ALL STRIKES start hesitantly. For trade unionists and all working-class people, contrary to the popular tabloid myth, being on strike is not a normal way of life. It involves a huge shake up to the daily routine, the uncertainty of being without income and possibly losing your job as a result of the action. For all workers, taking striking action is always a last resort, rather than being seen as inevitable.

While the best union activists always hope for the best and prepare for the worst, even they would be the first to admit that they never fully prepare for strike action.

The innovativion and determination often associated on a broad scale with large sections of workers on strike tends to come as the strike gains momentum rather than at the beginning.

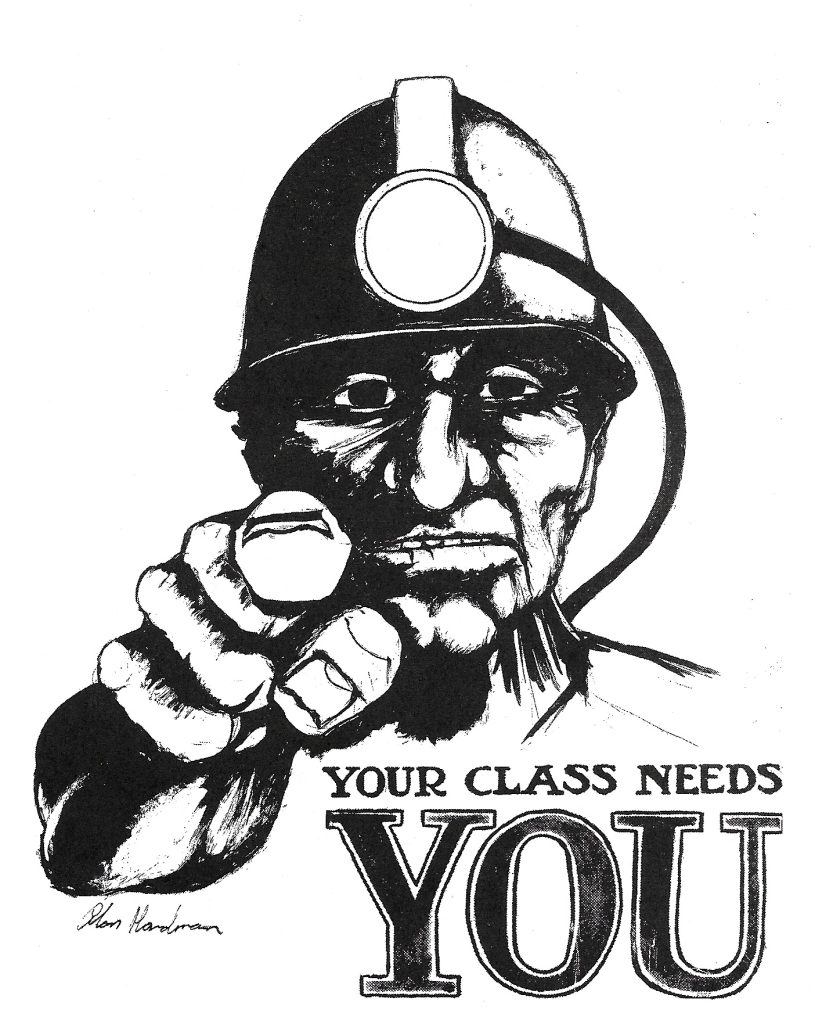

The miners at that time were one of the most experienced and organised groups of workers when it came to threatening or taking industrial action to defend their interests. They were meticulous in their preparation both in terms of political propaganda and many practical aspects of their action. Inevitably, however, there is always a certain rustiness, even amongst the most experienced union activists when strike action starts.

The 1984-85 miners’ strike, however, started more chaotically than many would have expected – especially given the clear signals that had been emanating from the Tory government and the new regime of NCB boss Ian MacGregor.

Left win control of NUM

THE START of the 1984-85 strike should have found the miners in a relatively strong position. For the first time in many decades the union had a left-wing president, vice-president and left-wing general secretary.

Peter Heathfield, from North Derbyshire, had been elected general secretary only a few months before the strike, to replace the retiring Lawrence Daly. Although securing only a narrow victory over right-wing area official John Walsh, Heathfield had explicitly campaigned against the threatened job losses in the industry and in support of the overtime ban, supported by over 75% of miners.

But Militant warned at the time “escalation of the dispute, to be effective must be before spring.”1 This was in response to those on the Left who argued that the overtime ban could go on beyond the summer, already tensions were building up in some of the coalfields.

Communist Party member Mick McGahey had been the vice-president of the union from 1973. Also, the Left had an outright majority of 13-11 on the union’s national executive.

However, that Left leadership had suffered a number of defeats (particularly in three ballots for industrial action on pay and pit closures since Arthur Scargill became president) in the run-up to the start of the strike in March 1984.

Generally, Left areas such as South Wales, Scotland, Kent and Yorkshire recorded majorities for industrial action for better wages, against pit closures and against the introduction of the incentive bonus scheme; forced through undemocratically by previous president Joe Gormley and the right wing.

Whilst there had been big votes against action in the areas like Notts and the Midlands that had generally benefited most from the bonus scheme – enough to tip the balance against national action – the votes against action had decreased at each ballot.

Peter Heathfield, though, only a few weeks before the strike told a joint LPYS/North Derbyshire NUM meeting that he doubted whether the younger generation of miners, who had big mortgages and took foreign holidays, would go on strike.

But it was the determined resistance of the younger miners especially, as the strike started, that developed the strike’s momentum. This time there was no escape route for a younger generation: moving on to another pit when yours closed was becoming more difficult as was the possibility of finding jobs outside the mining industry.

And the miners’ action especially struck a chord amongst younger people: “At Port Talbot steelworks nearly 200 young people from local schools and tech colleges joined a mass picket [early on in the strike]. The headmaster ordered the pupils back to school but as one told the police who tried to bully them ‘I’m furthering my education – I’m learning to be a picket because it’s the only job I’ll get round here.” 2

Former Tory cabinet minister Norman Tebbit revealed in 1992, how worried the Tories were by the threats of miners’ strike action in 1982 and 1983. He said that the 1984 strike had been a “close run thing” and 18 months earlier the miners would have almost certainly triumphed.3

It is an unfortunate irony of history that until March 1993 there had never been a successful NUM ballot for industrial action against pit closures. All successful ballots had been on pay. One reason for this lay in the NUM’s structure, which gave enormous power to area union officials. On issues like pay there was a general national agreement, but pit closures affected some areas more than others.

In 1983 the South Wales area took strike action over the threatened closure of Tymawr/Lewis Merthyr, which had been endorsed by the national executive under Rule 41. South Wales miners then went to other areas such as Yorkshire but found them hesitant about taking action. When a national ballot was called, pits in other areas which had started to come out returned to work while voting took place.

They were then subjected to the most fierce capitalist propaganda and this resulted in a 61% vote against action. This caused some confusion and bitterness among South Wales miners at the start of the 1984-85 strike.

This was taken as another green light by the Tories for them to look at a larger scale pit closure programme and take on the militancy and power of the miners.

Weakness of the NUM Left

THE OLD Left leadership of the union in many areas, and even the new Left in areas like Yorkshire, had to a degree been partially infected by the virus of new realism and were beginning to lack confidence in the ability of workers – even the miners – to prosecute a successful struggle.

Just weeks before the strike, for example, the Left leadership in Scotland, dominated by the CP and its fellow travellers, had given mixed signals on pit closures by postponing action for three weeks over the threat to close Polmaise colliery, near Stirling. The CP-dominated Scottish NUM executive eventually told local NUM officials to go it alone in their efforts to save the pit.

Polmaise, like other pits, could have been an issue that sparked a national strike. Certainly all the combustible material was there – the surrounding areas had 25%-40% youth unemployment rates and there was an angry mood, which was dissipated by the CP-led Scottish area NUM.

Fallin Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS), for example – led by local Militant supporters – organised a public meeting on the issue. With over 70 attending, local NUM officials said that a geological fault at the pit could be easily cleared within five weeks, opening up a coalfields, which could guarantee work at the pit for 30 years.

At the meeting a young miner said that in the previous three years he had been at four pits and at each one he had initially been promised 20 years’ work but each one had subsequently shut down very soon.

But at Polmaise the area leadership acted as a brake on the young miners, and unfortunately perhaps there wasn’t a local leadership prepared to push their area executive into taking action. By contrast, in Cortonwood a few weeks later the miners came out by themselves and forced the area executive to endorse their strike. Yorkshire miners then moved to picket other coalfields.

The federal structure of the NUM meant that each area had a high degree of autonomy and there was a long tradition of areas organising local action against pit closures, and then successfully picketing out others as South Wales had done in 1981.

However, whatever the mood of the rank-and-file miners, the area and national leaderships were still smarting from the previous ballot upsets.

Notwithstanding the courage and determination that was shown throughout the strike and after by the NUM national leaders, Arthur Scargill and Peter Heathfield, the beginning of the strike saw them caught off guard. Many NUM leaders had the perspective of the overtime ban, which had been solidly endorsed in a national ballot, continuing until the autumn of 1984 and then taking strike action.

Although ballots for industrial action against pit closures and on pay had been defeated, there had been an increasing vote for action on pay in all areas on the last ballot before the strike. Taking all these factors into consideration the Tories, through their henchman MacGregor, probably thought that the time was right for a pre-emptive strike in March 1984.

Lack of confidence

THE BALLOT defeats and lack of action in the previous year definitely caused some Left NUM leaders to lack confidence about strike action developing, even as the majority of Yorkshire miners – the biggest and strongest area of the union – came out.

The South Wales NUM leadership, for example, was traditionally one of the most militant. When its leadership recommended strike action in support of Yorkshire, it found that a majority voted against them at report back meetings at Lodges (local branches).

Only the decisive actions of miners like Tyrone O’Sullivan and South Wales NUM executive member Ian Isaac, turned around a situation where miners had initially voted not to come out in support of Yorkshire miners.

lan Isaac, then Lodge Secretary of St John’s NUM and a member of the South Wales NUM executive from 1983-87, has summed up (in an unpublished memoir) the unpreparedness of some of the left NUM leaders in the area. lan notes that when the closure of Cortonwood colliery was announced, which sparked the 1984-85 strike, there “was a hesitancy on the part of South Wales miners to be seen yet again as the ones to come out first. They also remembered the lukewarm reception they had the previous year when attempting to convince Yorkshire and other traditionally militant areas to join them on strike against pit closures.”

South Wales turns around

BECAUSE OF this confusion and caution the strike got off to an unsteady start. Although Kent came out more or less straight away, in Scotland and South Wales it took more persuasion to convince miners that this was the big one. In South Wales it took four days from Friday 9 March to Monday 12 March to clarify the strike decisively in action.

On 9 March the South Wales NUM executive recommended at a special conference in Hopkinstown that the South Wales lodges should support the strike action that had started in Yorkshire and Scotland – only five out of 45 lodges voted against.

Amongst the general public of South Wales at that time there was a general recognition that a battle against closures was inevitable and everyone rallied behind the miners. For instance, sales of the Militant rocketed upwards after the first few days of the Yorkshire miners being out and in anticipation of a national strike.4

But, the traditional loyalty of South Wales miners to their leadership may have been taken for granted by some of the area’s leaders and a more uncertain, uneasy mood had crept in amongst some of the miners, the older generation in particular.

At St John’s pit in Maesteg, there was a mixed and polarised mood at the first report back from the area conference. There was a two to one vote against strike action at a meeting on 10 March.

The younger miners – who had most to lose through mass redundancies – were furious and the whole of the Lodge Committee threatened resignation, although the Lodge committee leaders (three of whom were Militant supporters) convinced them not to resign but to stand firm.

Many of the older men had been initially lured by the enhanced redundancy packages of over £30,000 for some that the government, through the agency of the NCB, dangled in front of their noses.

This vote against the area and local leadership was repeated in a majority of pits – militant and non-militant alike – throughout the coalfield, with only a handful of exceptions. Undoubtedly this hesitation reflected a certain bitterness or lack of trust that existed after the retreat on Lewis Merthyr in 1983. But it also reflected that the ground had not been fully prepared amongst the miners by the traditionally Left leadership.

A recall area conference the next day (Sunday 11 March) again confirmed that South Wales would support the action but this time 17 lodges out of 45 voted against. A vote at a Scottish NUM conference on the same day saw a 50-50 split on whether or not to continue their action. Kent was 100% out by this time as was Yorkshire but the picture was still mixed in other parts of the British coalfield.

The Old Left area leadership in South Wales were jittery and did not have confidence about what would happen the following morning. In the end they left it in the hands of younger militants like Ian Isaac and Tyrone O’Sullivan. They held their nerve and organised pickets at all pits on the following morning to uphold the decision of the area conference. Even then there was fighting on some picket lines but by the end of that day most of South Wales came out and swelled the ranks of striking miners to over 100,000.

After that, lan Isaac remembers attending a meeting of the South Wales Area Executive where he and another left-winger argued, in the light of all pits and surface lodges now respecting picket lines after a shaky start, that “we should hold further mass meetings to vote on supporting those on strike and consolidate the mandate expressed by miners not crossing picket lines.

“This was argued against by a number of executive members including the president, Emlyn Williams, general secretary George Rees and vice-president Terry Thomas. They argued that it was too risky and what would happen if they voted against again? This was the expression of the kind of confidence that some leaders had in their members and this type of thinking would surface again over the arguments about a national ballot.”

However, the executive then agreed that Lodges could reconvene mass meetings to vote again on supporting the strike action of the Yorkshire miners.

In St John’s a recall Lodge meeting on 14 March reversed the previous vote with all but 30 of the 600 miners voting for all-out strike action against the pit closures after the miners had seen that Yorkshire was solid.

On Saturday 10 March there was a two to one vote against action at Blaengarw pit in the Garw Valley. Within days this had been transformed into a 300-80 vote in favour.

The national NUM leaders showed more determination and courage as the strike gained momentum but were clearly uncertain of the balance of forces at the start.

There was no doubt in anybody’s mind that this was going to be a more protracted and difficult struggle than the strikes of 1972 and 1974. But a leadership, as well as taking account of the true balance of forces in any situation, also has to give a lead when the battle lines are drawn.

Tyrone O’Sullivan, then secretary of Tower Lodge NUM in South Wales (who was later to become chairman of the Tower Colliery workers’ co-operative) told Militant early in the strike: “It’s not going to be easy but we can win”.5

Within a week over 80% of the miners were out on strike and134 pits were strikebound. But in Nottingham, the South Midlands and even the traditionally militant Northumberland area a majority of miners were still at work. This was to change over the coming days in Northumberland and Midlands but not in Nottingham.

In the Midlands and Staffordshire it was Militant supporters and other rank-and-file miners that worked to pull their pits out. Militant supporters played a crucial role at Littleton and Lea Hall pits. Combined with the efforts of pickets from other areas they managed to close 90% of the Midlands coalfield.

Undoubtedly, the forces that were to be ranged against the miners, which were apparent at least in outline before the strike started, were considerable. But such was the resistance of the miners, even despite its hesitant, chaotic start, that by the summer it was a strike that could have been won.

Within weeks a huge display of solidarity with mass meetings, rallies, concerts and fundraising for the miners had shot up. Particularly important to this was the establishment of the miners’ support groups and the women’s support groups.

However, even here the lack of a co-ordinated approach by the area and national leadership often led to a shambles about which groups of miners should be collecting in which areas; in particular the CP-influenced leaderships of areas were to play a negative role in this: a role which they were to extend during the strike to vendettas against other Lefts and any group of miners who threatened their ‘leadership’.

The hesitations at the start of the strike were a complicating factor in most areas of the country, even the traditionally militant ones. Although generally overcome, these were a big contributory part of the running sore that the issue of a national ballot and the situation in the Nottinghamshire coalfield became.

NOTES

1 Militant issue 685, 3 February 1984

2 Militant, issue 697

3 From The Enemy Within, Seumas Milne, Verso, London 1994, p16

4 For example in Maesteg 43 copies of Militant were sold in an hour. Similarly in other South Wales mining communities the following sales were noted: Resolven 44; Blackwood 35 and Newbridge 113 (the last two were in Neil Kinnock’s constituency)

Militant issue 691, 16 March 1984