shown, the Tories were using their war against the miners to attempt to weaken and break the power of organised labour. They were willing to carry through a deindustrialisation of key sectors of Britain where working-class opposition to the Tories had been strongest.

Coupled with this was the attempt to smash local democracy in councils like Liverpool and Lambeth, which opposed – successfully for a period – the Thatcher government’s plans. These meant the impoverishment and destruction of parts of inner-city Britain through a massive programme of cuts in public spending as part of their monetarist programme.

The key elements in the Tories’ preparations for the events of 1984-85 were the implementation of the Ridley Report proposals, which was ‘leaked’ in the Economist in 1978. This infamous report was written by Nicholas Ridley who was later to become a Tory cabinet minister and Lord. It proposed the following:

- A building up of coal stocks to see power supply last throughout a lengthy miners’ strike.

- The increasing use of private, non-union haulage companies to carry coal.

- Some power stations were switched to dual coal and oil burning.

- A massive tooling up and increase of police powers was to be combined with more draconian civil (anti-union) and criminal laws during the strike.

The Tories did all this and more with a vengeance. From 1980 to 1983 coal stocks were built up from 37.7 million tonnes to 58 million tonnes. And in 1981 the Central Electricity Generation Board was asked by Sir Donald Maitland, Permanent Secretary at the Department of Energy, to prepare a contingency plan to cope with a miners’ strike. It was ready within a few months.

This followed on from the Thatcher government’s humiliating climbdown at the hands of the miners in 1981, when South Wales miners’ bold and determined action against pit closures began to spread throughout the British coalfields. The Iron Lady was forced to retreat without using any of her newly established legal powers, like the Employment Act.

The miners’ victory in 1981, after the setback of the steel strike in 1980, gave confidence to other groups of workers taking industrial action but it was clear, as Militant warned at the time, that this was a temporary, tactical retreat. Thatcher and the ruling class would come back at a later stage, if they were allowed to, with further attacks.

Chronic underfunding

THE PITS, however, were also made to look increasingly uneconomic and liable to closure during this period by a process of starving the industry of funding. There was a continual rigging of the NCB accounts – to portray the industry as a loss-making operation – and an increasing use of the discovery of geological problems at pits by a new more hardline NCB management now headed by Ian MacGregor. (5)

The NCB was charged over £100 million in interest to store the millions of tonnes of coal that was stockpiled. Additionally, British coal had the lowest level of state subsidy in Western Europe.

| West Germany received £8.60 subsidy per tonne | |

| France received £17.20 subsidy per tonne | |

| Belgium received £17.70 subsidy per tonne | |

| Britain received £3.20 subsidy per tonne |

Militant argued for the same level of subsidy to be applied to the British coal industry, as opposed to the argument put forward by the Communist Party and Labour Left that there should be controls limiting the import of coal from other countries. Import controls, Militant argued, would set miners in one country against another and would sow the illusion that there could be a ‘national’ solution to the looming crisis in Britain’s coal industry at the expense of other miners abroad.

For a long time before the strike, and during it, Militant argued that whilst it was necessary to campaign against pit closures there also needed to be a socialist plan of production for the industry and a socialist, integrated energy policy. These demands were first featured in a Militant NUM programme for action produced as a pamphlet in late 1977.

- It was clear then that at some stage there would be conflict over the future of the coal industry. The Plan For Coal drawn up by the NCB in 1973 had envisaged a much larger ‘market’ for coal than actually transpired in the early 1980s. In response to the threatened contraction of the industry we argued in the pamphlet for:

- Removal of the Coal Board’s debt

- Open the books; no phoney accounting; scrap the interest charges

- End competition among nationalised industries

- No redundancies; fight all closures except on grounds of proven exhaustion or safety as determined by the union

- Work or full pay; alternative work at equivalent rates and benefits

- Combat the NCB propaganda on the need to stockpile coal

- For workers’ control and management of the coal industry

- For the nationalisation of all private concerns in the fuel industry under workers’ control and management

- For the setting up of a national fuel corporation

- For a socialist national fuel policy (6)

Thatcher insisted at the time that “Marxists wanted to defy the law of the land in order to defy the laws of economics”. But in her memoirs she revealed: “The coal strike was always about far more than uneconomic pits. it was a political strike.” 7

During the strike Left-wing Oxford University economist, Andrew Glyn produced a pamphlet, commissioned by the NUM, which showed when many of the NCB’s false overheads were stripped away the coal industry was not “insolvent” as the Tories claimed and “the production of coal in 1983-84 more or less covered its underlying costs of production and financed the industry’s investment.”

He also pointed out that when you added the devastating economic costs of shutting down pits then “there is not one single pit whose closure would benefit government revenue”. He concluded that “under present circumstances there is no economic case whatsoever for pit closure before exhaustion of mineable reserves.” (8)

The warning signs

HOWEVER, ALL of the Tory preparations for a showdown with the miners would have come to nothing if the Thatcher government had not been prepared to play its political hand more astutely than the leadership of the Labour Party or the TUC.

Thatcher and her ruling clique had gained confidence in the run-up to the 1984 strike following their ‘success’ in the Falklands/Malvinas conflict and winning the 1983 election against a Labour opposition weakened by the split and temporary rise of the Social Democrat Party – a right-wing breakaway from the Labour Party.

However, this combination of ‘successes’ would have not been enough, in themselves, to have given Thatcher the necessary confidence to take on the miners; especially given that Arthur Scargill had been resoundingly elected president in 1981 with over 70% of the vote.

Before Thatcher took on the miners a number of other key factors were to slot into place.

After the 1983 election defeat, Labour and trade union leaders, including the newly elected Labour Party leader, Neil Kinnock, advocated a policy of ‘new realism’. This was a code for retreating in the face of the class enemy without firing a shot in retaliation. Politically this was the beginning of a long rightward march which has led to Blairism, the complete transformation of Labour into an openly pro-capitalist party.

The philosophical ‘justification’ for new realism was that the defeat of Labour in the 1983 election, with one of the most radical manifestoes in its history (falsely dubbed the longest ever suicide note in history by right-wing Labour MP Gerald Kaufman). This implied that socialist ideas were no longer popular and that accommodation with the bosses and the Tories had to be sought by the trade unions. Politically, arguments like those of CP academic and author Eric Hobsbawn, arguing that the class composition of society was changing, the manual working class was dwindling and consequently the old class notions of solidarity etc were no longer applicable, were echoed by Neil Kinnock and his entourage.

Roy Hattersley, who now bemoans the rise and effects of Blairism, was an early advocate of ‘new realism’ and breaking the union link. In January 1984 when deputy leader of the Labour Party he told a Fabian Society lecture that “trade unions are a diminishing force in British political and industrial life… the dependency of the party on them is something on which I do not believe we can rely in the future as we could in the past.” 9

How wrong the ideas and practice of ‘new realism’ were would soon be shown by the Warrington NGA printworkers’ struggle against Stockport Messenger Group owner Eddie Shah’s attacks on the union in December 1983. Despite determined action by the printworkers and their supporters the Warrington dispute’s ultimate defeat was to eventually prove the green light for the Tories to attack the miners.

It was the official policy of the TUC at the time to defy the anti-union laws and to defend any union that was threatened by them. This had been passed at a special conference in Wembley 1981.

From the weakness displayed by the TUC leaders during the Warrington battle, the Tories concluded that the union leaders would not be able to deliver solidarity action if the capitalist class launched a bitter and brutal offensive against the miners.

The Warrington dispute was the first time that the Tories’ new anti-union laws were tested against the trade union movement. The NGA faced sequestration (seizure of its assets) after defying a court judgment of a £50,000 fine against the union. The nightly mass picketing at the Warrington plant saw the first appearance of the new beefed-up police forces under the Tories. Workers who had come from all parts of the country to support the printers were consistently and brutally attacked by the police.

Militant said at the time: “The gloves are off. The ruling classes are out to destroy the print union the NGA… The Tories have declared war.”

The paper also demanded that the TUC should deliver on its commitment to general strike action. Despite it being the policy of the TUC, the call never came, apart from through Arthur Scargill.

The recently elected president of the NUM called for a 24-hour general strike at a meeting of 500 miners, rail and steel workers in Birmingham and argued that the TUC and Labour Party should show the same dedication and commitment to the NGA and our class as the Tories show to their class “including the organisation of the most massive picket ever seen.” (10)

The strike could have been a famous victory, if the determination of rank-and-file workers who participated on the picket lines and supported the NGA had been matched by the union leaders on the TUC general council.

We called for an all-out printers’ strike when the union was fined £650,000 and faced writs for damages of over £3 million from newspaper owners. Print bosses, like the notorious Robert Maxwell secretly approached Stockport Messenger Group owner Shah at one stage to settle, because of the fear of where the workers’ struggles were leading.

Maxwell is alleged to have said: “God help us all” at the looming possibility of an all-out strike; an indication that the balance of class forces was still in the workers’ favour at that stage.

But the right-wing TUC leaders abjectly gave in to the Tories’ anti-union laws, urging the NGA and other print unions to stay within the law, and in so doing seriously undermined the power of the organised working class to resist the bosses’ attacks.

However, the Left in the unions also had to take on board the lessons and some responsibility for the eventual debacle at Warrington. Militant argued at the time: “The TUC general council, with its inbuilt right-wing majority, does not reflect the true balance of industrial power within the movement. The Left leaders of the TUC, therefore, those who supported the NGA must now be prepared to organise outside the framework of the TUC.” (11)

Shortly afterwards in an act of outright provocation, civil service trade union membership was banned at the government monitoring/spying centre GCHQ in Cheltenham; ostensibly on the grounds that their union membership threatened national security.

Again the union leaders meekly accepted the emasculation of union rights at GCHQ. They organised some token demonstrations and a day of protest involving over one million workers, but it was primarily an exercise in letting off steam.

And then the majority of the union leaders scurried away from the prospect of class war and buried themselves deep in their daily routines and the illusory hideaway of new realism.

Thatcher and the Tories were, however, just getting into their stride in practising their exceptionally brutal version of class war and were preparing to take on the miners in a once and for all showdown.

But, given the glaring weaknesses at the tops of the union movement, how ready were the miners and their leaders for what turned out to be the longest and most bitter industrial dispute in British union history?

NOTES

1 From the Communist Party of Great Britain since 1920, p153, by James Eadie and David Renton. Palgrave publishers, 2002

2 The Rise of Militant, Peter Taaffe, Militant Publications, London 1994, p57

3 This editorial essentially was arguing for the economic policy of monetarism – the linking of money supply to the country’s Gross Domestic Product –, which the Thatcher government was to bring in with a vengeance in 1980-81.

4 Lord Mountbatten and former Daily Mirror owner Cecil King for instance were discussing the possibility of a coup against Wilson’s Labour government.

5 Ian MacGregor was the asset-stripper who had recently downsized the steel industry, butchering capacity, closing steelworks and sacking tens of thousands of steel workers. He had also been deputy chairman at British Leyland and was instrumental in the sacking of Derek Robinson – Red Robbo – the CP union rep who had been leading the fight back against the Edwardes plan to downsize the company.

6 Militant issue 701 also carried a centre-page article outlining socialist plan for the coal industry

7 Quoted by Larry Elliot, The Guardian, 2 March 2004

8 The Economic Case Against Pit Closures, NUM, Sheffield 1984

9 Militant, issue 682, 13 January 1984

10 Militant issue 679, 12 December 1983

11 Militant issue 680, 16 December 1983