SINCE THE start of the strike and for 20 years since, much agonised comment has been made on whether or not the strike would have been more successful if a national ballot had been called – either before the strike or within the first few months of strike action as the militant areas came out.

Right-wing critics, and some on the Left, argue that the NUM’s fundamental error was not calling a ballot, which undermined the whole basis of the strike and allowed the majority of miners in Nottingham to continue working. The NUM had a long tradition of democracy and balloting but it wasn’t always the case that ballots were held for industrial action. Particularly on the issue of pit closures, with some areas more affected than others, there was a tradition of spontaneous walk-outs and a genuine feeling that ‘secure’ areas like Nottingham shouldn’t be allowed to vote down strike action in other areas like Wales, Scotland and Yorkshire.

Tony Benn said on a television programme in July 2002 that even if there had been a successful national ballot it would have been overturned in Nottingham. Although possibly a section of Nottinghamshire miners may have ignored the strike call and crossed the picket lines, past experience would have suggested a majority could have backed the national union.

In the 1972 and 1974 strikes the Notts area voted against strike action on pay but still fully came out as part of the national strike. Henry Richardson, a left-winger opposed to pit closures, had been elected area secretary in January 1983. In 1984 Notts did have a ballot and 27% voted for strike action, still a minority, but only 19% had voted for action in the last ballot in 1983.

Even if there had been scabbing (strike-breaking), the numbers concerned would have been far fewer and, crucially, far less effective in terms of coal production used to undermine the solidarity and morale of striking miners and their supporters, if there had been a national ballot.

In the Midlands area, which had a hesitant start, the efforts of Militant miners had closed down 90% of the coalfield and a majority of Midlands miners were out for the duration of the strike. One test of miners’ opinion on the first weekend of the strike for ITV’s Weekend World showed that 62% supported the strike, 33% were against and 5% were don’t knows.1

During the strike Militant maintained a united stand with the miners and NUM and argued against the hypocrisy of the right wing in the unions over the ballot and the way they lined up with the Tories to try and undermine the strike.

But after the strike we pointed out that, because of the way the issue was used in the movement to cut across the miners’ struggle, a ballot should have been called, especially after the rule change at a special conference on 19 April, which allowed a 50%+1 majority for strike action (instead of the previous 55%+1). A ballot then, six weeks into the strike, would have seen a clear national mandate for strike action.

Striking Scottish miner Joe Owens commented ten years later: “Tactically, there should have been a ballot. It was a catastrophic mistake not to call one, particularly after the special conference… No one seriously doubts a majority would have voted to continue the strike, we were already dug in by that time. It would have won the Nottinghamshire miners over before a combination of time and resentment made that hope impossible. The impetus would have swung back to the NUM, its critics disarmed… By the end of April the question had become academic to the vast majority of miners on strike, who constituted the vast majority in the coalfield, yet it was an opportunity lost and it cost the union dearly.” 2

A Sunday Times Insight book produced shortly after the strike recalls opinion polls at the time that showed things were moving in the NUM leadership’s direction should they call a ballot. A 13 April Mori poll for the Sunday Times amongst all miners confirmed what earlier opinions polls had begun to show and it counted: “68% for, 26% against and 6% uncommitted [assuming that the don’t knows would have failed to vote]… that would have produced an almost unassailable 72% vote in favour. Even Nottingham, the most resolutely reluctant area, had by now apparently revised its view from outright opposition to a 42:43 dead heat in the area council.” (3)

Even given the fallibility of opinion polls, the NUM leadership giving a lead at this point could have produced a thumping majority for action which would have cut across the excuses of the right wing and Labour leader Kinnock. It could have cut off the Tory lifeline of coal supplies to the power stations from the Midlands, which was to prove crucial at a later stage of the strike. Despite this, the lack of a ballot in itself did not defeat the miners – although it was undoubtedly a complicating factor.

The main reason the miners lost was because key trade union leaders refused to organise effective solidarity action, where the lack of a ballot was used as a ‘get-out’ clause.

The right-wing leader of the electricians’ union Eric Hammond said after the strike that he would have supported bringing out power industry workers if the miners had held a ballot. Yet, this was a smokescreen to cover his inaction and later betrayal of the miners. He would have still done everything to prevent such action developing as was to be the case later on (see chapter 7).

The Achilles heel of federalism

THE FEDERAL structure of the NUM had its strengths and weaknesses. It had allowed the development of militant areas, such as South Wales from the early 20th century. Even the areas themselves were effectively federal structures. The South Wales miners were originally known as the Fed (as was the national union) and Yorkshire, although right wing for a long time, had eight area panels (later cut to four) where the Left developed and organised unofficial action.

This allowed localised area industrial action under Rule 41 where the union’s national executive had the power to endorse strike action in an area. This was how the strike developed in 1984. Rule 41 had been used sometimes by the Left to undermine right-wing attempts nationally to block action as area strikes spread to other areas through flying pickets, and miners refusing to cross picket lines.

But, conversely, it also could act as a brake on area and national action on key issues as well if miners from other areas refused to back those striking miners or tensions and friction arose – as was evidenced over Tymawr/Lewis Merthyr in 1983.

Traditionally, the union right wing use the call for ballots to delay or halt effective action. However, used effectively and prepared for by the Left, a successful and healthy ballot could have greatly enhanced the legitimacy of strike action as it did in 1972 and 1974.

There was a strong tradition in the NUM of individual pithead ballots and it was a respected means of addressing policy issues and legitimising disputes in the industry. Scargill and the Left either were not confident about getting a majority in any ballot or they thought the numbers on strike were sufficient in themselves and may have thought the chaotic way the strike was developing was a safer option.

The majority of miners were on strike. Less than 20% were at work at this stage and even less than that crossing picket lines as miners were not being allowed to mount pickets anywhere near the Nottingham coalfield after the Notts area ballot on 14 March 1984.

But for socialists and the best trade union activists, having a ballot to call or endorse action was not and is not an absolute principle – despite the anti-union laws. There are times where the momentum of action means having a ballot will be a backward step in organising the action.

For instance, in the postal workers’ action in 2003 it would have been irresponsible to argue for a national ballot – especially given it now takes weeks to organise and implement – when effective strike action was taking place and spreading.

Indeed, postal ballots in particular are used by the right wing and ruling classes generally to rely on an inert layer in the trade unions to vote against action. Such a layer are subjected to a barrage of drivel and reactionary TV and media propaganda while the counter-arguments would only come out in detail at union meetings, as the capitalist media would not allow union activists a fair crack of the whip in explaining their case.

Those who are most directly involved in the union branches, workplaces committees and on the picket lines are the ones who can counter such arguments and mobilise greater numbers behind industrial action.(4)

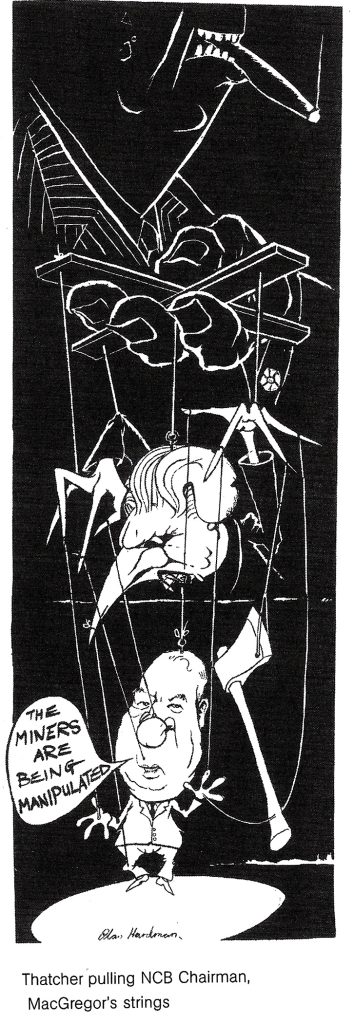

But, given that recent ballots had not returned such a majority for action, to put the strike on hold – as the right wing in the NUM argued – while a national ballot was organised would have been wrong. Indeed the momentum for the strike was developing, as MacGregor initially planned to cut coal production from 101.4 million tonnes to 97.4 million tonnes, which entailed the closure of 20 pits and the axing of 25,000 jobs. Within a week these plans had been upped to mean the closure of 35 pits.

Scotland and Yorkshire had by this time voted for an all-out strike. Votes in South Wales were turning round in solid support of the strike after the area director Philip Weekes announced that six of the remaining 23 collieries in South Wales were now subject to review for closure.(5)

Within a week, despite initial votes against coming out, all but three South Wales pits were out on strike – and these were soon to follow. All were signs that even a difficult, messy start could be successfully turned round.

In areas where ballots were organised – even without proper picketing taking place – there were positive signs that if a national ballot were to be held then it would return the required majority. In a Midlands ballot the result was still a vote against action, but there was 17% more in favour of action than in a ballot just a few months previously.

If this trend had been repeated evenly across the country then the result would have been a majority for national action.

Making the strike solid

ALTHOUGH A ballot was not the must urgent issue on the agenda at that stage – certainly not to sriking miners – it was increasingly clear that the Tories had deliberately provoked the strike and hoped to whip up confusion surrounding the strike by raising the call for a ballot in a media offensive.

Militant said at the time that the key issues were to make the strike solid amongst the miners and take the case to the wider working class. We argued amongst miners there was a need to link the issue of protecting jobs with a national pay claim, as pit closures did not affect all areas of the NUM equally across the country.

In the wider working class, we called for a clear lead from the NUM’s national leaders to consolidate the strike action and build a genuine Triple Alliance with the railworkers and steelworkers, and other workers whose jobs would also be affected. Such action was needed to stop the movement of all coal stocks and supplies.

The Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU) had called on its members from early on in the strike not to allow the delivery of coal stocks. But making such a call was one thing, delivering it effectively was another.

Despite the absence of a ballot, 134 pits were out in support of the action within a week. South Wales miners and those from other coalfields were getting a friendly response in Nottinghamshire amongst both miners who had come out on strike and those still working. Yet, Militant supporters realised that mass picketing of Notts pits would not be enough to bring them out. Indeed, on many occasions it was impossible for many miners to get to or participate on picket lines given the role of the police (see chapter 4).

Militant supporters argued at this time that there needed to be properly organised meetings to address non-striking miners in areas like Notts, as well as picketing. South Wales miners visited all Notts pits in 1983 over Lewis Merthyr and addressed canteen meetings before setting up pickets. Things generally happened the other way round in 1984 where pickets were set up first and then there were attempts to talk after.

We also argued that in these key areas there should be dispensation given to striking miners to go back down the pits – especially when police were not allowing even local miners to talk on the picket line to those going in to work – and discuss with those miners who had doubts to try and win them over.6

It is still likely that had there been a vote against action in Nottinghamshire, then the putative leaders of the scab Union of Democratic Miners (UDM – which emerged after the strike from the working miners’ committee set up by Thatcher’s ‘advisers’ David Hart and Tim Bell) would still have used this to argue for Notts opting out of strike action.

But a ballot at a pivotal stage in the strike – when the majority of miners were out on strike – could have seen 60%-70% or more in favour of action. It could have been used to convince a large section of Notts miners to come out and possibly prevented the development or effectiveness of groups like the working miners’ committee initiated by shadowy individuals like David Hart, Tim Bell and the infamous Silver Birch, Chris Butcher.(7)

The special conference

IT LOOKED to many as if the NUM leaders were preparing the way for a national ballot. A special national NUM conference was held in Sheffield on 19 April 1984. As well as receiving reports on the action around the coalfields, the conference took a decision to lower the threshold for action in a national ballot from 55% to 50%. Although a narrow window of opportunity for a ballot opened up here it never came.

It was correct of the NUM leaders not to be bounced into a ballot by the Tories, the reactionary press or by their allies in the Labour and trade union movement, who one-sidedly and sanctimoniously called for a ballot from the early days of the strike. These same people never called for a ballot about the use of the police and were quite happy to decide unilaterally without a ballot that the Tory ‘right to work’ was inapplicable to those workers who took action to defend their jobs.

The issue of whether or not a ballot was conducted was ultimately not responsible for the defeat of the strike. The working class, understanding the hypocrisy of the Tories, rallied in overwhelming numbers to support the miners, financially, industrially and practically helping to offset the almighty ruling class onslaught.

At each stage of the strike, Militant urged miners to adopt the strategy of appealing to the movement to put pressure on the tops of the unions to organise solidarity action. We also urged the NUM leaders and miners to call on the Left leaders in the unions to pursue a strategy independent of the right, such was the urgency of support needed for the miners.

How these tasks were approached during the strike was to become the crucial issue that ultimately all the Left leaders, unfortunately including Scargill, did not successfully measure up to.

NOTES

1 Strike, 358 days that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight team, 1985, p57

2 Joe Owens, Miners 1984-94, A Decade of endurance, Polygon, Edinburgh 1994, p7

3 Strike, 358 that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight team, Coronet 1985, p78

4 A ballot could have been called while workers were on strike – not just at work – and the union could have organised meetings away from management pressure at the pits in Nottingham – possibly organising transport etc – and allowing strikers to mix with non-strikers and persuade them of the case for action.

5 St John’s, led by Militant supporters, was one of the six. It eventually closed in December 1985, two years later than the Coal Board had originally planned. The Lodge leadership and members continued to fight against the colliery closing for nine months after the strike and were seen as a model of resistance to closure at that time; conducting an independent public inquiry which proved that the pit was being closed for political reasons and not for uneconomic or geological reasons.

6 Militant, issue 692, 23 March 1984

7 Silver Birch was the nickname the media gave to Butcher as he travelled from coalfield to coalfield trying to organise strikebreaking activities.